views

Developing Your Pitch

Create a basic outline. Even if you have no plans to write a full screenplay, a basic outline of your story not only allows you to develop an effective pitch but gives you written material that you can protect through copyright. Your outline can be as detailed or as skeletal as you like. Keep in mind that just because you include a particular fact or detail doesn't necessarily mean it will make it into a feature or television movie, if you end up selling your story. While your life is chronological, it may not follow the same lines a story would. Think about a story you've heard or a movie you've seen that had a good story line, and map your life story out along similar lines. A standard movie is broken into three acts, with the characters in the story following a similar trajectory. You may not think of the people in your life as characters, but in the movie of your life story they would be. Pull out episodes or events from your memory that will serve as a build-up to the ultimate climactic event. Those will make up the first act of your story. The climax will be the pivotal moment or event that provoked some sort of change, or from which you learned some sort of lesson. The third act of your story will encompass those events that draw together the climax and provide closure to the entire story.

Draft a synopsis. Once you have your outline, you're ready to write your synopsis, which is a one- or two- page document that you'll give to any producer who wants more information about your story after hearing your pitch. Think about a summation of the life story you want to tell in terms of how you would tell it to a friend with whom you were having a cup of coffee or a drink. The synopsis includes the entire story – the beginning, the middle, and the end – in a very brief way without a lot of details. Don't worry if you're not a strong writer – it's not as though the synopsis is going to be published. Simply focus on using active language to describe what happens in the story of your life. Write your synopsis in the third person, and strive to take yourself out of the story as much as possible and look at it from the standpoint of someone else who doesn't know you. Think about the aspects of your life that would be interesting or gripping to other people – those are the points you want to highlight in your synopsis.

Come up with a few loglines. A logline is a two- or three-sentence summary of your story that entices the person who hears it to hear the whole story and find out what happens. Writing a logline is something of an art, but there are some techniques you can use to create a strong logline that will sell your story. One way to think of a logline is as the punchline to a joke – only without the joke. This is a sentence or two that's going to tell the producers to whom you pitch what your story is about and what viewers ultimately should get out of it. Imagine if you overheard a punchline but never heard the joke itself. A good punchline would intrigue you and make you want to hear the joke so you could laugh along with everybody else. This is the same thing you're striving to do with your logline: make the producers want to see (meaning make) the whole movie. You can find examples of these sorts of summaries on many of the film sites online, such as IMDB or Rotten Tomatoes. Read the short summaries of movies you know to get a feel for the type of logline you can use for your life story. It can help to think about the genre of the story you're trying to tell – would it be a thriller, an adventure, or a romantic comedy? Your logline should be angled toward that genre. Keep in mind that some stories have elements of several genres, which would lend themselves to several loglines that emphasize each of those themes in turn. If you can't sell your story as a romantic comedy, for example, you might be able to sell it as a drama.

Protecting Your Rights

Consider consulting an intellectual property attorney. Even if you're not going to be doing a lot of writing or other creative work yourself, an intellectual property attorney can help you protect your rights and maximize your profits when selling your life story. Particularly if some event in your life has garnered local – or even national – media attention, you may have already received calls from people interested in buying your life rights. Under no circumstances should you so much as contemplate making a deal with someone to produce your life story without at least talking to an attorney. Not only can a good copyright attorney help you protect your rights before you start trying to sell your life story to a producer, they can review contracts and make sure you're going to get what you want and be fairly represented in any deal you sign. If you don't know any copyright or intellectual property attorneys, start your search on the website of your state or local bar association. There should be a searchable directory of attorneys licensed to practice in your area. Most bar associations also have an intellectual property section for attorneys who specialize in that area of law, so it's a good idea to focus on members of that section. Don't worry about trying to find a lawyer in L.A. or New York City (unless that's where you happen to live) – a local attorney will be easier for you to keep in touch with and may have lower rates.

Review life rights contracts. If you're not writing the story yourself but you still want to sell it to a producer, what you'll really be selling is your life rights. These agreements encompass a number of rights, but basically protect the producer from being sued by you for defamation or invasion of privacy. You can find examples of life rights contracts online, or if you've hired an attorney they may have a few samples to go over with you. Keep in mind that when you sign a life rights contract to sell your life story, this means the producer – or the writers or directors they hire – will have the right to change various aspects of your story if they believe it would make a stronger film. By selling your life rights, you lose the ability to sue the producer or anyone else associated with the film for defamation or invasion of privacy if you end up having problems or disagreements with the way your life is portrayed on film. These are serious issues that you should think long and hard about before you decide you want to sell your life story to a producer. While you may have some control over the story, in most cases you'll have to give up all rights or the producer will simply walk.

