views

What are microaggressions?

Microaggressions are indirect, subtle, or unintentional discriminations against members of a marginalized group. Microaggressions are indirect, subtle, or unintentional discrimination against members of a marginalized group. Microaggressions are verbal or nonverbal insults that target a person’s ethnicity, country of origin, race, age, gender, sexuality, disability status, religious affiliation, or economic status. Many people who commit microaggressions don’t mean to cause any harm. But their impact can be devastating, especially over time. The term “microaggression” was first used around 1970 by Harvard psychiatrist Dr. Chester Pierce. Dr. Pierce used the word to describe the frequent insults and unconscious bias spread by non-Black people against Black people. Examples of microaggressions include: Telling a non-white person or someone from another country, “You speak good English.” This implies that people like them don’t ordinarily speak intelligently or fluently. Avoiding a Black person’s gaze, implying they are dangerous and it’s unsafe to make eye contact. Telling a woman, “You should smile more.” This implies women’s value lies in their appearances. It also implies that it is undesirable for a woman to experience an emotion other than happiness Telling a disabled person, “You’re so brave.” This implies there’s something unusual or wrong with how they experience the world Commenting that an unhoused person is probably living on the streets because they’re a drug addict. This implies that it’s their fault that they’re homeless (and also implies that people with a substance use disorder don’t deserve rights) Telling a trans man, “I also wanted to be a boy as a child.” This implies they’re simply going through a phase and should grow out of it

The 3 Types of Microaggression

Microinvalidations The most common form of microaggressions are microinvalidations. These are comments that dismiss or deny a person’s own lived experience. These comments may not be explicitly insulting. But they imply insulting opinions about the victim’s character or worth based on their marginalized status. Examples include: Being condescending to a woman by calling her “sweetheart.” Invalidating a person of color’s experience of racism by insisting that “We’re all part of the same race—the human race.” Negating the experience of someone from a disenfranchised background by saying, “Anyone can succeed if they put in the work.”

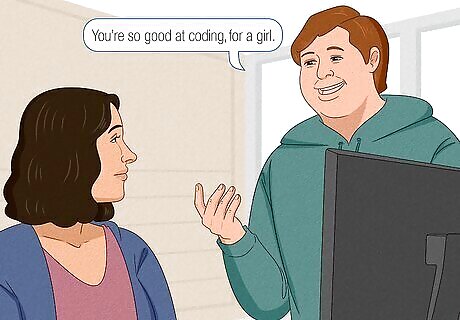

Microinsults Microinsults are indirect insults—often unintentional—directed against others based on their marginalized status. Microinsults are also often not explicitly insulting. But they imply resentful or threatened feelings toward a person based on their marginalized status. Examples include: Suggesting someone got their job because of affirmative action. This implies that they don't have the necessary skills, talent, or qualifications for the role. Telling a woman, “You’re so good at coding for a girl.” This suggests women are not generally expected to excel in certain areas of work. Assuming a person is unintelligent based on the color of their skin, their socioeconomic background, or where they live

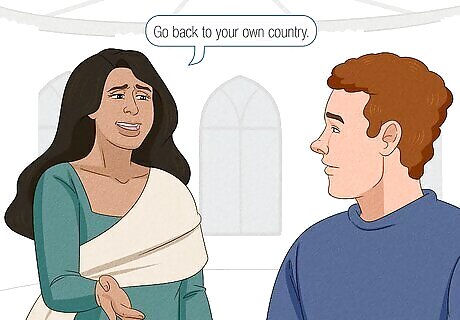

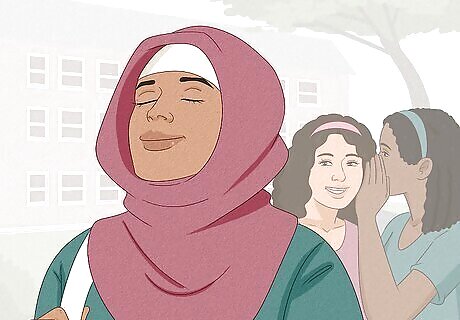

Microassaults Microassaults are deliberate slights and insults committed with the intention of hurting someone based on their marginalized status. It is possible that the aggressor may not fully understand just how harmful these assaults can be. This may include name-calling, jokes, avoidant behavior, and intentionally discriminatory behavior. Examples include: Not promoting a woman based on her gender Crossing the street or going inside when a person wearing a taqiyah or hijab walks by Saying “foreigners” are taking everyone’s jobs Telling someone to “go back to their own country”

What impact do microaggressions have?

