views

X

Research source

Conducting Post-Judgment Discovery

Draft interrogatories to locate the person's assets. Interrogatories are written questions that the person must answer as though they were under oath. Unlike written questions you might have sent the person before trial, there are no limits on post-judgment interrogatories. The purpose of these questions is to identify assets or funds the person has that can be taken or sold to satisfy the judgment. At a minimum, you should include questions about the person's spouse and employer, their income and expenses, descriptions and locations of their real and personal property, and the names and addresses of other creditors and the amounts owed.

File your interrogatories with the court. Once you've completed your interrogatories, take the original plus 2 copies to the clerk of the court that entered your judgment. You'll file your interrogatories using the same docket number as the original lawsuit. You may be charged a filing fee, typically less than $100. Call ahead to the clerk's office to find out how much the fee will be.

Have your interrogatories served on the other person. Once you've filed your interrogatories with the court, have a sheriff's deputy deliver them to the person you sued. You can also mail them using certified mail with returned receipt requested. If you mail your interrogatories, complete the proof of service form when you get back the green card indicating that the documents have been delivered to the person.

Wait for the person's response. Once they receive your interrogatories, the person has 30 days to send you written answers. If that deadline passes and they haven't responded, you can file a motion to compel. If the judge grants your motion to compel, they will enter an order for the person to respond to your interrogatories. If the person still refuses to comply, you can file a motion for contempt of court. The person will be arrested and held in jail until they comply with the court's order.

Getting a Writ of Execution

Request an abstract of judgment from the court clerk. The court clerk can prepare an abstract of judgment for you immediately after the judge enters judgment in your case. You don't have to wait until after any time for appeal. When the clerk gives you the abstract, review it carefully to make sure it includes all the information required by Texas law. It must have both your name and the name of the person you sued, that person's birth date and license number if you know them, that person's address, the docket number of the case, the date the judgment was rendered, the amount of the judgment, and the rate of interest.

File the abstract with the county recorder. Once you have your abstract from the clerk, you can take it to the county recorder of any county where the person you sued owns real property. Pay a small fee (typically less than $10) to have the abstract recorded, and it creates a lien on any property they now own or buy in the future. The judgment lien will be in effect for 10 years. If the property is sold or transferred, your lien must be satisfied through the proceeds of the sale. The judgment lien does not attach to the person's homestead, which is exempt. However, if they stop using the property as their homestead, the lien will attach. There is no limit on the number of counties where you can file your abstract. You technically could file one in every county in Texas if you so desired.

Request a writ as soon as possible. You can have the court issue a writ of execution as soon as 30 days after the judgment is handed down. The judgment is valid and enforceable for 10 years. However, it will go dormant and become unenforceable if no writ of execution has been entered. You can get form writs online, or you can have an attorney draft one for you. The fee for a writ of execution varies among counties, but typically is around $200.

Deliver your writ to the sheriff or constable. The writ instructs the sheriff or constable to take possession of any property the person owns in that county that isn't exempt. You can take your writ to the sheriff's department in any county where you believe the person owns property. If you sued an individual, you'll likely find that all or most of their property is exempt. A person's main residence and $30,000 ($60,000 for a married couple) in personal property is exempt. You'll fare better if you sued a business, since no business property is exempt. If the person has non-exempt property, the sheriff or constable will seize that property and sell it at the county courthouse. If the property is secured by a lien or mortgage, your judgment will be satisfied after that lien or mortgage is paid off.

Serve the person with notice of the sale. You must provide written notice of the sale to the person, either by mail or in person. If you send your notice through the mail, use certified mail with return receipt requested. You also must place a legal advertisement in the county newspaper of record that includes a description of the property to be sold and details regarding your judgment. Talk to an attorney or the court clerk to find out exactly what should be included in your advertisement and which newspaper you should place it in.

Follow up on the property sale. These sales occur on the first Tuesday of every month between 10:00 a.m. and 4:00 p.m., at the county courthouse where the property is located. You can attend the sale, but you're not required to go. Any proceeds from the sale of the person's property will go towards satisfying your judgment.

Invoke the turnover statute. If you are unable to execute on the property through the usual means of a writ of execution, you may use the courts to compel the person to turn over the property to the court for sale to satisfy the judgment. This law is unusual compared to other states, and invoking it can be complex. Hire an attorney who has experience collecting judgments specifically using this law. Unlike garnishment and execution, you can also recover attorney's fees if you invoke the turnover statute.

