views

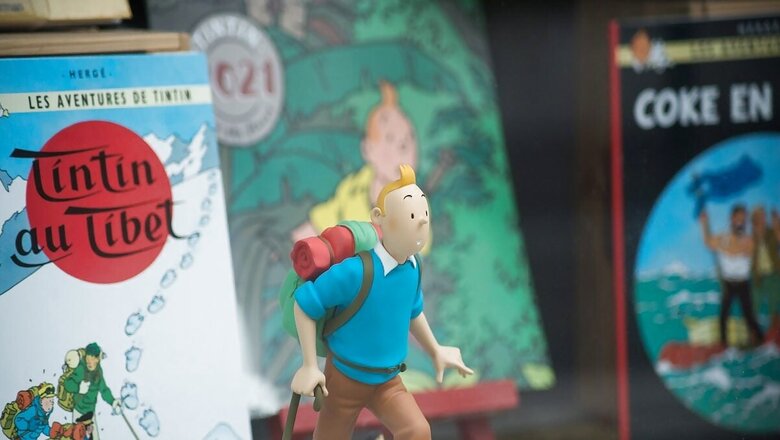

May 22 was the birthday of arguably one of the world’s most beloved cartoonists of all time, Georges Prosper Remi, known by the pen name Hergé, who mesmerised readers across the globe with his iconic creation of Tintin. Even though the Belgian cartoonist’s magnum opus series ‘The Adventures of Tintin’ has been translated into around 100 languages and more than 300 million copies have been sold across the globe since its creation 94 years ago, the globe-trotting reporter has some unique connections with, of all places on Earth, Taiwan. The island has been one of the few countries Hergé visited, even though none of his adventures mentioned the geopolitically sensitive T word in any of the 24 books of the gung-ho fictional character with his trademark quiff.

Generalissimo’s grand invitation

It is said that modern Taiwan’s founder Chiang Kai-shek was one of the first heads of state to get mesmerised by the baby-faced journalist. After reading one of Hergé’s earliest Tintin stories, The Blue Lotus, originally serialised in the weekly Belgian newspaper supplement Le Petit Vingtième between 1934 and 1935, and set in China during the Japanese invasion of Manchuria, in 1931, the Generalissimo, who was then leading the Nationalist Chinese resistance against the Japanese imperialist forces in the Mainland, sent a personal invitation to the Belgian creator of Tintin to visit his country at the behest of his wife, Soong Mei-ling.

Soong sisters and Tintin

Interestingly, Mei-ling’s elder sister Soong Ching-ling also strongly connected with The Blue Lotus, which was published as a book in 1936. Ching-ling, who happened to be modern China’s founding father, Sun Yat-sen’s widow and future vice president of the Communist-ruled People’s Republic of China (PRC), had a friend in Belgium called Lou Tseng-Tsiang or Lu Zhengxiang. He had once served as a former prime minister of her husband, Sun, and later became a Benedictine monk at the abbey of St Andre in Bruges, taking the name Dom Pierre-Celestin Lou. According to Roger Faligot’s book ‘Chinese Spies: From Chairman Mao to Xi Jinping’, Hergé was introduced to Chinese sculptor Zhang Chongren through Lou for the first time. The rest, as they say, is history. A young Zhang, then a student at Academie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, helped Hergé authentically create the Chinese scenes and settings for The Blue Lotus. The Belgian artist’s legendary camaraderie with Zhang also resulted in the creation of the adorable character of a little boy, Chang Chong-Chen, who, after making his debut in The Blue Lotus, made a remarkable return in Tintin in Tibet as an air crash survivor in the high Himalayas. Notably, in the original French version of the comics, Chang was christened as Tchang Tchong-Jen. On the other hand, French investigative journalist Faligot’s seminal work also mentioned, “To help him with his research, Dom Pierre-Celestin Lou lent Hergé the book he had published the previous year, The Invasion and Occupation of Manchuria.”

Madame Chiang Kai-shek & Chang

In her dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Cambridge, titled ‘How Tintin Met Tchang: The Sino-Belgian Catholic Network in the Early Twentieth Century,’ scholar Zhiyuan Pan noted, “Although the comic had not officially entered China, the first lady of the Republic of China, Soong Mei-ling learned of it through a source of information which remains unclear from current research.” However, there is also an unverified claim by the Chinese version of Wikipedia that Mei-ling or Madame Chiang Kai-shek, herself translated one version of Tintin in the early Republic of China (around 1930-the 40s), and it was “designated as a good children’s book, but it should have been out of print after many wars.”

Taipei-based Professor Albert Tang Wei-min, a Tintin aficionado, who also visited Hergé Museum, among other places associated with the adventure series, noted, “Since Madam Chiang was associated with the publications of several literature and translation works, there may be a good chance of her bringing out a Tintin book in Chinese before the Japanese aggression, but I have never come across any such information before.” But the academic from Fu Jen Catholic University in New Taipei City informed, “Zhang Chongren’s mentor was Ma Xiangbo, one of the founders of my university and the Tushanwan Orphanage near Shanghai, where Zhang grew up after losing his mother at an early age. Tushanwan was a cradle for many Chinese artists, including Zhang, who benefitted from art-exchange programs and regular visits from Europe. An aged Ma, who took Zhang under his wing, used his contacts and connections in Belgium to play a key role in helping Zhang to study in Belgium and eventually get introduced to Hergé. On the other hand, Madame Chiang Kai-Shek was the president of my university for 17 years.”

