views

Srinagar: The twin fuel stations at Srinagar’s MA Road reflect contrasting scenes. One is overwhelmingly crowded, while the other is shut. The vehicles are queued up over a kilometer, waiting to get tanks filled, resulting in a massive traffic jam on the city’s busiest road. The shut station had run out of fuel in the morning.

Less than two kilometres from the chaotic scenes, the Boulevard Road is unusually desolate. On a normal day, the road by the Dal Lake would be flocked by hundreds of tourists. The rows of shikaras are anchored. In the morning, most of the tourists had vacated houseboats and hotels on Dal Lake. In the interiors of the lake, famous for its floating market, an eerie silence reigned.

The government issued a frantic advisory on Friday evening, asking tourists to curtail their stay in Kashmir. The advisory sent the entire Valley into a state of panic. The situation was already uncertain following the mobilisation of tens of thousands of additional paramilitary troops. The frequent government orders unnerved the populace. People across the Valley rushed to markets to stock up on essentials.

Amid the pandemonium, a game of football at the nearby TRC Turf Ground is going on as usual. Nearly 500 fans, young and old, circle the Turf and enjoy the game with intrigue. A group of keen spectators, most of them in their 70s, reminisce of their “glorious past” when they used to play and watch alongside local greats like Farooq Dar and Habib Panzo.

“I have never seen a footballer like Dar in my entire life,” says 71-year-old Mohammad Hanif, who worked as a bus driver until recently. “I would hurry my commute, sometimes without passengers, from Anantnag to Srinagar just to watch Dar play.”

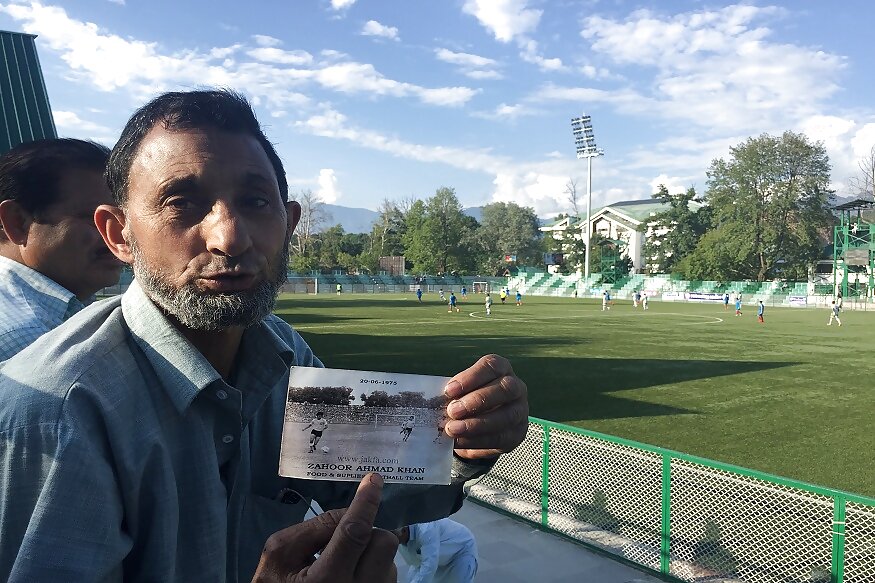

Hanif pulls out four black-and-white photographs from his waistcoat pocket. He shows the photos to his friends with pride. Everyone is keen for a glimpse. “I think this boy in the centre is Farooq Dar,” says Abdul Hameed. Nostalgia enveloped the group while looking at the photograph clicked in 1977.

There are trees in the back of the crowd in the photo and Nisar Ahmad says that he watched the match that day from the top of a tree.

The group seems oblivious to the chaos unfolding outside the stadium, on shop fronts, fuel stations and ATMs. Some of them drag heavy puffs of cigarette while cheering for boys sweating out in the field.

They have spent significant years of their youth watching football. But when insurgency broke out in the late 80s, everything came to a grinding halt. And football was no exception.

Hanif recalls an incident when he witnessed firing outside his home in Barbarshah locality of Srinagar. Those were the years when hundreds of boys took up militancy after crossing over to Pakistan-occupied Kashmir for arms training. Many of them were aspiring cricketers and footballers, including Hanif’s close friends. The firing incident shocked Hanif. “I stopped going out to watch football matches.”

By early 1990s, when the streets were resounding with gunshots, all sources of outdoor entertainment like cinema and sports had been put on the backburner. Kashmiris were dealing with more important issues.

But at the back of their mind, the group is conscious of the situation that has gripped Kashmir. While narrating how football came to a halt, Hanif is quick to draw parallels between 1990 and the current situation. “I hope these boys don’t have to face what we saw in our youth,” he says, his eyes fixed on the boys in the field. “I pray that politics does not affect the game.”

The floods of September 2014 destroyed whatever little sports infrastructure was in place. “The rebuilding process was long and daunting. But now we have astro turf (synthetic turf) with floodlights,” says Hanif.

In the past five years, professional football has made huge gains. Kashmir now has many clubs, including one that participates in I-league, the top football league in India. Srinagar hosted many I-league matches that saw jam-packed crowds even in the freezing winter. “For a moment, we thought we were back to our glorious days,” Hanif says.

But he is aware that when unrest breaks out, it engulfs everyone and everything. It pains Hanif to imagine the worse — their hard work of the last five years undone by conflict. “There should be a one-time solution to this trouble even if it takes an all-out war,” Hanif says.

The others in the group give approval to his utterances. “Bas jung hi kuch kar sakti hai,” Nisar says.

Soon, they slipped into discussion about various theories doing the rounds in Kashmir since last week. “This is a propaganda to scare us. Nothing is going to happen,” says Abdul Aziz Gojree, who sports a short white beard.

The others react quickly. “You don’t know. They have brought in hundreds of thousands of troopers,” Nisar says. “Something is going to happen on a large scale.”

The discussion turns intense and, for a moment, they forget about the game. They talk about who said what in Washington, Kabul, New Delhi, Srinagar and Islamabad, and try to guess what could be in the offing for Kashmir. “They could launch an attack on Pakistan,” Hanif speculates.

The game intensifies. All players close in on the goal post and for the first time, the ball enters the post. The group’s attention is diverted towards the field, but it turns out to be a self-goal. All of them burst into laughter amid shrieks and whistles.

They come to the stadium every day and watch the game till late evening. But today they are insisting that the manager cancel the match to be played under lights. “Due to the prevailing situation, we have to reach home early. Otherwise our families will scold us,” Hanif explains to the manager.

The other stands are dominated by young spectators. Some of them have come directly from their schools. Like the old group, they are also caught up in similar chats while enjoying the game.

In one corner of the stadium is a group of girls who are watching the game with similar fervour. They are all professional footballers.

Nadiya Nighat (22) from Natipora, an uptown Srinagar locality, is a professional football coach. She has been receiving frantic calls from the players of a Haryana team who are on their way to Srinagar. They are stuck at Jawahar tunnel, the gateway to the Kashmir Valley.

Since visitors have been asked to leave Kashmir, police stopped the team from entering the Valley. Nighat is calling her contacts to help her out.

“Sports and politics should not be mixed,” says Nighat, who is also enjoying the match played between the best teams of present times — J&K Bank and J&K Police.

She likens local football star Danish Farooq, who represents J&K Bank, to international football star Cristiano Ronaldo. Farooq played for I-league and is considered to be the best among the current lot.

Nighat avoids thinking about the situation outside. During the 2016 unrest, which lasted for six months, Nighat was restricted to the backyard of her home. “I would practise football in the backyard. It is hard to escape the situation.”

Comments

0 comment