views

Identifying Lameness Problems

Check for behavioral signs of pain. Your horse may behave differently than they usually would if they're in pain. For example, a horse may become cranky when ridden, charge at jumps, refuse fences, or buck when they were previously mild-mannered. A change of character such as trying to bite an owner when grooming the back end, bucking, or general bad temper, can be a sign of pain. Your horse may also demonstrate pain during the tacking up process.

Consider whether or not your horse is working as hard as normal. Another common presentation is that the horse does not work to its full potential. It attempts to limit the discomfort by not exerting itself, which could mean it: Doesn't move as quickly or easily. Doesn't reach normal height when jumping.

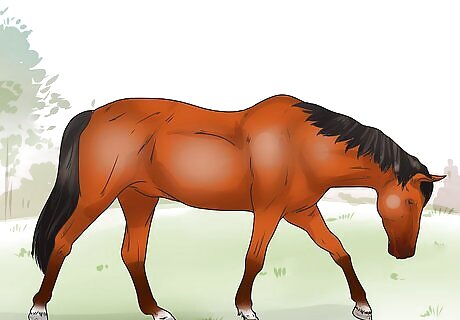

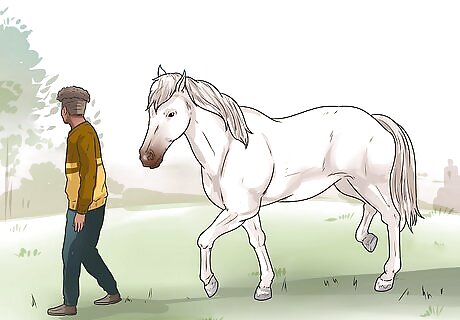

Notice if your horse begins riding heavy on the forehand. This phrase means that your horse tries to take weight off its hind quarters and shifts its center of gravity forward. When it does this it places more weight on its front legs and moves in a more labored manner because it takes more effort to lift its front legs. When riding the horse have a friend stand parallel to it and video its movement. Look for the horse lowering its head to counterbalance the back end. Look to see if all the legs are taking equal length steps or if one leg is taking shorter strides than the others. When riding the horse have a friend stand a safe distance behind the horse and take a video. Look to see if the hips move up and down symmetrically. A horse with a sore back leg will try to protect that leg with the result that the hip moves less.

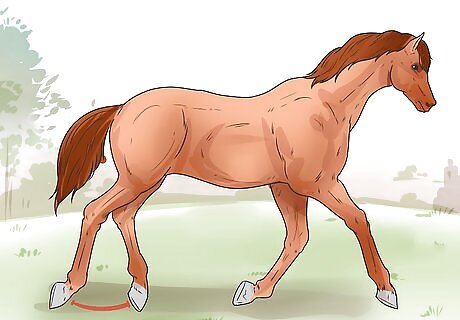

Take note if your horse is not engaging its back end. For fluid movement, the horse uses the power in its back end and bunches its hind legs beneath it to move forward. If the horse associates pushing off on its hind legs with pain it will be reluctant to do this, and will most likely move more slowly than normal. You may be able to feel this easily when you are riding your horse.

Keep track of your horse's ability to jump. Jumping requires the horse to shift its weight backwards and place a considerable extra load on its hind legs. If soreness or pain is present, it may try to avoid this discomfort by not fully using its muscles to propel itself upward. Your horse may lose height early, which means it will knock against jumps it used to take with ease. For example, you may notice that your horse knocks down fences during jumps.

Note any challenges your horse has with landing after it jumps. Landing after a jump involves tucking the hind legs beneath the body. This provides spring to push the horse forward onto its next stride. When your horse has a painful hind leg, it may slip and land awkwardly.

Look at the way your horse stands. Hock pain or general hind end discomfort alters the way a horse stands. It tends to shift its weight to minimize stress on the sore leg. Some things you might notice include: Resting one hind leg while standing. Standing with the sore leg tucked under its belly so that the hock is straight and the leg does not have any weight on it. Standing with one leg on a large mound of shavings to elevate it.

Assess whether your horse's gait has changed. Pain alters the way the horse moves, which is referred to as its "gait." Hock and back end pain tends to make the horse "mince" or take shortened strides with its hind legs. It transfers weight onto his forelegs, which gives him a hunched silhouette with its hind quarters tucked under and head carriage low. Because it hurts to flex the joint, the horse may not pick its leg up cleanly, and may have a tendency to stumble. A useful tip is to walk and trot the horse on sand so that you can trace its hoof prints. The sore leg tends to move towards the midline, rather than following the line of the matching front leg. If your horse's hock is injured, it may have a hard time walking backwards in a straight line. This is because the sore leg takes shorter strides, so the horse naturally moves in a curve to the affected side.