Register all written material. While you can't copyright an idea or a true story, you can copyright anything that's written down. Since a movie of your life isn't literally your life, you can copyright the treatment, synopsis, and any other written material you have. You can register your outline (also known in film circles as a "treatment") and synopsis for copyright protection by visiting the U.S. Copyright Office's website at copyright.gov. If you file your application online, copyright registration is only $35 and protects the words themselves as you've written them, as well as derivative works. This means no one can make a film based on your outline or synopsis without your permission, or you can sue them for copyright infringement. Keep in mind you can't sue anyone for copyright infringement in federal court unless you have a registered copyright. Since it's your life story, you may have a state lawsuit for invasion of privacy or defamation, depending on the content of the film. However, if you got significant publicity as a result of the events that are recounted in the film, you have a higher burden of proof that is substantially more difficult to meet than the burden of proof for private individuals. These written materials also can be registered with the Writer's Guild of America for a similar amount of money, which provides them with additional protection in the film community. While registration may be one of the simplest and cheapest things you do to protect your story, it also may turn out to be the most important – especially as you start sharing your story with producers you hope will adapt it for film.

Selling Your Story

Get significant third-party validation. Nearly everyone thinks something has happened in their life that would make a good movie or television show, and yet relatively few life stories are actually purchased by producers. Those that are typically already have demonstrated interest and popular appeal. Many movies or television specials based on true life stories happen because the producers optioned the film rights for a biography or autobiography that was already a bestseller. For this reason, it's almost always a good bet if you want to sell your life story to a producer to get it out in print first. A bestselling book may seem out of your reach, but you may be able to hire a ghost writer and put out a self-published book for a few thousand dollars. If a book seems out of your reach, you might want to look to local or regional interest publications to start garnering media attention for your story. Build a presence on social media and attract friends and followers with tales from your life that you'd ultimately like to see made into a movie. Keep in mind that producers ultimately are fairly conservative people when it comes to buying stories and making movies. The more you can demonstrate that there's already a proven demand for you and your story, the better chance you have of selling your life story to a producer.

Decide what you want your role to be. The markets you find and the producers to whom you pitch your life story are going to vary depending on what you imagine your future role to be in the production, and what skills you bring to the table. For example, if you want to write the screenplay, it might be a good idea to go ahead and get started. You probably will have better odds getting a producer to bite if there's already a script, even if it's one that will need a lot of work. If there are specific actors you imagine playing roles in the movie of your life story, you might want to consider getting in touch with their agents and getting them on board with the project first. It can be good to have someone "inside Hollywood" in your corner, not to mention the fact that actors often produce movies as well. Generally speaking, you'll have a better chance at selling your story if you've got something – whether that's a particular actor who's attached or a working screenplay – than if you've got nothing but an idea. If you want control over the movie or a final okay on the finished product, you probably will have to settle for less money in exchange. You also should keep in mind that producers typically will be reticent to have any significant degree of input from someone with little to no knowledge or experience in making movies.

Identify potential markets. Look at your story from the point of view of a producer, and find the elements that would attract those who create films or television shows of the genre where your life story best fits. For example, if you're a middle-aged woman who has gone through a harrowing or traumatic relationship or life crisis, you may want to try your luck with television networks such as Lifetime that frequently produce television movies based on true life stories. To find producer's names, look up films that are similar to the film you think could be made from your life story. Find out the production companies and the names of the producers, then search for ways to query them. You'll want to build a lengthy list of producers to whom you want to pitch before you start, because you have to assume that most, if not all, of them won't even respond to your initial pitch.

Send out your pitches. Find producers who have open calls for scripts or who are specifically looking for true life stories to make into movies or television shows. Start with them and draft a simple cover letter to introduce yourself. Never send a full script, or even a synopsis, to a producer or anyone else unsolicited. Thick packages containing scripts often will simply be thrown in the trash unopened, because no one wants to risk being exposed to the content and potentially ending up in a copyright infringement lawsuit because they produce an unrelated film with substantially similar elements. Introduce yourself in your cover letter, provide your logline and maybe another sentence or two about your life story – but that's it. The shorter, the better. Include a sentence or two describing the publicity you've received as a result of your story, either in the press or through a published biography. Close your letter by encouraging the person to whom you're writing to contact you if they're interested in hearing more, and then wait for them to come to you. If you have newspaper clippings, you may want to include a copy of one or two short stories to show the level of public interest in your story. Be prepared to send many of these letters out and never hear anything back from anyone. You may want to follow up by making a phone call or sending an email, but don't hound them. If you don't hear anything back, it's safe to assume they're not interested. Strike that name off your list and move on to the next one.

