views

Seoul: Park Hee-sung, a 78-year-old North Korean former agent who has been held in the enemy South for close to half a century, remains staunchly loyal to his homeland, the ruling Kim family and its Juche ideology of economic self-reliance.

A trim, neat man, Park is one of around two dozen North Korean operatives trapped in exile in affluent South Korea. He lives in a charity house in central Seoul with another former agent, 79-year-old Kim Young-sik, and dreams of the day he can return freely to the northern part of a unified Korea.

For Park and Kim, North Korea, which for several weeks has threatened the United States and South Korea with nuclear war, is no menace to world peace, rather a plucky nation that single-handedly stands up to American bullying.

"For an hour, I wish I could live with my loving family in the party's embrace in my peacefully unified nation and die," Park told Reuters, as Kim played "Arirang", a folk song regarded as the unofficial anthem of both Koreas, on a traditional harp.

In the garden of the quiet two-storey house, the two tend their walnut, cherry, apple and persimmon trees and a small vegetable plot.

After serving in the 1950-53 Korean War, Park worked as a projectionist at a movie theatre. In 1959, he was called up by the ruling Korean Workers' Party to ferry North Korean spies to the South and bring them back home across the border.

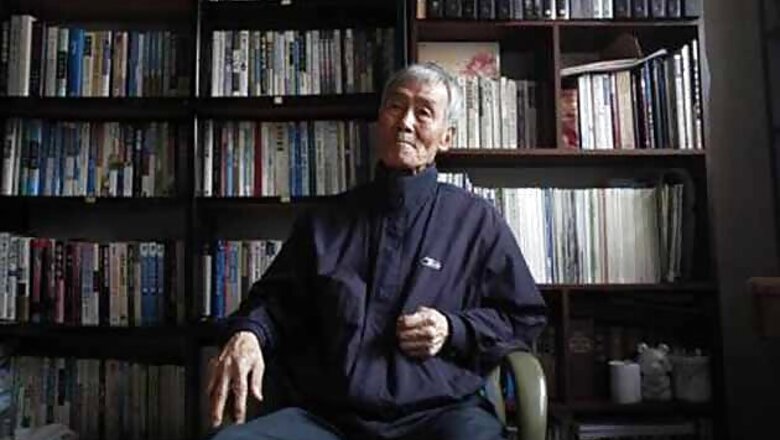

Sitting in his room neatly packed with books on North Korea, Park thumbs through a map of the peninsula, showing the route he used to cross the border.

He was captured in 1962 in a gun battle with South Korean coastguards in a bay as he and three comrades tried to make contact with an operative returning from the South. In the shoot-out that killed his boat's captain, Park was wounded in the thigh and arm, and crawled on to wetlands expecting to die. Hallucinating from his wounds and the cold, he says he dreamed of waving goodbye to his son, who was then just 16 months old.

Sentenced to life in prison, Park was released on parole in 1988 after signing a paper renouncing his beliefs. A thaw between the two Koreas - still technically at war after an armistice rather than a peace treaty ended the Korean War - saw 63 North Korean prisoners returned to Pyongyang in 2000, where they received a hero's welcome. Park applied to join a second large-scale repatriation, saying he had been tortured to sign the earlier renunciation of his beliefs.

His transfer home never happened, leaving him trapped in enemy territory. Both Park and Kim say, even now, they can't go home. "There's still security supervision. I'm told to report, even though I'll die tomorrow or the day after. When I was working, the police were making a fuss, thinking I ran away," recalled Kim.

Park, too, insisted the police would prevent them from returning home. "They're watching us even now. The cops would chase us," he said, adding that, even if they could flee, they didn't want to make life tougher for those left behind.

"People here have asked me ... what would happen to the rest if I left? I've never considered it (fleeing), as the watch would be stronger and life would be more difficult."

In an emailed reply to Reuters for this article, South Korea's Unification Ministry said repatriating "unconverted long-term prisoners should be considered cautiously, taking into account humanitarianism, the special nature of South-North Korean relations, issues with domestic law and popular consensus."

Despite most independent assessments that North Korea's economy has shrunk in the past 20 years, Park believes his homeland is the "strong and prosperous" nation portrayed in its official Juche ideology - a fusion of Marxism, extreme nationalism and self sufficiency centred on the Kim family cult as its defender.

"North Korea is doing well now ... No one here could imagine the arduous march," he said, using the North Korean term for a famine that devastated the country in the 1990s, killing an estimated 1 million people.

"With our belts tightened, we have been unyielding and resisted the United States' threats of preemptive nuclear strikes. That's unprecedented in the world," the softly-spoken Park said, suddenly raising his voice.

Park firmly believes the Workers' Party is taking care of his wife and son and, after all these years, he has not contemplated remarrying. "I have never thought about making families or getting married here. My wife and baby, these two only waiting for me to return, comes into my head. My conscience doesn't allow me," he said.

On his release from prison, Park eked out a living on construction sites and in furniture factories, always under the watchful eye of the local police. Five years ago, he settled in the house in Seoul run by a charity that helps North Korean ex-prisoners. Park and Kim are the only two left of a dozen or so who lived there. The death in February of a "comrade" leaves around two dozen veteran former spies and guerrilla fighters dotted around the South in various locations. Most were handed life jail terms, but have since been released.

Park's neatness and his meticulously tidy room contrast with the bearded and stocky Kim's room of clutter. "We can't eat together," says Kim. "Park is clean and impatient, but I'm laid back. Without a social conscience, I'd kick and get out of here."

Park fears that the heightened tensions between the two Koreas mean he will likely die in the South. "If I were lucky, I'd go and meet my family. But if luck's not with me, I'll die in a ditch. Here, it is death in a ditch," he said.

Every Thursday, both men join a small demonstration in the city centre against South Korea's National Security Law, which is used to imprison those spying for the North. Passers-by abuse them, calling them "stupid" and "commie", they said.

"We respect Kim Il-sung, Kim Jong-il and Kim Jong-un. They are like our family," said Kim, referring to the three generations of the ruling dynasty in Pyongyang.

Comments

0 comment