views

Learning the Basics of Time Signatures

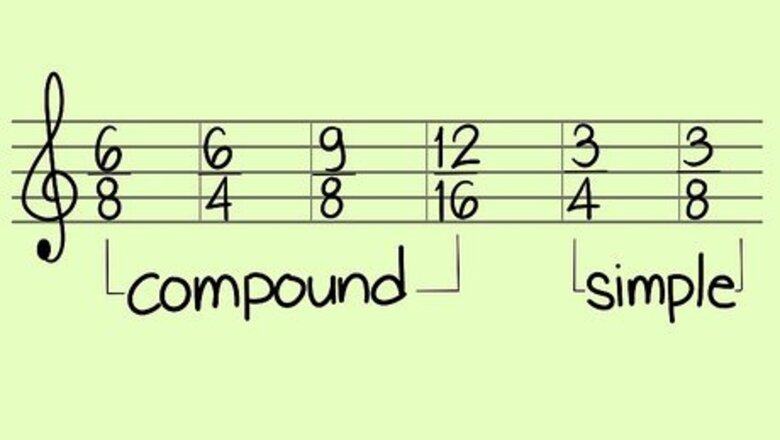

Distinguish between simple and compound time signatures. Find the time signature at the beginning of the song, just after the treble or base clef. A simple time signature means a regular note (not a dotted one) gets the beat, such as a quarter note, half note, or whole note. In a compound time signature, dotted notes get the beat, such as a dotted quarter note, dotted half note, and so on. The main way to identify a compound meter is to look at the upper number. For a compound meter, it must be 6 or higher and a multiple of 3. Following the rule of compound meters, 6/4 is a compound meter because there's a "6" on top, which is multiple of 3. 3/8, however, is a simple meter because the top number is less than 6. Time signatures are also referred to as meter signatures, and the time signatures tell you the meter for the song. When looking at the top number, it tells you the type of meter of the song: 2 = simple double, 3 = simple triple, 4 = simple quadruple, 6 = compound double, 8 = compound triple, and 12 = compound quadruple.

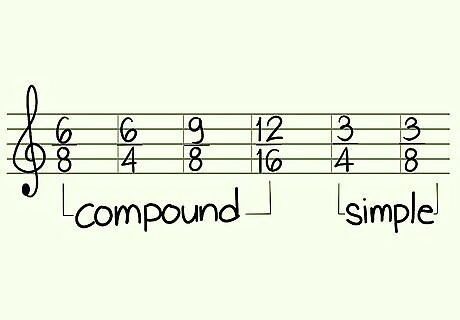

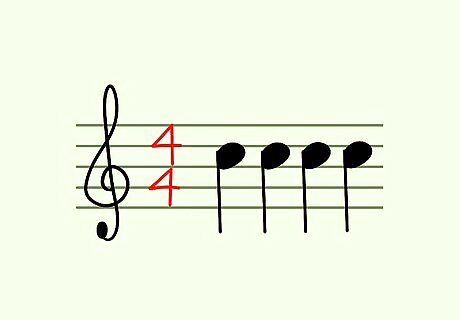

Identify what note gets the beat in a simple time signature by looking at the bottom number. The bottom number in a simple time signature tells you which note gets the beat. For instance, "4" indicates the quarter note gets the beat, while "2" indicates a half note gets the beat. The bottom numbers in a simple time signature always refer to a specific note getting a single beat: A "1" on the bottom tells you the whole note gets the beat. "2" means the half note is equal to 1 beat. "4" shows you the quarter note has the beat. When you see an "8," that means the eighth note lasts 1 beat. Finally, a "sixteen" tells you the sixteenth note gets the beat. For instance, 4/4 time is a simple time signature. The "4" on the bottom tells you the quarter note gets the beat.

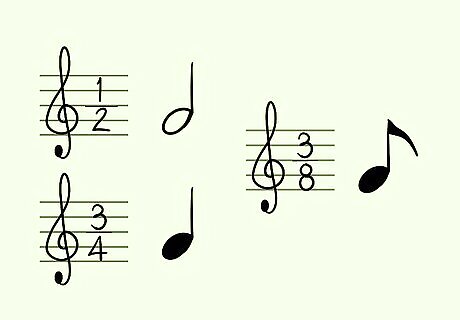

Figure out which dotted note gets the beat in compound time signatures. In compound meters, it's a little more complicated, as you could describe it 2 ways. A dotted note always gets the beat, but you can also look at it as a division of a dotted note, divided into 3 shorter notes of equal length. For instance, each of these bottom numbers tells you the following in a compound meter: A "4" means the dotted half note gets the beat, which can be divided into 3 quarter notes. "8" tells you the dotted quarter note gets the beat, which is equal to 3 eighth notes. A "16" shows you the dotted eighth note has the beat, equal to 3 sixteenth notes. 6/8 time is a compound time signature. The "8" tells you a dotted quarter note gets the beat; however, you could also say that a single beat is composed of 3 eighth notes (the same length as a dotted quarter note).