Getting a Writ of Garnishment

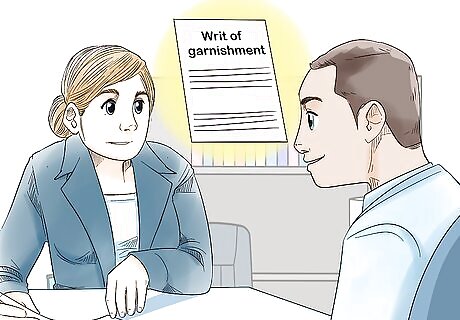

Consult an attorney. Getting a writ of garnishment requires you to file a separate lawsuit against a bank or other financial institution where the person has an account. Since garnishment law is complex, it can be to your advantage to hire an attorney to assist you. A writ of garnishment attaches to a bank account the person owns. Money can be taken from that bank account to satisfy the judgment, subject to some restrictions. Texas law prohibits the garnishment of wages for most debts, including judgment debts. You can attach a writ of garnishment to the person's bank account, but you cannot garnish their wages.

Identify the person's bank. To get a writ of garnishment, you must file a lawsuit against a third party, such as a bank, that holds the person's money. You may have gotten this information through post-judgment discovery. Other financial institutions where the person has an account, such as an investment bank or a retirement fund, may also be subject to garnishment.

File an application for a writ accompanied by an affidavit. You must file your application and affidavit in the clerk's office of the court that issued the judgment you want to collect. Bring 4 copies, because you'll have to serve the bank and the person who owes you. The affidavit states that to the best of your knowledge, the person does not have any property subject to execution that could satisfy the judgment.

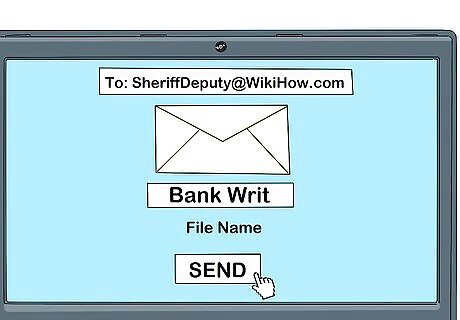

Serve the bank with the writ. Once the judge issues your writ of garnishment, you must have it served on the bank or financial institution where the person has an account. You can use a sheriff's deputy or send it through the mail using certified mail with returned receipt requested. Contact the bank to find out the name and address of the registered agent for service of process. This information may also be available on the bank's website. If you send it through the mail, you're responsible for filing a proof of service document with the court when you get the green card back showing the writ has been received.

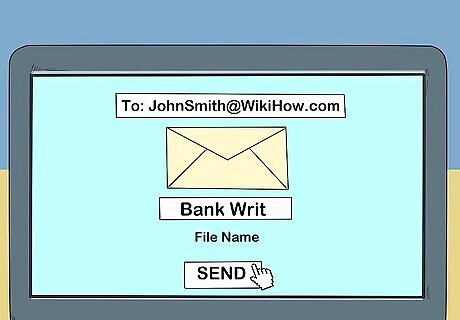

Serve the person you sued with the writ. As soon as you receive notice that the writ has been served on the bank, you must immediately serve the person who owes you the judgment. They have the right to intervene in the lawsuit, or they may go ahead and pay the judgment. Just as with the bank, you can serve the person using a sheriff's deputy or through certified mail. Don't forget to file your proof of service form with the court.

Wait for a response from the bank or the person. Both the bank and the person who owes you the judgment can file a written answer in response to the writ. If the bank doesn't hold any funds from the person, it can submit an affidavit attesting to this fact. The person has the ability to post a bond so they can recover the funds to which the writ of garnishment is attached. If the person owes the bank money, the bank may be able to offset your recovery. For example, if the person has a line of credit at the bank and is overdue on payments, the bank may state that the line of credit should be paid before your judgment is paid.

Attend any hearings as required. Depending on the number of individuals or institutions that become involved in your garnishment lawsuit, the court may have several hearings. Each party involved will have a chance to argue why they are entitled to the funds you've attempted to garnish. Even if you've handled the garnishment on your own up to this point, it would be wise to hire an attorney to represent you if the judge schedules hearings. Any banks or other financial institutions involved will have lawyers to represent their interests.

Comments

0 comment