views

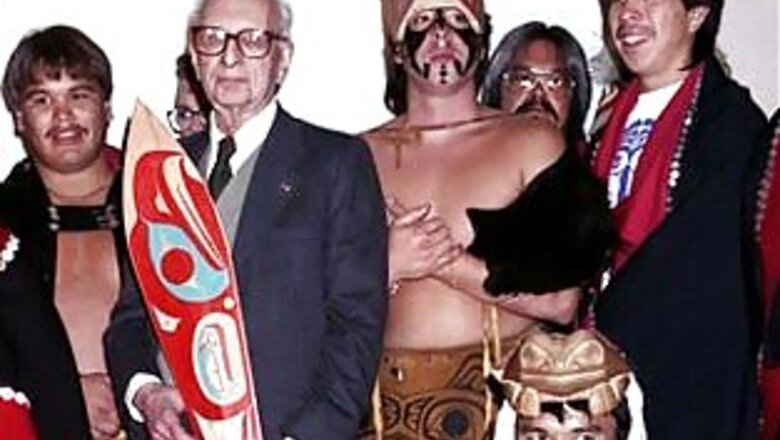

Paris: After weeks crossing the high seas, Claude Levi-Strauss breathed in his first lungful of the New World, a perfume tinged with pepper or tobacco. The sensory awakening was the start of a journey that turned a young Parisian scholar into a founder of modern anthropology.

On that 1930s trip that took him across the Atlantic to Latin America, Levi-Strauss' scholarly upbringing guided him on a methodical search for humankind's inner workings as he met tribes in Brazil's jungles. His studies would later electrify —and divide — the intellectual world with the idea that cultures share similarities underlying their myths and patterns of behavior.

Levi-Strauss' death at age 100 was announced in Paris on Tuesday. French media said he died on Friday.

Born on November 28, 1908, in Brussels, Belgium, to French parents of Jewish origin, he was forced to flee France during World War II after Germany invaded and the collaborationist Vichy regime passed anti-Jewish laws. He ended up in New York, which he called "the most fruitful period of my life."

He was widely regarded as having reshaped anthropology, becoming the leading advocate of what is now known as structuralism. His ideas reached into fields including the humanities and philosophy.

France reacted with emotional tributes led by President Nicolas Sarkozy, who called him the "indefatigable humanist" and noted his environmental side which led him to worry "about the disappearance of many living plant and animal species, and ... the impact of man's activities on the planet."

Koichiro Matsuura, director-general of the UN's Paris-based cultural arm, UNESCO, said Levi-Strauss' theories "changed the way people perceived each other, striking down such divisive concepts as race and opening the way for a new vision based on recognition of the common bond of humanity."

As a youngster, Levi-Strauss organised adventurous expeditions into the French countryside. He studied in Paris and went on to teach and travel in Brazil, captivated by that first impression of "tobacco smell, pepper smell" and doing much of the research that led to his breakthrough books.

Drafted into the French army only for it to be crushed by the invading Germans, he soon had to flee France for New York, where he became a visiting professor at the New School for Social Research. He mixed with fellow scholars, spent long hours at the New York Public Library and lived in a tiny rented room in Greenwich Village.

"Everything I know, I learned in the United States," he once said.

Despite several job offers to remain in America, he returned to France in 1944 after the liberation of Paris and entered government service, but quit four years later to pursue his scholarly research.

Structuralism, defined as the search for the underlying patterns of thought in all forms of human activity — compared the formal relationships among elements in any given system.

Levi-Strauss' classic example was the taboo on incest, present in all societies, which he argued was man's way of promoting and preserving social harmony.

Yet he rejected the title of "father" of structuralism, which he said had been badly deformed and its scientific claims exaggerated. He also spoke with modesty of his achievements.

But Setha Low, president of the American Anthropological Association, said Levi-Strauss was one of the most "innovative and creative theorists that anthropology has ever produced," though she said some of his theories are contested. One complaint is that he failed to sufficiently take into account history and the empowerment of individuals.

French anthropologist Philippe Descola, who wrote his thesis under Levi-Strauss' guidance, told AP last year that "today, nobody shares the entire philosophy of Levi-Strauss," but that his influence is still strong.

What was important, he said, was that Levi-Strauss advanced the idea that cultural diversity is a positive thing — an "idea that wasn't very popular" 40 years ago.

Honored by universities worldwide, accepted into the Academie Francaise, home of France's scholarly elite, Levi-Strauss was also a skilled handyman, loved music and believed in the virtues of manual labor and outdoor life.

He was married three times and had two sons, Matthieu and Laurent.

The Academie Francaise said it planned a ceremony of tribute for Thursday.

Comments

0 comment