views

New Delhi: A year ago a seemingly unstoppable global juggernaut, the once-confident India is now reeling from a perfect storm of a corporate IT scandal, the Mumbai attacks and economic slowdown.

Suddenly the talk is not of easy returns, unending high growth, or "India arrives". The chatter is increasingly of risk.

"All these events have added to a sense of more risk in India," said V. Ravichandar, managing director of Feedback Consulting in Bangalore, which advises multinationals on investments in India. "There is a squirrel attitude. The winter could be long and cold."

Satyam Computer Chairman Ramalinga Raju quit on Wednesday in India's biggest corporate scandal in memory, after revealing profits had been falsely inflated for years.

It has been called India's "Enron", raising suspicion there could be other skeletons in the closet of India's corporate boom.

It all came at the wrong moment for India, a combination of problems that punched a hole in the self-confidence — some say cockiness — of executives, politicians and middle-classes.

Only in 2007, India wallowed in success. Tata Steel made a $13 billion bid for Corus, the country's biggest foreign buy. A trillion-dollar economy grew at nearly 9 per cent. India won its first major international cricket cup in 25 years.

Many people are still bullish about India in the long term. But these new insecurities may impact on the economy, where there are signs investors are reeling back from ambitious plans, to politics, where growing insecurity among voters could add to the unpredictability of general elections due by early May.

Take politics. The Congress-led coalition government is battling the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party. The insecurity bodes badly for Congress in its hopes to retain power. But that insecurity could push voters to a "third front", smaller regional parties with charismatic but controversial leaders — like "Queen of Dalits" Mayawati — that send shivers down many investors.

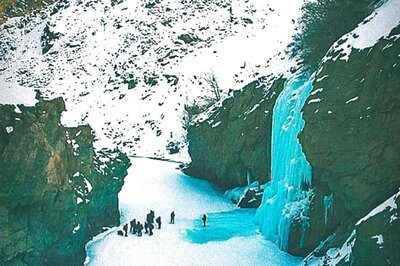

"Anyone in power in India has to be worried," said political analyst Mahesh Rangarajan. "Indians walk on very thin ice. There is no social security, job security. A third force may be able to take advantage of this insecurity.”

The decision of Tata Motors to pull out of West Bengal state in October after farmer protests against a factory for its low cost Nano, billed the world's cheapest car, also shocked India.

For all of India's optimism, it was a reminder that the country of sprouting shopping malls still must deal with the more than two-thirds of Indians who live on less than a dollar a day.

PAGE_BREAK

Hitting At India's Heart

The attacks in Mumbai that killed 179 people in November hit at the heart of India's growth story — many wealthy hotel guests from politicians to foreign investors that had long touted India.

And if anyone wanted a sign of a dip in middle class confidence, look no further than car sales, which dropped by nearly a fifth in November, the worst fall in eight years.

"That aggressive Indian feeling that 'we are there' has gone," said Rangarajan.

Now the data is increasingly scary. Industrial output fell for the first time in 13 years in October. After a six-year bull run, stocks fell more than 50 per cent in 2008, its worst slump ever, and 17 IPOs worth more than $10 billion were withdrawn in 2008, Thomson Reuters data showed.

"Once rosy, the same project is now seen as risky," said Saumitra Chaudhuri, a member of the Prime Minister's Economic Advisory Council. "People don't want to seize the opportunity as much as before. It was much easier to raise money last year."

Foreign investors are also cautious. Many executives, already having trouble amid a credit crunch persuading their CEOs to invest in India, have postponed meetings since Mumbai attacks.

Other Indians are waiting for the first quarter to see if hotels get packed, the norm during one of the most popular times to do business in India because of the temperate climate.

For some, the risks are creeping up. "India's low-cost advantage is well preserved at this time. It's still an attractive investment destination," said Bundeep Singh Rangar, chairman of IndusView Advisors, an India-focused M&A firm based in London.

"But no matter how great the cost advantage is, if safety and reputation are suspect, then that's not good. We've also got a critical election coming up, and often political goals don't match economic goals."

"You've got a downturn, terrorism and scandal... Yes, the growth, even at 7 per cent, is still attractive, but do you want to go into a market that has all these other issues?"

That said, many investors see India rebounding.

"Many have realised that India is not an island," said Russell Parera, CEO of KPMG consultancy in India. "But the underlying fundamentals are still attractive."

Comments

0 comment