Three-decade-old invitation

In addition, Pan, in her theological thesis, mentioned, “As recorded in the diary of Lu Zhengxiang on 7th December 1939, he received a telegram from Chongqing from the Minister of Information, Dong Xianguang (Hollington Tong): Madame Chiang invites Hergé. Reimbursement provided. Lu told Dom Neut of the invitation, and he contacted Hergé the next day. According to the biographer Benoît Peeters, the real intention of this telegram was to invite Hergé to draw for the educational sector of the Chinese government, probably in a weekly for Chinese youth. Ultimately, Hergé could not go because he was doing military service before being declared unfit due to sinusitis and boils in May 1940. A few days later, Germany launched attacks on Belgium and began its occupation, which lasted for the next five years.”

Hergé’s long-pending visit, however, got materialised after more than three decades. But by then, Chiang Kai-shek had left the Chinese Mainland to relocate the government of the Republic of China to Taiwan as its president, while there was a geopolitical concern as well as a dilemma for the Belgian comics czar. In the book, ‘The Real Hergé: The Inspiration Behind Tintin,’ its author Sian Lye mentioned, “However, in November 1972, Hergé received a letter from Taiwan. The letter was from Mr. Tsai, who was reissuing the invitation from thirty-five years earlier to visit the country from the same government, under the leadership of the same man, and in the name of the same people.”

Dilemma before departure

But the Cold War-era decade of the swinging seventies that saw both the Communist Mainland and the Nationalist (Kuomintang) Taiwan tussling for the legitimate rights of “China” in the diplomatic sphere also resulted in some dilemma for Hergé. “This had been instigated by a journalist and friend of Hergé’s, Dominique de Wespin, who visited Taiwan in 1971 and reminded her contacts of the invitation they had made to Hergé so long ago.” The book further claimed, “Hergé was keen but sought advice from Father Neut, who had passed on the original invitation to him. But Father Neut, who was more conscious of the political situation in China and Taiwan at that time, urged him not to accept, telling him that while in 1939 Chiang Kai-Shek had been the leader of the Chinese state, he was no longer in charge. Neut felt that the days of his government on Formosa were numbered and added that if Hergé were to visit Taiwan, the political situation in that area was so tense it would make it extremely difficult for him to ever visit China.”

But eventually, Taiwan had the last laugh. “Undeterred by Father Neut’s advice, Hergé accepted the invitation and travelled to Taiwan,” Lye informed.

In 1973, just two years before both Mei-ling and the Generalissimo passed away, Hergé was in Taiwan on its government’s invitation and was awarded a Golden ‘Lei’ medal at the Taiwan National History Museum in recognition of his support of China during the Sino-Japanese conflict in The Blue Lotus. Hergé’s personal album has a newspaper clipping about his felicitation in Taipei and a photo of him posing in front of a Buddhist temple that has an uncanny similarity with Taipei’s historic Longshan temple in Wanhua district.

Much-awaited reunion with Chang

Another significance of Hergé’s Taiwan trip was that it was part of his quest to search for his long-lost Chinese friend Zhang with whom he lost contact after the latter returned to China after completing his course in Brussels. But, unfortunately, despite visiting Taiwan with high expectations of finding the real-life ‘Chang,’ Hergé had to return disappointed. Neither could he find the Chinese artist, nor the Taiwanese government could provide him with a single piece of information about Zhang.

As luck would have it, Shanghai-born Zhang remained on the Mainland since returning from Belgium and passing through the subsequent upheavals and turmoil in his country. He had, as per Pan’s paper, “suffered a great deal because of his Catholic faith and the sculpture he had made of Chiang Kai-shek in 1946 was taken as ‘counter-revolutionary evidence’ against him: his property was confiscated, and most of his artworks were destroyed. He was beaten and publicly humiliated before being sent to do farm labour at a May 7th cadre school.” A few years after Hergé’s Taiwan visit, the erstwhile victim of the Mao-era Culture Revolution was rehabilitated by the Deng Xiaoping regime in 1979. Moreover, Zhang was eventually connected to Hergé through some key officials of the Deng regime, but the Belgian cartoonist’s efforts to visit China were believed to be jeopardised by his previous Taiwan trip as Lye highlighted, “as he had visited Taiwan, it was now incredibly difficult for him to get a Chinese visa.”

On the other hand, Zhang’s approval applied in China to be allowed to go to Belgium was pending for a long time, and it would take years before the two friends managed to have their long-awaited and high-profile reunion in 1981 at the invitation of the French government. But Hergé’s wish to visit the mainland, the only country featured in two different Tintin adventures, remained unfulfilled as he passed away two years later.

Tongue-wagging Tintin Legacy in Taiwan

But sadly, like China, Tintin was published in Taiwan only in the mid-1990s when China Times Publishing Company brought out a translation series, and later, in the 2000s, another Taiwanese publishing major, Sharp Point Press, printed the Mandarin version of the adventures of the Belgian boy journalist with their special editions coming out as late as 2018. “I remember being introduced to Tintin when I took my son to the previous branch of Alliance Franchise in the early 2000s as they decorated the French language classrooms with Tintin graffiti. However, those wall paintings no longer exist as they later shifted to the current National Taiwan University (NTU) campus,” rued Professor Tang.

Today, in Taiwan, akin to the Mainland, the Chinese name of Tintin – Dingding (丁丁) is often used as a slang for phallus since the Chinese character resembles “JJ,” which is the short form for Jiji (雞雞), the word for penis in Chinese. Besides, a popular pharmacy chain across Taiwan is named after the intrepid investigative reporter, while the Bon Hotel in the heart of Taipei is a tiny Tintin-themed boutique hotel located on the 4th floor of a commercial building. Nonetheless, Taiwan probably remained the only country besides the USA where Tintin’s Belgian creator had an official visit, not any transit, outside Europe.

The author is an independent journalist and MOE Huayu Scholar in Kaohsiung, Taiwan. Views expressed are personal.

Comments

0 comment