views

The onset of summer in the Saurashtra region of Gujarat can be a frightening prospect. The rocky terrain of low hills and the semi-arid plains begin to radiate immense heat. Rivers and wells dry up in tandem. Water shortage looms large and the memory of the severe drought of 1999-2000 returns to haunt. God bless the man who tries to indulge in cultivation of crops in these parts.

But that’s exactly what hundreds of farmers do several times a year in the heart of this unfriendly terrain. Wheat, cotton, banana, papaya, sugarcane, tomatoes and a variety of other crops sprout all over, erasing forever the cliché of Saurashtra being a parched expanse.

Today, one can spot crops that weren’t grown in these parts just four or five years ago. In Adtala village, farmer Vallabhai Patel, who was previously cultivating cotton, grows papayas. With a limited supply of water, he got plentiful yield.

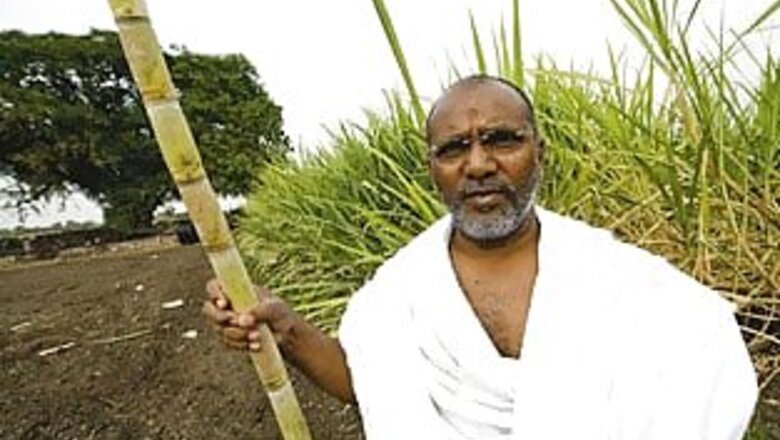

In Sarangpur, also in Saurashtra, Swami Arunibhagat is surely a God-blessed man. A leader of the liberal religious group, Swaminarayan Movement, he has converted 175 acres of dry land into a lush haven for sugarcane, tomatoes and genetically modified cotton. He has achieved record yields that have attracted farmers from more fertile lands to come and learn how he did it. It almost looks like a miracle wrought by Lord Hanuman of the famous temple in Sarangpur.

The swamiji is not alone. The entire region of Saurashtra, along with neighbouring Kutch, a half-desert, half-salty marsh region, has become the engine of a farming revolution in Gujarat, propelling the state into one of the fastest growing agricultural economies in the country. Gujarat’s agriculture has grown 9.6 percent per year in the last decade or so, surpassing the national growth rate of 2.9 percent and boosting rural incomes.

Agriculture in India has been condemned to an annual growth of 4 percent or less ever since the nation’s economic reforms pushed it towards a service-oriented economy. The share of agriculture in India’s gross domestic product (GDP) has fallen to just 16.6 percent from 46.3 percent about six decades ago. Somewhere, policymakers seemed to have ignored the importance of farming to the economy. But Gujarat hasn’t allowed its keenness to promote industry overshadow its farming sector.

“Although widely lauded for adopting an aggressive industrial policy that has made Gujarat a much-favoured destination for investment, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has actually devoted a great deal of energy and resources to accelerating agricultural growth in the state through a broad spectrum of policy initiatives,” say agricultural scientist Ashok Gulati and four others in an article published by the Economic and Political Weekly.

Studying the various points of attack that the state has used to revive agriculture could thus unveil important lessons for the whole country. After all, if the water-starved Saurashtra and Kutch could do it, why not the rest of India?

Fertile Policies

At first glance, the agricultural miracle in Gujarat seems to have been supported by factors such as good monsoon for most of the decade, increasing minimum support prices from the Centre and the spread of BT cotton, a lucrative cash crop. But all these benefits were available to other parts of the country as well and the superlative performance of Gujarat is not explained by them.

Gujarat was early to amend the laws governing the marketing of agricultural produce and allow farmers to sell their output directly to private buyers. Even today, many states haven’t done so and keep the farmer tied to the official procurement hubs. Some have gone back on reforms. But Gujarat has persisted with opening up market access to farmers.

This also opened up contract farming. In 2004-05, Gujarat took an unusual step. It allowed companies to buy crops from farmers a year in advance. This helped the farmers hedge against price upheavals and guaranteed a minimum price. What’s more, there is also some flexibility to allow higher payments if prices rose at the time of transaction. While it reduced market risks for the farmer, it also encouraged companies to invest in farming indirectly.

The result is obvious everywhere, but nowhere more so than in the 500-acre farm of the Patel brothers in Dolpur in the district of Sabarkantha, in the northeast of the state. Jitesh and Bhavesh, both having done masters in agricultural science, have managed to bring together plots owned by family members and friends and grow potato with modern techniques. They contract out their future production to Balaji, ITC and Pepsi. Their high yields have won them admirers. Each week, their farm sees at least 300 visitors from the state as well as Punjab and Uttar Pradesh, keen to learn their key to success. The brothers now act as consultants to other farmers. Very soon, the Patels will be investing Rs. 4 crore on a greenhouse to grow capsicum, tomatoes and muskmelons.