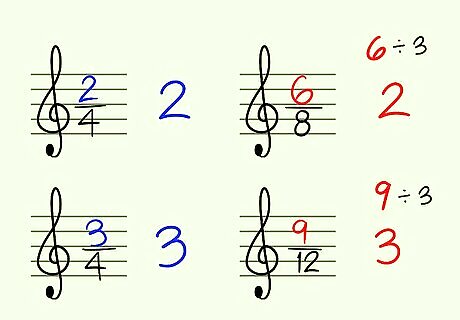

Figure out how many beats are in a measure. The top number tells you how many beats each measure gets. In simple meters, just read the number to get the beats per measure. In compound meters, divide the number by 3 to get the beats per measure. For instance, 2/4 has 2 beats per measure, and 3/4 has 3 beats per measure; both are simple meters. With compound meters, 6/8 has 2 beats per measure, while 9/12 has 3 beats per measure.

Learn the basic note values. When discussing note values, you generally assume 4/4 time because that is the most common time signature. In that case, the quarter note is the one that's filled in with a stem, and it gets 1 beat. Half notes are 2 beats and are hollow with a stem, while whole notes are just a hollow circle equal to 4 beats. Eighth notes are half a beat, and they have a filled in circle with a little flag at the top right of the stem, though sometimes they are connected to each other at the top. Rests also get beats, the same as their note equivalents. A quarter rest almost looks like a stylized 3, while a half rest is a little rectangle on top of the middle line. A whole rest is a little rectangle below the second line from the top, and an eighth rest is a stem with a little flag to the left at the top.

Figuring out a Time Signature by Looking at the Music

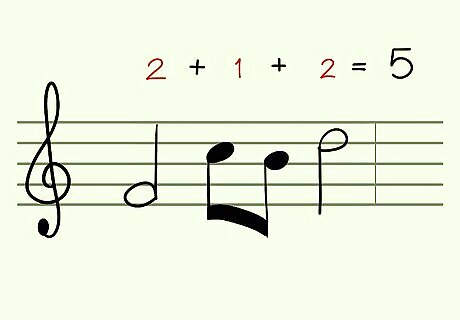

Work out the number of beats in the measure. When looking at a piece of music, you'll see 5 lines running parallel to each other across the sheet. In those lines, you'll see vertical lines that divide the music into measures. One measure is the space between 2 vertical lines. To find the beats in a measure, count the notes using a quarter note as the basic beat. Write the number of beats each note gets above the beat, then add them all together for the measure. For instance, if you have 1 quarter note, a half note, and a quarter rest, you have 4 beats because the quarter note is 1 beat, the half note is 2 beats, and the quarter rest is 1 beat. If you have 4 eighth notes, 2 quarter notes, and a whole note, you have 8 beats. The 4 eighth notes equal 2 beats, while the 2 quarter notes equal 2 beats and the whole note is 4 beats. If you have 2 half notes and 2 eighth notes, that's 5 beats as each half note equals 2 beats and the 2 eighth notes equal 1 beat.

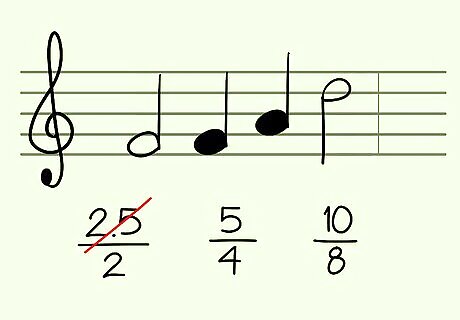

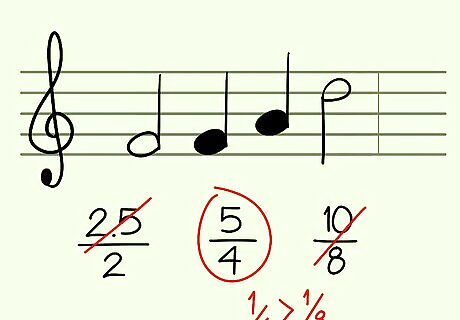

Look at the length of the notes to decide which time signature seems best. For instance, if most of the notes are quarter notes and half notes, it may make sense to have the quarter note take the beat. If more are eighth notes, it may make sense to have the eighth note take the beat. Basically, you want to make it as easy as possible when you're counting the beat, and therefore, the notes the appear the most should take the beat. For example, if the notes are 2 quarter notes, a half note, and a half rest, the time signature could be 6/4 or 12/8. In 6/4, the quarter note would get the beat; in 12/8, the dotted half note would, but you typically see more eighth notes in that time signature as 1 beat is equal to 3 eighth notes. In this case, 6/4 likely makes more sense. If the notes are 2 half notes and 2 quarter notes, that could be 2.5/2, 5/4, or 10/8. You shouldn't use decimals, so 2.5/2 is out. 10/8 doesn't make a lot of sense because you don't have any eighth notes, so 5/4 is the most likely, where you're counting quarter notes as 1 beat.

