views

What is the door-in-the-face technique?

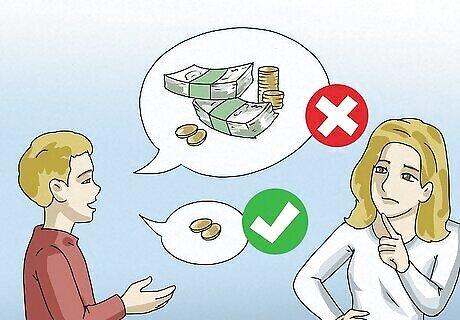

The door-in-the-face (DITF) technique is a persuasion strategy. It is commonly studied in social psychology. First, the asker makes an extreme, unrealistic request that the other person is sure to turn down—effectively slamming the door in the asker’s face. The asker immediately follows up with a second, more reasonable request (which was the real request all along). According to research, the recipient is much more likely to agree to the smaller request after first being presented with the larger, more outlandish option.

It was introduced in 1975 by psychologist Robert Cialdini. In their original experiment, Cialdini and his colleagues approached students and asked if they would volunteer to be unpaid counselors at a juvenile detention center for two hours a week for two whole years. When the students refused, Cialdini and his team asked if they would volunteer to escort juveniles from the detention center on a two-hour trip to the zoo. 50% of the students agreed to the second request when they were first presented with the more outlandish request. When a different group of students was presented with only the second, smaller request, only 17% agreed. In other words, the experiment showed that people may be more likely to agree to a target request when they’re first presented with a larger request.

Examples of the Door-in-the-Face Technique

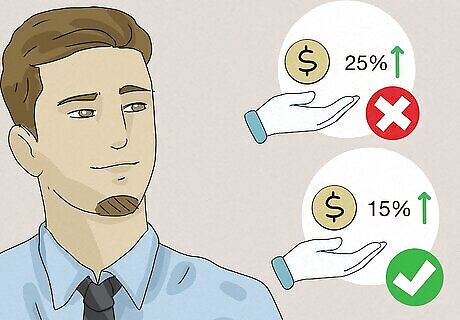

The DITF technique is commonly used in sales and negotiations. It can also be used in personal situations when one person needs to ask a favor, but they’re worried the other person will refuse. Here are some examples: At a garage sale, a customer asks for the price of a desk. The seller first says $250, which he knows the buyer will turn down. After the buyer refuses, the seller says, “Okay, I think I could sell for $100.” Having already turned down the more outlandish price, the buyer is more likely to accept. When negotiating a pay increase, an employee first asks their boss for a 25% raise, though this request likely won’t be met. After their boss says no, the employee makes their true request for a raise of 15%. An entrepreneur is trying to get funding for his new business. He starts by asking a potential investor for $5 million dollars. When the investor refuses, the entrepreneur follows up with a request for a $1 million dollar investment. An employee of a non-profit organization asks someone if they would be willing to volunteer for a 5-hour beach clean-up. When the person says no, the employee asks if they’d be willing to donate $5 to the cause instead. A girl wants to borrow her older sister’s shirt. First, she asks to borrow a whole outfit and shoes, which her sister predictably refuses. She then says, “Okay, fine. Can I at least borrow the shirt?” Her sister is more likely to agree to this request because it seems more reasonable compared to the first one.

Why is the door-in-the-face technique effective?

There are several possible reasons the DITF technique works so well. Some people believe that it’s because the respondent feels guilty for refusing the first request, so they agree to the second one. Cialdini, the psychologist who identified the technique, believed that the rule of “reciprocal concessions” was the best explanation. Cialdini explained that, when following up the first request with the smaller request, respondents were more likely to view the second request as an offer of compromise. And, because humans are socially conditioned to follow the norm of reciprocity (which says we should repay kindness with kindness), the respondent felt obligated to concede to the second request. In other words, they believed the asker was compromising by downgrading from the larger request to the smaller one. As a result, they felt compelled to agree.

How to Use the Door-in-the-Face Technique

First, make your bigger, more unreasonable request. Your first request needs to be unrealistic, but not completely out of the realm of possibility. If it's too outlandish, it might offend the other person or tip them off to the fact that you’re using a persuasion tactic. To avoid this, think carefully about your audience and your relationship with them. For example, you wouldn’t want to ask a casual acquaintance for $500—this would surely alert them that something’s up. Example 1: When selling your handmade jewelry at a flea market, you tell a customer that a necklace costs $50. Example 2: You ask your teenage son to clean the whole house before he goes to hangout with his friends. Example 3: You ask a friend to stay at your house for the whole weekend to dog sit while you’re out of town.

Immediately follow up with your actual request. When the person refuses your initial request, present your next request as if you’re compromising or conceding something. This persuasive tactic makes the other person more likely to agree to your second request (which was your real goal all along!). Here are some examples of how to phrase it: Example 1: “I’ve been asking for $50 for each necklace, but it does look so amazing on you. I think I could sell it for $30, if you’re still interested.” Example 2: “Okay fine, I know you have to be there by 6, so I guess that isn’t enough time to clean the whole house. Can you at least tidy up your room before you head out?” Example 3: “No worries—I totally get that it’s a lot for me to ask you to dog sit Bailey the whole weekend. Do you think you could just check in on her Saturday morning and Sunday morning to refill her food and water bowls?”

Be thankful and gracious if the other person agrees. If the other person ends up agreeing to your second request, thank them sincerely and genuinely to keep the good vibes flowing. If the respondent miraculously agrees to your first extreme request—go with it! You’ve had a stroke of luck and got more than you bargained for.

Door-in-the-Face Technique vs. Foot-in-the-Door Technique

The foot-in-the-door technique is another sequential request strategy. It involves starting out with a small request, and then making a bigger, more substantial ask. The respondent is more likely to agree to the second request than they would have been if it was presented on its own. The foot-in-the-door technique is essentially the opposite of the door-in-the-face technique, but they have the same desired outcome—getting someone to agree to a request. For example, a non-profit employee using the foot-in-the-door technique might start out by asking a passerby if they would be willing to sign a petition in support of their cause. Once someone agrees and starts engaging in conversation, the employee asks if they’d be willing to make a $5 donation as well.

Other Compliance Techniques

Disrupt-then-reframe technique This persuasion strategy involves making a strange or odd request to confuse and disarm someone, then making the same request in a different, more “normal” way. In the original experiment for this technique, salespeople offered buyers a set of notecards for the price of 300 pennies. When buyers appeared confused, the salespeople followed up with a reframed statement (“That’s $3. It’s a bargain!). Buyers who were pitched in this way were more inclined to purchase the notecards than buyers who were simply offered the cards for $3 from the start.

Low-ball technique This technique starts with making a request and getting someone to agree to it. Then, at the last minute, the requester changes the terms of the deal. For example, someone using this technique might initially agree to buy their friend’s old bed frame for $75. When they go to pick up the bed frame, they might say something like, “I’ve been thinking about it, and I actually don’t think I can spend more than $50. I hope that’s okay.” This tactic can be seen as a bit more manipulative and unethical than the others, so use with caution.

That’s-not-all technique This strategy is used by sellers and marketers to convince undecided customers to buy a product (think infomercials or sales people standing outside stores at the mall). It involves making a request and tacking on an additional reason to agree to it before the customer has a chance to respond. For example: “For one day only, we’re offering 15% off all candles! And that’s not all—when you make your purchase, you’ll get a free sample of body lotion.”

Comments

0 comment