views

X

Trustworthy Source

US Bureau of Labor Statistics

U.S. government agency that collects and reports labor-related information

Go to source

[2]

X

Trustworthy Source

National Conference of State Legislatures

Bipartisan, nongovernment organization serving the members of state legislatures and their constituents

Go to source

Advancing a Public Policy

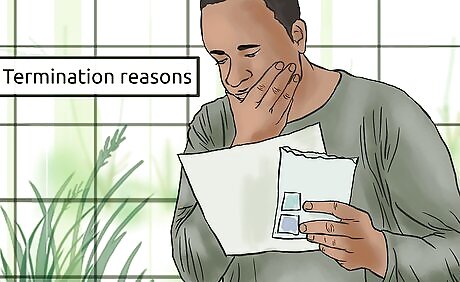

Evaluate your employer's reasons for terminating your employment. Under the public policy exception, employers cannot fire an employee for doing something that is in the public interest. Your employer also can't fire you for refusing to do something that would violate the law or undermine some public interest. It's not common for an employer to openly state a reason for terminating you that violates public policy – but it can happen. For example, suppose your employer has been sued after a customer slipped and fell. You saw a spilled drink, but you didn't have time to clean it up. Your boss tells you that in court you must say the floor was clean and dry, and that if you don't, you'll be fired. When you testify, you tell the truth about the spilled drink. The plaintiff wins his case, and you are fired the next day. Here, your employer directly stated that you would be fired unless you perjured yourself. Since perjury violates the law, it would fall within the public policy exception to at-will employment.

Look at the circumstances surrounding your termination. Although your employer may have fired you for a reason that was against public policy, they'll seldom say this straight out. However, putting the termination in context may provide clues as to the real reason for your termination. An employer may be motivated to get rid of you if you did something that caused them difficulties or cost them money – even if you were in the right to do so. For example, suppose you reported that your employer was violating health and sanitation regulations. Soon after a government inspection and investigation, you are terminated – despite the fact that you had several glowing performance reviews and were in line for a promotion. In that situation, your termination may fall within the public policy exception. You reported a violation of the law and were fired for it. This does not promote the common good.

Analyze the potential harm to the public. Not all cases that fall within the public policy exception are as straightforward as refusing to violate the law or reporting your employer for violating the law. Where your situation is more subtle, you still may have an argument that you fall within the public policy exception. For example, suppose you volunteer to be a crossing guard at the local elementary school. Although this duty doesn't cut into your scheduled hours, it does keep you from being able to stay overtime. People in your department regularly work an hour overtime each day, although it isn't mandatory. Your boss fires you, stating that you aren't a "team player" because you hold more value in your volunteer work than in staying at work with everyone else. In that example, you have a strong argument that your termination falls within the public policy exception. Our society encourages volunteers, particularly those who help ensure the safety and security of school children.

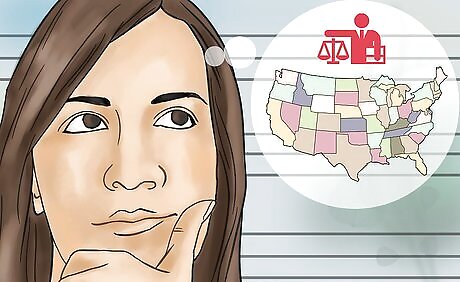

Make sure your state recognizes this exception. An overwhelming majority of states recognize some form of public policy exception to at-will employment. However, just because your state recognizes the exception doesn't mean your situation falls within the bounds of your state's law. There are only seven states that don't recognize a public policy exception at all: Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Maine, Nebraska, New York, and Rhode Island. Some states who recognize the public policy exception restrict it to very particular situations, such as a refusal to violate the law or being a whistleblower. Most states also recognize a public policy exception if you are exercising a legal right, such as filing a workers' compensation claim. In some states, you must be able to point to a specific state law that directly addresses the reasons for your termination. That may be a criminal law, or it may be state regulations that give you the right to do something or state that it is illegal to terminate anyone who exercises their rights under that law.

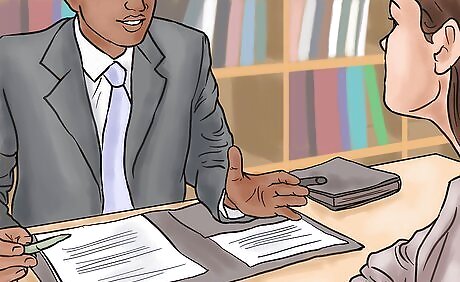

Consult an attorney. If you believe the reason for your termination falls within the public policy exception to at-will employment, seek legal advice. You may be able to sue your employer for wrongful termination. The best place to start your search for an employment attorney is the website of your state or local bar association. There you typically will find a searchable directory of attorneys licensed to practice in your area. Even if you're not sure whether you want to file a lawsuit, it's still a good idea to explore your options and find out whether you have a case. Many employment attorneys give free initial consultations. Take advantage of this to talk to several attorneys so you can find the one with whom you believe you will have the most productive working relationship.