Microaggressions can negatively affect the victim’s health over time. Many people who experience microaggressions experience them often. Microaggressions have been referred to as “death by a thousand cuts.” Microaggressions can lead to the following consequences over time: Racial trauma, or race-based traumatic stress (RBTS), (the mental and emotional harm caused by racial bias, ethnic discrimination, racism, and hate crimes) Depression, stress, and anxiety Fatigue and decreased motivation Low self-esteem and feelings of being a "second-class" citizen Mistrust of others Traumatic reminders of past historic injustices. Examples of this are the enslavement of Black people or the incarceration of Japanese Americans during WWII

Microaggressions can limit the victim’s professional opportunities. Microaggressions and unconscious bias can lead to discrimination in the workplace, even unconsciously. Unconscious bias towards white, straight, able-bodied, cisgender men leaves people who don’t fall into these categories behind. Moreover, constant microaggressions can strip a victim of their motivation to work hard or their belief in their abilities to succeed professionally. In a 2023 study, the majority of immigrants to the U.S. reported experiencing workplace discrimination. Most of that discrimination being targeted at non-white immigrants.

Microaggressions can promote an intolerant, discriminatory culture. The more unconscious bias goes unchecked, the more common it will become.

How to React to a Microaggression

Pause to consider how you’ll respond. Take a deep breath and consider how you want to respond. After you've had a moment to think, you may realize that you do want to confront the microaggressor in the moment. You may also decide you’d rather let it go for now, and either bring it up later or not.

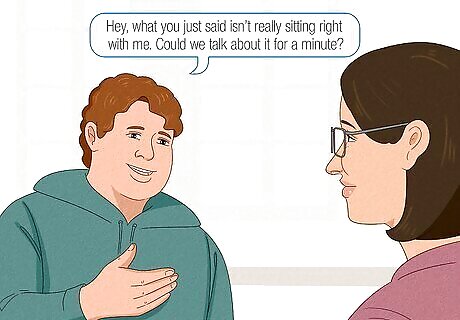

Ask the person if you can talk about it, if you want to address the issue. If you decide you’d like to confront the person, see if they’re open to discussing the issue. Many people will be open to talking when invited calmly. While the comments made can be incredibly triggering and upsetting, attempt to channel those feelings of hurt into a productive conversation where you can convey the impact they have on you. For example, you might say, “Hey, what you just said isn’t really sitting right with me. Could we talk about it for a minute?”

Describe what was said or done to check your own assumptions. Before confronting them about their behavior, make sure you didn’t mishear or misunderstand what they said, especially if this sort of behavior is out of character for this person. It’s also possible the person doesn’t realize what they have said or done is offensive. But this doesn’t diminish the impact of their actions. It can actually be harder to deal with an unconscious microaggression. If the aggressor means no harm, you may be left wondering if you're being overly sensitive or paranoid by taking offense to their actions. You might say, “Did I hear you correctly? It sounded like you said…” or “Could you repeat what you just said?”

Focus on the person’s behavior rather than who they are as a person. You may have your own opinions and assumptions about this person based on their background, political views, religion, etcetera. Try to separate these identifiers from the current situation Instead, focus only on what they have said or done. It’s helpful to stay focused on the matter at hand, but being openly critical of who they are as a person may make them feel attacked and less receptive to hearing your concerns. It’s tough to have empathy for someone who commits a microaggression against you. But try to consider how their behavior has been shaped by their experiences. What may lead them to act this way? How could their mind be changed? For example, instead of, “That’s not a surprising comment coming from someone like you,” you might instead say something like, “That comment was really harmful and makes me wonder where you got that idea.”

Invite them to share their perspective. Exploring their actions and the beliefs behind them can help you both to better understand why they behave as they do. It can also challenge their assumptions. Sometimes, people commit microaggressions because they lack self-awareness. For example, if they’ve told an offensive joke, you might ask, “Can you explain the punchline?” Making the invisible visible can force the aggressor to confront the impact of their actions. If they’ve made a stereotypical comment, ask them sincerely, “What leads you to think this?”

