views

X

Research source

That is why it's so important to write a closing argument that is memorable, factual, and informative.

Preparing to Write a Closing Argument

Take notes throughout the trial. Unlike an opening argument, which can be written well in advance of the trial, a closing argument will be based on the events of the trial. Attorneys usually do not prepare them until both sides of the case have rested. With little time to construct an impactful closing, having good notes about the case is important. Be sure that you have notes about damaging testimony that you were presented with during the trial. This will give you the opportunity to reference that evidence in your closing argument.

Write an outline. An outline for the closing argument will serve as a script, or a guide to follow while speaking to the jury. This will help you feel more organized, and will minimize the risk of forgetting key facts. Use a legal pad to write down all of the major points that need to be made, and then fill in the outline with details and specifics that support your theory of the case. For instance, in a murder case, important details that both sides may want to talk about include the physical evidence that may link the defendant to the murder, whether or not the defendant has an alibi, any problems with the murder investigation, and any motive the defendant may have had to commit the murder.

Prepare visual aids. After sitting through a trial, many jurors have heard and seen a huge amount of information. To help the jurors remember the information that was presented throughout the trial, and to make sure that the jurors remember the important parts of your closing argument when they begin deliberations, use visual aids during your closing argument. Charts, graphs, pictures, and words can be used as visuals during your closing argument. Such visual aids are quite common in personal injury cases. For example, if you are the prosecutor during a murder trial, use a picture of the victim when he or she was still alive, a timeline of the defendant's movements around the time of the murder or a word that represents your theory of the case (such as jealousy or greed). To ensure that you use visuals aids effectively, choose one or two that you can use throughout the trial, and make sure that whatever visual you use is easily understood by the jury. To use a visual aid during your closing argument you may need to get approval from the judge. You must get permission from the judge to show pictures or other types of visual aids that were not admitted into evidence during the trial. However, if the visual aid that you plan to use in your closing argument is an exhibit that was admitted into evidence during the trial, you can use it without approval.

Remember to use simple language while writing your closing. To make sure that everyone in the jury understands your closing argument, also avoid technical or legal terms. The average juror has a sixth grade education, so don't alienate people by trying to sound “lawyerly” or “smart.” Instead, try to connect with the jury using simple words and ideas that everyone will be able to understand.

Reviewing Your Case

Repeat your theory of the crime. During the opening statements, you or another lawyer on your side should have offered a theory of the case. This theory could include an explanation, motive or defense to the crime committed, depending on which side is being represented. Bring that theory to the jury again, and remind them that it was established at the beginning of the trial. The theory of the case is essentially each side's version of what happened, and if the juror's believe one side's theory, that side wins. Because the theory of the case stays the same throughout the trial, the jury should be familiar with each side's theory of the case when closing arguments are given. Bring up your theory at the beginning of your closing argument. Try to bring it up during the first 30 seconds of your argument to focus the jury's attention on the theory. Then continue to reference the theory throughout the rest of the argument. Be sure to use active, descriptive language and strong transitions between ideas. This will help capture the jury's attention and help them sympathize with your client.

Review your evidence. Remind the jury of the facts you promised to prove to them during the opening statement, and take them step-by-step through the facts of the case from your side's perspective. Include expert testimony, witness testimony and physical or forensic evidence that supports your theory. Point to the promises that have been fulfilled and the ideas proven from the opening statement. The prosecution and the defense will necessarily have different views of the facts, so make sure that whichever side you are on, you tell the jury the facts in a way that is favorable to you.

Use well known stories, analogies, and rhymes to prove your point. During your closing, you can use analogies and stories to explain your theory of the case. If you do choose a story that you think fits the case, make sure that it is something that most people would have heard of so you don't have jurors who have no idea what you are talking about. For example, making an analogy between a murder case and the Cain and Abel story in the Bible may work if the facts are similar because many people have heard the story. On the other hand, analogizing a jealous murder to Shakespeare's Othello will probably not help the jury understand your case, because not too many people read Shakespeare. You may also use rhymes and phrases to drive home your argument to the jury. For example, during the famous O.J. Simpson trial, the defense attorney coined the phrase “if the glove doesn't fit you must acquit” to make sure that the jury would not forget an important piece of evidence: the glove.

