views

It’s a goal. A goal which India wasn’t even willing to score. In fact, India was happy playing the ball in its own half. But such has been the Maldivian ingenuity to score a self-goal, especially since the formation of a new government this year, maybe emboldened by China’s hidden hands in its support, that they have not just jumped on to the Indian half but also ensured that a goal is scored on their own side.

When Prime Minister Narendra Modi visited Lakshadweep, he did what he would usually do while visiting a part of India: He posted photos of his stay in Lakshadweep; he praised its pristine beaches; and, he urged Indians to prioritise domestic trips over foreign visits. He then posted his photos and penned his thoughts on Lakshadweep.

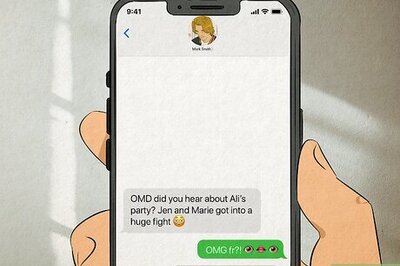

Like in the past, it did raise curiosity in social media, which went on an overdrive, with many Indian users comparing Lakshadweep with the Maldives. Lo and behold, a few Maldivian ministers took the bait and made unsavoury comments about Prime Minister Modi and India. The result has been catastrophic for Maldives: Its primary money-minting industry, tourism, is in tatters, with Indians going in for mass cancellation and EaseMyTrip, one of India’s biggest online travel platforms, suspending flight bookings to the island nation.

As per data from the Maldives’ tourism ministry, Indians in 2023 accounted for 11.2 per cent of the total tourist arrivals — 18.42 lakh — in the island nation, with Russia being a close second with a share of 11.1 per cent.

The fact of the matter is that Modi was doing what he ought to do as a Prime Minister. What’s ironic is that it took the Indian leadership so long to wake up to Lakshadweep. India’s Lakshadweep policy often reminded this writer of the country’s now-discarded border development programmes, especially those related to infrastructure in the Northeast. For decades, people were made to believe that the roads in the Northeast, especially in the areas bordering China, should not be developed as this would provide the invading Chinese troops easy access to India’s mainland. The result of this defeatist mindset was that the people living in the bordering areas of Arunachal Pradesh, especially, would look askance at the broad, multi-lane highway running up to the Line of Actual Control (LAC) on the other side, while living amid state-imposed poverty and drudgery.

The policy to keep Lakshadweep off the tourist map reminds us of the same beaten track. For, the agents of climate change won’t discriminate in favour of Lakshadweep if neighbouring Maldives and mainland Kerala indulge in unsustainable development and wanton commercialisation. Also, isn’t it an elitist mentality of those residing in the mainland to incessantly exploit the planet for human whims and fancies, but keep these people in the dark ages in the name of climate change and ecology?

In the early 1980s, the Maldives was one of the world’s 20 poorest countries. Within three decades, it not just pushed itself in the middle-income country, but also showed massive improvements in the healthcare and education sectors, with a life expectancy of 74.8 and a literacy rate of 98.4 per cent. Lakshadweep, in contrast, remained stuck in a time warp. An archipelago of 36 islands, of which 11 are inhabited with about 70,000 people, it has a low per capita income and high unemployment level of 13 per cent, as per the data provided by the UT Administration. Even after seven decades of Independence, Internet connectivity is in an elementary stage in Lakshadweep, especially at a time when the world is taking a giant online leap forward.

As the saying goes, life finds a way, so will these people in the archipelago, even if all doors of development are closed. If they don’t find education and jobs, they will find other means for survival and livelihood, often playing at the hands of those inimical to India’s interests. No wonder, in May 2022, the Directorate of Revenue Intelligence (DRI) and the Indian Coast Guard (ICG) intercepted two Indian ships off the coast of the Lakshadweep islands and seized 218 kg of heroin worth Rs 1,526 crore.

In this backdrop, Prime Minister Modi inaugurating the Kochi-Lakshadweep Islands Submarine Optical Fibre Connection project, among various projects, worth more than Rs 1,150 crore covering a wide range of sectors including technology, energy, water resources, healthcare and education, should be welcomed. Addressing the gathering, the Prime Minister said that the project “will ensure 100 times faster Internet for the people of Lakshadweep. This will improve facilities like government services, medical treatment, education and digital banking. The potential of developing Lakshadweep as a logistics hub will get strength from this”.

Better connectivity has an important role in promotion of tourism and regional development. Until now, only low-capacity aircraft (such as ATR aircraft) were able to land at the Agatti airport, due to which national and international tourists would come in small numbers. If reports are to be believed, the government is now moving ahead with plans to develop a new airport at Lakshadweep’s Minicoy Islands where it would operate both military and civilian aircraft.

Similarly, the islands have great potential in the coconut and fishing sectors. There are around 10.5 lakh coconut trees on the island and about 10.5 crore coconuts are produced annually in the Union Territory. Likewise, Tuna fish are found in abundance in the sea there. Approximately 25,000 metric tons of fish are caught every year, of which 92 per cent are Tuna fish. But due to lack of proper arrangement of ice and fish processing, fishermen do not get fair prices for their catch.

It is no one’s contention that the ecology of the islands must be compromised, but one must realise that this can’t be an excuse to deprive the people of their right to life with basic facilities. And getting stuck in backwardness doesn’t guarantee ecological safety. Not many outsiders, criticising the government for “ecologically endangering” the archipelago, know that electricity for Lakshadweep is largely produced from diesel generators. This is having a very adverse impact on the environment there.

Last week, Prime Minister Modi inaugurated Lakshadweep’s on-grid solar project featuring a Battery Energy Storage System (BESS). The initiative, covering the islands of Kavaratti and Agatti, is expected to offset 58,000 tonnes of CO2 emissions and save 190 lakh litres of diesel over its lifetime.

As the Covid-19 crisis has shown, madhyam marg (middle path) is the way out. For, during the pandemic, with the disappearance of travellers, and flights and cruise ships on hold, carbon emissions saw a record drop and wildlife a new leash of life. But, on the flip side, there was a rise in cases of poaching and illegal fishing, especially in developing nations. One has seen in India too, how wildlife, especially tigers, have been saved from poachers by, first, encouraging tourism, and then by making locals join the wildlife bandwagon: Letting the locals have stakes in Lakshadweep’s tourism will make them the vanguards of the islands’ ecology.

Development and sustainability don’t have to be the antithesis to each other. The same holds true for tourism and ecological safety. Lakshadweep must follow the middle path of sustainable development. This will be a win-win scenario for everyone. Except those who have vested interests in manufacturing dissent!

Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

Comments

0 comment