Explain the effect their behavior has. Guide them through your reaction to what they’ve said or done. Describe how their behavior made you feel and the effect it could have over time. Try to convey how their behavior wounds you and your relationship with them, and how it promotes marginalization and discrimination towards a certain group of people. Consider saying something like: “When you made that joke, I felt shocked. It made me feel dismissed and promotes racist stereotypes.” “I don’t know if you’re aware of the meaning of that word, but it’s actually really demeaning and offensive.” “Even if that comment was well-intended, it’s actually quite sexist, and over time comments like that create a work culture that isn’t supportive of women.”

Appeal to their values and sense of empathy. At the end of the day, most people don’t want to cause harm and don’t realize the impact their behavior can have on others. Appealing to the person's sense of right and wrong and their sense of compassion can help persuade them to reconsider their behavior. You might say something like, “I know you don’t want to promote harmful stereotypes,” or “I can tell you care about other people’s well-being, but that comment goes against that value.”

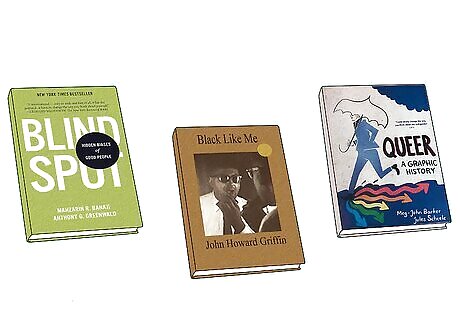

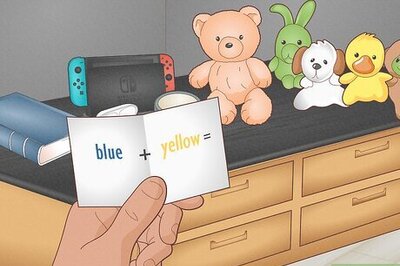

Connect them with educational resources, if you want. If you feel compelled, consider recommending books, podcasts, articles, websites, and more resources that can help educate them further about the topic and engage with new perspectives. For instance, you might recommend the book Blindspot: Hidden Biases of Good People by Mahzarin R. Banaji & Anthony G. Greenwald. Or, you could suggest that they check out Queer: A Graphic History by Dr. Meg-John Barker and Julia Scheele, Black Like Me by John Howard Griffin, or the Throughline podcast from NPR. Only do what you feel comfortable doing and what you have the time and energy to do. Remember that you are not personally responsible for putting in work to educate the aggressor. They are ultimately the only person who can control their behavior.

What to Consider When Deciding How to Respond

What is my connection to the aggressor? Your relationship with the aggressor may help you decide whether you want to confront them and how. If they’re in your friend group and you see one another often, it may be worth addressing the problem. But if they’re a stranger at the supermarket, it may not be worth your emotional energy. How much you trust the aggressor can impact your decision. For instance, if the aggressor is typically very difficult to get along with and resistant to criticism, you may not want to put yourself in the situation of feeling further attacked. It also may feel unsafe to do so. Alternatively, if they’re a trusted colleague whom you suspect doesn’t wish to cause harm, they may be receptive to a conversation.

What’s their experience with me and my background? Consider what may cause the aggressor to hold the perspective they do. What may have led them to behave the way they did? What experiences might they have had that could lead them to believe their behavior is acceptable? For example, if they’ve grown up in a particular culture or with a family that embraced harmful ideologies, they may have adopted the same ideologies.

What assumptions do I hold about them and the type of person they are? What beliefs do you currently hold about the aggressor and their background that may get in the way of a productive conversation? How can you extend compassion towards them? Their appearance, political views, associations with people you have conflict with, and many other characteristics may be factors in how you view this person. While some of your views may be accurate, try to recognize that real change is likely to come from engaging the aggressor with mercy. At the same time, you don’t need to engage with them at all.

What will the outcome of my response be? Before deciding how to act, think practically about what effect your response could have in the future. For instance, if the aggressor is someone you work with, consider how confronting them will affect your experience in the workplace. If they’re generally an open, well-intentioned person you can trust, talking to them may make the workplace more tolerant and harmonious. But if they’re generally stubborn and defensive, trying to hold them accountable for their actions could cause friction between you and make your work life more stressful. Ignoring the confrontation could make the workplace more peaceful. It can also negatively affect your own mental health and help to promote a discriminatory work culture. Remember that you never need to let things go to “keep the peace.” Rather, consider the effect confronting the aggressor will have on you and your peace. If you are in a workplace and feel uncomfortable addressing the person directly, know that it is your right to have a safe and non-discriminatory environment. Consider having a conversation with your company’s HR department or a trusted manager to inform them of the comments being made toward you.

