views

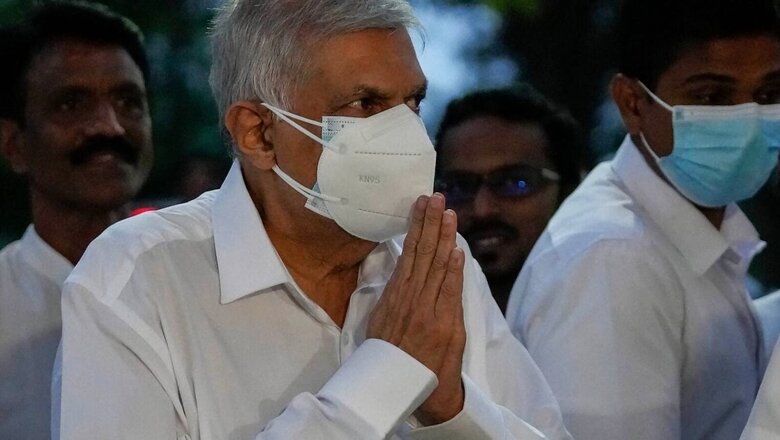

The election of Ranil Wickremesinghe as the new President in Sri Lanka through a parliamentary process to fill the position left vacant by Gotabaya Rajapaksa, who fled the country, is supposed to be a resolution. However, the entire process has contradictions embedded in it and is unlikely to be a real solution as people see Wickremasinghe as a Rajapaksa acolyte. His ouster was as much a demand of the “Aragalaya” as the Rajapaksa’s.

It is evident that Mahinda Rajapaksa is not absconding; he controls his party in Parliament, and has enough clout to defeat his dissidents.

The problem began with an economic crisis, which led to a political crisis. That saw the resignation, first, of the Prime Minister, Mahinda Rajapaksa, and thereafter the President, Gotabaya. Thus far, politics was in command, not economics, which is urgent.

What the Sri Lankan parliament has done, however much the Aragalaya may dislike it, is the constitutionally correct thing. Parliament elected a President, Ranil Wickremesinghe, a twice-defeated presidential candidate. He is elected by the people who defeated him earlier and that is the beauty of Sri Lankan politics. Ultimately, he won because some people who ditched him at the last election ultimately voted for him this time, giving him the 134 votes over

the 87 for the Opposition. The split in the ruling party did not help.

Significantly, Mahinda Rajapaksa and his son, Nimal, were both in Parliament voting for their candidate to show who is in command of a majority. They were aided by the fear among MPs that their homes would be destroyed as many had so suffered and only a strong government would protect them. Wickremesinghe promised to rebuild their homes and he shared their pain as his own home was destroyed too. The Aragalaya did not contend with this reaction and painted their activity as anarchy.

Wickremesinghe’s ability to piece together a proper coalition for a stable government which could then negotiate with the IMF is constrained due to the perceived lack of public legitimacy. But he is the constitutionally elected President. The Aragalaya now threatens to continue to seek Wickremesinghe’s exit. They are among the same people who brought Rajapaksas to power but have been disillusioned.

The Aragalaya wants a new socio-political contract and has a detailed manifesto. That manifesto is unlikely to be accepted by any political party which wants to survive in the current scheme of things. The Aragalaya believes that its struggle was not only to oust the Rajapaksas, but to change the system. This contradiction is not going away in a hurry.

Gotabaya missed a trick when he was still in power and persuaded his brother to quit as prime minister. He could have brought in a more acceptable non-political person as PM and formed a cabinet of technocrats by bringing in people through the national list into parliament. He failed to show that statesmanship because his party, and now the entire parliament is watching out for the next election and not for the survival of the country, economically.

Separately, there is a major lack of trust in Sri Lanka’s way of doing things. Had trust with India not dented perhaps India would by now have called an Aid Sri Lanka conference and marshalled international institutions beyond the IMF as well as bilateral donors under India’s leadership to support Sri Lanka. At present, India is the only country really looking out for Sri Lanka and in recent months, it has already added 7.5 percent to Colombo’s outstanding debt of $51 billion. Today, every country is preoccupied with its own issues and nobody is really bothered about Sri Lanka except India. This is now self-evident. The solutions also lie in Sri Lanka. Dealing with India in an acceptable manner needs to be part of the Sri Lanka Compact that Colombo needs to craft.

For far too long, Sri Lanka has worked on policies which at times of struggle or pain, look to India for the balm. When fit, they go back to cocking a snook and providing strategic challenges to India. This is not a Rajapaksa preserve. In 1971, when the JVP almost overthrew Bandaranaike’s SLFP government it was India which helped her but that did not prevent Sri Lanka from providing facilities to Pakistan to suppress Bangladesh a few months later. Similarly, in 1988 general elections, the upsurge of the JVP saw India quietly helping Sri Lanka, but the new president, R Premadasa, only took four months to embarrass India by announcing publicly his demand for the repatriation of the IPKF.

Sri Lanka has made it a pattern of reaching out to India when necessary, and otherwise showing strategic independence. Such non-alignment may be good, provided it pays dividends and today nobody is coming to the aid of Sri Lanka other than India.

What are the next steps? President Wickremesinghe is clear: It’s the economy and they must get on with it. A new government involving all parties in Parliament may work to provide the stability needed now.

The Aragalaya’s demands cannot be wished away and since the legitimacy of the political system is being questioned, the correct way may be to set up a roundtable conference to discuss changes in the Constitution. It is important that the new social contract is inclusive of Tamil and Muslim sentiment and tries to override the ethnic divide and seek futuristic engagement.

The writer is a former Ambassador to Germany, Indonesia & ASEAN, Ethiopia & the African Union. Views expressed are personal.

Read all the Latest News and Breaking News here

Comments

0 comment