Selling an Option

Determine if an option is right for you. Most producers will purchase an option on your work instead of buying the product outright. When a producer purchases an option, they are purchasing the exclusive right to your life story for a specified period of time. During this "rental" period the producer will work to develop the product (e.g., creating a budget, getting actors lines up, getting a screenplay). Also, during this period, you will not be able to sell or option the rights to your life story to anyone else. Option contracts can be a great way to earn money without having to give up all the rights in your life story (unless the option is exercised). However, option contracts take your ability to advertise and sell your product elsewhere for a specific period of time. Some producers will purchase options on works to simply take them off the market so it can't be made by someone else.

Reach out to producers. Because most producers prefer to purchase options on life stories, try to find a producer who genuinely cares about the story you are pitching. Set up meetings with various producers in the industry and make your best pitch to each one. During your discussion, look for signs of the producer's genuineness. For example: See what plans the producer has for your project. Ask about the sort of budget the producer thinks is feasible. Ask for the producer's thoughts on casting. The more answers the producer has, the more serious they are about making the project a reality. Try to find out what other projects the producer has options on with a similar subject matter. If the producer already holds rights to a project similar to yours., they may want to purchase an option to shut your project down.

Discuss how long you want your option to last. When you find a producer interested in purchasing an option to your work, you need to decide how long the option will last. The option period should last long enough to allow the producer to do their due diligence on the project. However, you also want the option period to be short enough so you can keep shopping if you need to. In general, option periods are around one year. Most option contracts also include a provision allowing the producer to extend the option period for another year. In some cases, your contract might include multiple extension periods. A common option provision might state: "The option shall be effective during the period commencing on the date hereof and ending one year later (the “Initial Option Period”). The Initial Option Period may be extended for an additional six months by payment of One Thousand Dollars ($1,000.00) on or before the Initial Option Period expiration date."

Negotiate an option price. In exchange for the producer's exclusive right to develop and purchase your life story, the producer will pay you a sum of money called an "option payment". The amount of this payment will depend on whether there are competitive stories in the market place, whether you are represented by an agent, and the length of the option period. When you agree on an amount, it will be paid when the option contract is signed. This amount will either be folded into the purchase price (if the producer exercises their option) or will be separate. In general, the first option payment is often folded into the purchase price while subsequent extension payments are not. A common price provision may look like this: "In consideration of payment of One Thousand Dollars ($1,000), Writer hereby grants the Producer a six (6) month exclusive option to purchase all motion picture, television, ancillary and exploitation rights in and to the Property, in order to develop and produce an original motion picture based on the Property, provided that any sums paid under this Section shall be credited against the first sums payable on account of such purchase price."

Agree on how the option will be exercised. If the producer develops the project and wants to purchase the rights to your life story, they will need to exercise the contract's option. An option can be exercised in various ways including paying a purchase price or starting production. Your contract should lay out all the ways in which the producer can exercise the option. Your exercise provision might read: "Producer may exercise this Option at any time during the Option Period, as it may be extended, by giving written notice of such exercise to Owner and delivery to Owner of the Purchase Price."

Settle on a purchase price. One of the most important provisions in your option contract is the purchase price of your work. If the producer exercises their option to purchase your work, they will have to pay this negotiated price to you. In most option contracts, the purchase price is either a fixed price (i.e., $250,000) or a percentage of the project's budget (i.e., if the budget is between $500,000 and $1,000,000, the purchase price shall be $10,000).

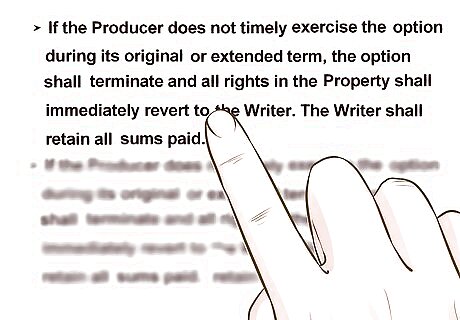

Make sure rights revert back to you. The last important piece of your contract will be your reversion rights. If the producer fails to exercise their option within the agreed upon time, you want to make sure all rights to the project revert back to you. Therefore, include something similar to the following in your contract: "If the Producer does not timely exercise the option during its original or extended term, the option shall terminate and all rights in the Property shall immediately revert to the Writer. The Writer shall retain all sums paid."

Execute the agreement. Once all the provisions of your contract have been negotiated, you both will sign the option agreement. At this point the producer will have the exclusive right to develop your project. You will not be able to sell or option the work to anyone else until the rights have reverted back to you.

Comments

0 comment