What to Do If You've Committed a Microaggression

Pause for a moment. It can be tough to hear you may have said or done something that left someone else feeling uncomfortable, hurt, or unsafe. Your immediate reaction may be to go on the defense. Instead, pause for a few seconds, take a deep breath, and consider what they’re telling you with openness and curiosity.

Listen calmly. Even if you think, my intentions were good or even I’ve done nothing wrong, try to understand that the person confronting you feels differently. Take their concerns at face value. Although it can be uncomfortable, take time to listen and hear how your behavior may have come off to others - even if it was unintentional.

Believe the person. Your intentions were likely not to hurt somebody’s feelings or make anyone feel unsafe. But try to separate your intentions from the actual impact your behavior has had. Trust that the person confronting you may understand the implications of your behavior better than you.

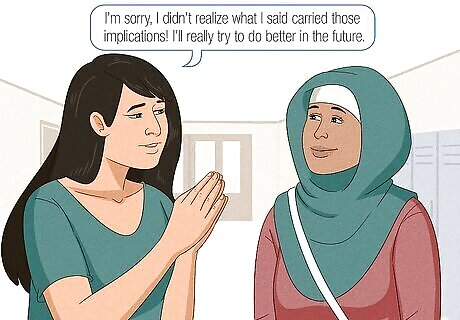

Own up to your behavior and apologize. It’s hard, but try to accept that you’ve messed up. Everyone makes mistakes, and the way to move forward is to take responsibility, apologize, and try not to make the same mistake again. Try not to dwell in guilt or shame—this is a learning experience! Ask the person for forgiveness, and then work to forgive yourself, too. Try saying something like: “I’m sorry, I didn’t realize what I said carried those implications! I’ll really try to do better in the future.” “Can you forgive me for messing up? I never wanted to hurt anyone, but I now see how my actions were harmful, and I really don’t want to make this mistake again.”

Consider asking them if they’d like to keep talking. If you feel comfortable with it, consider asking the person if they’d be open to talking more about the issue or if they have any resources they recommend, like books, websites, podcasts, or other people to talk to. They may be happy to keep talking, but they may prefer not to—respect their answer either way.

Talk to people you trust for their perspective. After an encounter like this, you may feel a little unsettled—that’s understandable! It can help to talk to a friend whose perspective and judgment you trust. Choose someone who will listen carefully and nonjudgmentally, but who will also offer their sincere thoughts on what happened.

Keep learning on your own. Whether you and the person continue speaking or not, and whether they offer you any educational resources or not, it’s important to keep doing the work on your own: challenge previous perspectives you may have had, consider influences on your beliefs over time, explore books, podcasts, articles, websites, and more that offer new and nuanced perspectives on the issue.

What to Remember as an Ally

Impact matters more than intent. You have likely heard someone argue that because they don’t mean to be offensive, what they say and do doesn't matter. But this isn’t true. Everyone makes mistakes. Some people will commit microaggressions without realizing the impact of their behavior. But insisting—even if it’s true—that the intent wasn’t to cause harm shifts the focus from the real issue at hand: that the aggressor’s behavior has, in fact, caused harm.

Believe your marginalized colleagues, friends, family, and acquaintances. If you’re not a member of a certain group, you can’t fully understand their experience. But you can try to empathize with them and trust that they know best when it comes to their own lived experience.

Be prepared to change your worldview. As an ally, you must always be open to learning and growing. This may mean being willing to change your mind about your beliefs. Remember that it’s not “weak” to change your opinion on something. Stay open and curious, read all you can about perspectives that differ from yours, and don’t cling too tightly to any of your own ideologies.

Accept you may be complicit. Allyship and complicity in discrimination are not mutually exclusive—in fact, they often go hand-in-hand. You may benefit from systems and institutions that privilege wealthy, white, straight, cisgender, able-bodied men, even if you don’t fall into all of these categories. You may have even committed microaggressions yourself without realizing it or intending to. The good news is that the more you educate yourself and stay open to feedback from the marginalized people in your life, the more you will become aware of how certain systems fail many people or are actively built to keep them down. You’ll learn how you can use your privilege to challenge those systems and beliefs.

Comments

0 comment