Aim for the longest note value possible when counting the beats. Typically, when deciding on a time signature, try to count the longest note value as the base beat, meaning which note gets the beat. For instance, count half notes as the beat if you can, but if that doesn't make sense, move on to counting quarter notes as the beat. In the example of 2 half notes and 2 quarter notes, 2.5/2 would count the half note as the beat, but since no decimals are allowed, choose the next longest beat, which would be the quarter note.

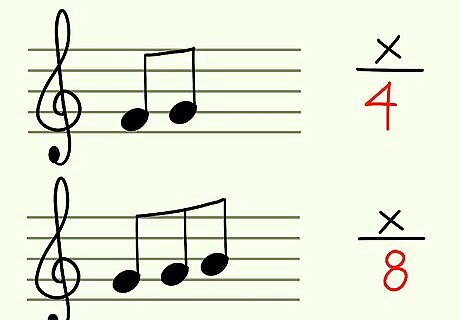

Examine how the eighth notes are grouped to help decide between "4" and "8." When the bottom number of the signature is 4, the eighth notes are often grouped by 2s, connected at the top with their flags. On the other hand, if the eighth notes are in groups of 3s, that usually means the bottom number of the time signature is 8 instead.

Hearing a Time Signature

Start by finding the main pulse or beat. When you're listening to a song, you may start tapping your foot or nodding your head to the beat. This beat is referred to as the pulse, what you count to when playing the song. Start by just finding this beat and tapping along with it.

See if you can hear an emphasis on certain beats from the percussion. Often, the even beats are given an extra thump or sound, particularly in rock or pop music. So for instance, you may be hearing "thump, thump, thump, thump" as the beat, but then on top of that, you hear an extra bit on some beats, such as "pa-thump, thump, pa-thump, thump. Many times, the first beat in the measure will be given a stronger emphasis, so try to listen for that, as well.

Listen for the backbeats to have an emphasis from other instruments. Even though the drums will often hit the even beats, other instruments in the song may hit the backbeats or the odd beats. So while you may hear a more solid thudding on the even beats, listen for the other beats to have emphasis elsewhere.

Check for major changes on the first beat of the measure. For instance, you may hear chord changes on the first beat of most measures. Alternatively, you may hear other changes, like melody movement or harmony changes. Often, the first note of the measure is where major changes in the song happen. It can help to listen for strong and weak notes. For instance, the beats for duple time (2/4 and 6/8), are strong-weak. The beats for triple time (3/4 and 9/8), are strong-weak-weak, while for quadruple time (4/4 or 'C' for common time and 12/8), they're strong-weak-medium-weak.

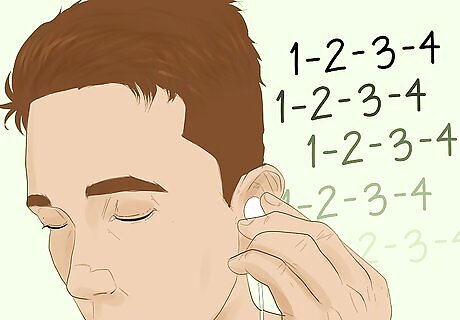

Try to hear how the beats are grouped based on the cues. For instance, you may notice beats are grouped in 2s, 3s, or 4s. Count the beats out if you can. Listen for the first beat in each measure, then count out the notes, 1-2-3-4, 1-2-3, etc., until you hear the first beat of the next measure.

Choose the most likely time signature for the song. If you are hearing 4 strong beats in a measure, you likely have a 4/4 time signature as that's the most common in pop, rock, and other popular music. Remember, the bottom "4" tells you the quarter note gets the beat, and the top "4" tells you that you have 4 beats in each measure. If you feel 2 strong beats but also hear notes in triples behind it, you might have a 6/8 time, which is counted in 2s but each one of those beats can be divided into 3 eighth notes. 2/4 time is most often used in polkas and marches. You may hear "om-pa-pa, om-pa-pa" in this type of song, where the "om" is a quarter note on the first beat and the "pa-pa" is 2 eighth notes on the second beat. Another possibility is 3/4, which is often used in waltzes and minuets. Here, you'll hear 3 beats in the measure, but you won't hear the triplets you do in 6/8 (a triplet is 3 eighth notes). Dance music is almost as big a category as non-dance music. In terms of time signature, you can use the music to which it is easy to dance, has a predictable section length, and about 16 bars. Plenty of modern electronic dance music has a pretty clear drop. So the song with the highest energy and biggest bass drops is suitable for dance.

Comments

0 comment