Get the jury on your client's side. Ultimately, one of the most important things you can do is to get the jury to sympathize with your client. Try to paint your client in the most favorable light possible and elicit sympathy from the jurors.

Attacking the Opposition's Case

Listen to the other side's case during the trial. You should stay engaged, even when you are not speaking yourself. Listen attentively and take notes, identifying any weaknesses in the opposition's case. You can find weaknesses in your opponent's case by focusing on: Things that they say or that their witnesses testify to that are not supported by evidence, or Things that they say or their witnesses testify to that you can refute with your own evidence.

Point out discrepancies in the other side's theory. Challenge the overall position, as well as the other side's specific witnesses, evidence, and experts. Highlight inconsistencies to discredit anything the other side tried to prove or defend. For example, you could point out that your opponent is paying their expert witness to testify, and therefore that testimony is not as credible because it is essentially exchanged for money. You could also point out that other witnesses may have a stake in the outcome of the case. For instance, if a defendant's mother testifies that he was with her at the time the crime was committed, you could point out that as his mother she does not want him to go to jail, and therefore she could be lying. It is also likely that a witness on the other side made some sort of inadvertent comment during testimony that is not helpful, and may even be harmful, to the other side's case. Point this out during your closing. However, in a criminal case, you may not make any comments about the defendant choosing not to testify in his own defense. Such comments violate the fifth amendment prohibition against self-incrimination, and making statements such as “he didn't testify because he's guilty” and similar ones is grounds for a mistrial.

Remember that the prosecution bears the burden of proof. A defendant is presumed innocent until proven guilty, so the prosecution must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant committed the crime. Therefore, if you are the prosecution, you should focus on making the evidence seem impenetrable. If you are the defense, you may want to point out any weaknesses in the evidence, trying to demonstrate that the prosecution did not meet the burden of proof.

Concluding Your Closing Arguments

Conclude with emotion. Once you have finished reviewing the story as your side sees it, appeal to the emotions of the jury. You can appeal to the jury members as members of the community or as the people that have the power to dispense justice. However, make sure that you do not argue improperly by appealing to the jurors prejudices against a certain group of people. For example, it is improper to make an argument for a high award of damages based on the wealth of the individual or corporation that is being sued. It is additionally improper to ask the jury to base their verdict on characteristics of the defendant or victim such as race or sex.

Make your final statements memorable. Your final words should stick with the jury as they begin to deliberate. Ending on a strong, memorable message can keep your words and ideas resonating in the jurors' minds. Some examples include talking about a juror's duty to uphold the law and dispense justice, or talking about how letting a defendant go free would put him or her back on the streets to commit more crimes. For instance, the prosecutor could say to the jury that “the verdict in this case does more than decide just this case. The verdict is a message to the community that you will not tolerate crime and those who commit crimes.”

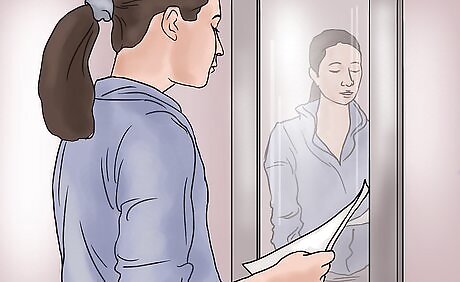

Practice the closing argument. Use colleagues, friends, or even a mirror to practice your final speech. Practice will make sure that the presentation is natural and comfortable, and that you follow your outline. Additionally, saying something aloud can help you determine whether it sounds natural. If you have an audience, ask them what part(s) of your closing stuck with them to be sure that you are emphasizing the appropriate points.

Comport yourself appropriately in the courtroom. Though they shouldn't matter as much as your argument, the impressions that you make on people do make a difference. As such, you should dress well, be well-groomed, keep a conversational tone, and make sure you come across as trustworthy and confident.

Comments

0 comment