Gujarat has also stepped up its extension services significantly in the last decade, taking knowledge from research campuses to the farms. In the last five years, Krushi Mahotsavs (Farm Festivals) have grown in scope. As many as 18,600 villages host the event on the Akshaya Tritiya day (an auspicious day in the Hindu Calendar falling in May-June). University professors, government officers and even ministers are required to spend time with farmers, listening to their problems and developing solutions. While the quality of work in these fairs needs to improve according to farmers, and the researchers need to gain more practical experience, their impact in spreading awareness about things such as soil quality is undeniable.

PAGE_BREAK

But the big change in Gujarat has come from the conservation of the most crucial resource for farming – water.

Gujarat started by planning large dam projects such as Sardar Sarovar Project (SSP) to achieve a breakthrough in agriculture. To this day, its progress remains limited. Only a small portion of the potential command area has been covered with irrigation facilities. The canal irrigation system of Gujarat, while improving, is not adequate for its needs. To take water to the really dry areas, the Narmada dam’s height must be raised which the government is trying to accomplish. However, even that high-cost strategy will not be enough to fulfil the demand for water. “Agriculture suffered for centuries in Gujarat primarily because it did not have water,” says P.K. Laheri, formerly chief secretary of Gujarat and managing director of Sardar Sarovar Narmada Nigam and now a director with Torrent Power. “It improved when we began taking the waters of the Narmada to irrigate our fields. Then, when the dam was built, more land came under cultivation. But a lot of land continues to be rain-fed.”

That’s why Gujarat has embarked on a major exercise to conserve water and use it more efficiently in the fields. The most important turning point in the state’s agriculture has been the innovative management of its groundwater resources. The state has adopted a combination of rainwater harvesting – that traps water that would otherwise drain away – and micro irrigation – that supplies each drop of water more efficiently and directly to the plant. The movement has been a roaring success and stories abound of conversion of barren lands into fertile farms, rising yields and falling costs of cultivation across the state.

Between 2001 and 2006, Chief Minister Narendra Modi ordered the building of check dams wherever possible. His slogan was that rain water in the fields should remain there and the water in rivulets should remain there too. There was little sense in letting all this water drain into the sea. The strategy worked. And farmers began to see a rise in water tables year after year. Modi also streamlined the supply of electricity to water pumps. Because they were getting subsidised power, farmers had little incentive to save on its use or keep pumps in good order to lower power consumption. As a result, much power was wasted. Also, power theft was widely prevalent. Further, farmers faced the problem of low-voltage power that helped nobody.

Modi, in his second year in power, ordered the uninterrupted supply of quality power to farms for three-phase pumps for at least four hours a day, but only in night. This ensured that farmers could use the pumps only for a limited time and had to make the most of it. During the day, industry got quality power. The scope for power theft reduced. Farmer groups were initially angry with the changes, but came around after some persuasion.

The government was still painfully aware that the key bottleneck would be availability of water. Higher water tables and taller dams could go only so far. The real need was to save water and use it more efficiently. There was a need to champion micro irrigation. That’s when the government formed Gujarat Green Revolution Company (GGRC).

PAGE_BREAK

The new company adopted a twin strategy. First, it made the subsidy for micro irrigation available to all farmers, not just the poor ones. The initial investment to install the plumbing for micro irrigation could be prohibitive. Even after the subsidy, it would come to a big sum and poor farmers would hesitate to make that investment. But for the richer ones, the subsidy made it a compelling proposition and they jumped in. This, in turn, showed the way for poorer farmers who followed.

Second, GGRC tightened norms for the subsidy scheme ensuring that companies didn’t sell pipes and move on to clinch more sales. It insisted that micro irrigation technology providers also offer extension services. To ensure compliance, it introduced a series of norms – like how many agronomists must be employed for a given expanse of land, how many field visits the experts must make and even the price at which the systems could be sold. “The farmer needs handholding,” says C.L.N. Rao, head agronomist with Netafim India, market leader for micro irrigation systems in the state. “And once a farmer sees money coming in... [the farmer] becomes the champion for other farmers as well.”

Now there is even talk in Gujarat that the government will order that power connections will be granted only if a farm has micro irrigation facilities. This is so because drip, sprinkling and spraying systems that come under the definition of micro irrigation deliver water very close to the plant or even to the roots. They avoid delivering water where it is not needed, thus reducing the growth of weeds. They don’t allow water to seep too deep into earth.

Gujarat is also studying a policy adopted in Raipur, where electricity tariffs for pumps of more than five horsepower invite the higher industry-level tariffs and the smaller pumps enjoy the subsidised agricultural tariffs. This is to encourage farmers to draw less water. It is also aimed at making sure all farms get irrigated, not only those owned by rich farmers.

Micro irrigation is spreading fast across Gujarat. Back in the Dolpur farm of the Patel brothers, a modern drip irrigation system is at work. They have had to pay the full price for it because they chose to go in for micro irrigation before the subsidy scheme was set in motion. The brothers bring scientific knowledge of soil, water and weather to their farming practices. They have even built a small soil and water analysis laboratory. “We know that while one well would normally irrigate three to four acres, using newer automated techniques, we could irrigate 15-20 acres,” says Jitesh Patel. The modern systems have made sure that the four hours of power are plenty for their large farm. “We sleep better, have saved on labour and also on water,” he says adding, quite proudly, “We now enjoy a higher status in society.”

Comments

0 comment