Finding an Implied Contract

Get a copy of your employee handbook. Judges in some states have recognized an implied contract is formed through language in employee handbooks. Certain provisions, such as disciplinary policies, are most likely to create an implied contract. For example, your employee handbook may include a progressive discipline policy in which minor infractions are handled with increasing severity. Suppose your employee handbook states that you will be written up if you are late to work, and will be terminated after three write-ups. If you're terminated after only being late to work once, a judge might look at that as a violation of the implied contract in the employee handbook.

Review any direct communication from your employer. In the absence of written statements that apply to all employees, such as an employee handbook, your employer may form an implied contract with you personally. For example, suppose at your quarterly performance review, your boss says "We need more employees like you. As long as you're willing, there's a place here for you." If you were fired the next week, that sort of statement could be interpreted as creating an implied contract. However, keep in mind that some states have laws requiring employment contracts intended to last more than a year to be in writing. This makes these oral promises more difficult to rely on for legal purposes.

Look at your state's law. The implied contract exception is one of the more straightforward exceptions to at-will employment. However, while the exception is recognized in most states, it is deceptively difficult to prove. The exception itself is recognized in more than 40 states, so odds are you live in a state that accepts the idea of an implied contract in some form. However, this exception is extremely limited in many states. For example, the recognition of an implied contract in an employee handbook is not common and often controversial. Once a judge rules that language in an employee handbook creates an implied contract, that implied contract applies to every employee who was subject to the policies in that handbook. As long as your state recognizes the exception in some way, you can talk to an attorney about whether your particular case would fit within your state's understanding of the exception.

Talk to an attorney about what you've found. If you think you've found evidence that supports an implied contract, it's important to get an experienced employment attorney to evaluate your case. Since the law varies greatly among states, look for an attorney who is not only licensed in your state but has been practicing there for a number of years. These employment attorneys are most likely to understand the nuances of the implied contract exception to at-will employment within your state. Keep in mind that even if your case seems to fall within your state's exception, that doesn't mean that your case is particularly strong or that you're likely to win. Take advantage of free initial consultations to speak to several attorneys about whether you should pursue a wrongful termination lawsuit.

Implying a Covenant of Good Faith

Find out if your state implies a covenant of good faith and fair dealing. This exception implies a covenant of good faith and fair dealing in all at-will employment relationships. Essentially, it means you cannot be fired except for good cause. The good faith exception effectively guts the entire concept of at-will employment. For this reason, it is recognized by only a few states. To find out if your state is one of them, do an internet search for the name of your state followed by "good faith exception at will employment." You should be able to figure out from the short summaries of the top search results whether this exception is recognized by your state. Keep in mind that in many states that do recognize this exception, you must prove that your employer acted with actual malice. This means your employer terminated you because they wanted to harm you, damage your reputation, or put you at serious financial risk.

Look at the stated reasons for your termination. If your state recognizes the good faith exception, your employer essentially must give some reason you were fired. Without a valid reason, you could challenge the termination in court. It can help to compare the reasons for your termination to the policies and procedures set forth in your employee handbook. For example, you may have a stronger case that your employer violated the covenant of good faith if you were terminated for a reason that wasn't listed in your employee handbook. If you had a progressive discipline policy at your workplace and you were fired before being given the required number of warnings, this could be a violation of the covenant of good faith.

Consider the overall context of your termination. Even if the reason given by your employer may seem sound, it might not follow from the rest of your employment experience up to that point. A good indication of this would be that you were not expecting to be fired. If your termination seemed to come from out of the blue, look at any feedback you got from managers or supervisors before you were fired. Good performance reviews, a recent raise, or a recent promotion all are potential indications that your employer violated the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing.

Talk to others about the situation. Chances are if your employer fired you, you think it was unfair. Describing the situation to others can help you figure out whether you have a case that your employer was objectively unfair or out to harm you. You may already have had former coworkers express surprise and disbelief at your termination. Talk to them and find out if they know anything that you don't. Close friends and family members may not be the best people to help you assess the fairness of your situation. They will be biased towards you and may not be able to look at the situation any more objectively than you can. Instead, talk to acquaintances or people with whom you don't have any close emotional bond. They will be more likely to look at your situation objectively. If you're embarrassed to admit to an acquaintance that you were just fired, tell them you're asking for a friend.

Have an attorney assess your options. An experienced employment attorney is best able to analyze your situation. Given the difficulty of grounding your wrongful termination case on the good faith exception, legal representation is essential. Many state and local bar associations have an attorney referral service on their websites. By answering a few questions about your case, this service will connect you with attorneys licensed to practice in your area who take on cases similar to yours. Employment attorneys often give a free initial consultation. Schedule several of these so you can talk to more than one attorney to get a fuller picture of the strengths and weaknesses of your case. Pay attention to the attorneys and take their assessments seriously. If you talk to three attorneys and they all say your chances of winning are slim to none, it may be best for you to drop the matter. However, you might find an attorney who believes strongly in your case. If so, consider carefully whether filing a wrongful termination suit is worth the time, money, and effort.

Comments

0 comment