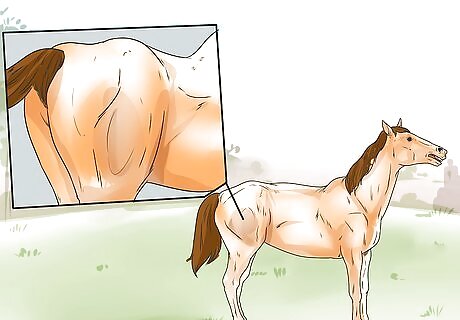

Watch for symptoms of disuse atrophy. If you notice that there is a loss of muscle mass over the thigh and hip of the affected leg, your horse may have a problem with its hock. This loss of muscle mass is a result of "disuse atrophy", which means that the horse has been protecting that leg and underusing it. When muscles do not get used, they can begin to waste away. Be aware that disuse atrophy can arise because of pain anywhere in the limb and does not localize the discomfort to the hock.

Contact a veterinarian to further the assessment. If you're sure your horse has a mobility issue, it is a good idea to call the vet to give the horse a thorough check over. A veterinarian can perform tests to isolate the source of your horse's pain to the hock. They can do a thorough lameness exam including flexion tests, nerve blocks, and X-rays if needed. The veterinarian will also look for other tell-tale signs of discomfort such as head bobbing, unusual foot placement, shortened strides, and weight shifts.

Localizing the Problem to the Hock

Look for signs of swelling. An injury to the hock, such as a sprain, causes the damaged tissues to release hormones such as histamine, prostaglandins, and bradykinin. These chemicals act on the blood vessels and make them leaky so that fluid pools in the area of the injury, causing swelling. This has a two-fold effect; the fluid helps isolate any harmful noxious substances from the general circulation, and the fluid is also rich in white cells to protect against infection. If in doubt that the hock is swollen, compare one back leg with the other. Look to see if the areas that normally 'go in' are puffy and baggy. Sometimes feeling the normal hock and then feeling the other side, can help you detect a difference in how they feel.

Check to see if the hock is hot. The inflammation of the hock generates heat. Because of this, you should feel along the hock. If the area feels hotter than other surrounding parts of your horse, your horse may have sustained an injury in the hock. Check the temperature of the injured hock compared to that of the hock on the other leg.

Ask your veterinarian to perform a flexion test. To perform this test, your horse's veterinarian will flex the hock joint and hold it in that position for about 1 minute. Then, they will release the joint and observe your horse's movement to see if their gait is different than before the test. Do not attempt to perform a flexion test yourself. Only a trained veterinarian should do this.

Have a vet perform a regional nerve block test. The idea behind this test is that if the pain in the hock is temporarily removed a previously lame horse should become sound. Only a veterinarian can safely perform this test, so do not attempt to do it yourself. During the test: The veterinarian first sterilizes the skin with surgical scrub, where the needle is to be inserted. A 1.5-inch needle, 20 or 22 gauge is used to inject about 1 ml of local anesthetic just below the skin along the path of the cutaneous branch of the superficial and deep fibular nerve. After the local anesthetic is injected the flexion test is best performed within 15 minutes, because the local anesthetic can spread to the lower limb making the foot numb which can also alter gait. If the lower limb becomes overly numb the horse may drag the leg and scuff the back of the hoof. If this happens the veterinarian will bandage the lower limb to reduce the chance of abrasions.

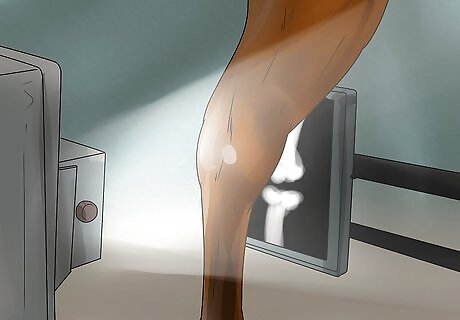

Consider getting a radiography exam done. If a flexion test and regional nerve block point to hock pain, then radiography is sometimes undertaken. Radiography is useful for detecting fractures, bony change (which occurs with arthritis), bone infections, bone cancer, and swelling of the joint capsule. To take the radiographs the vet will work with the horse in a standing position and use a portable x-ray machine. There are typically two images taken: an exposure at lateral view taken from the side (facing towards the horse), and an anterior-posterior view taken from in front of the hock joint facing towards the horse's tail. It is possible for x-rays to come back normal and yet there still be pain in the joint. This is because x-rays show bone damage, rather than inflammation of the joint lining. If the x-rays are clear but the hock is painful, this is a strong indication for giving a hock injections. Many veterinarians want to rule out chip fractures before giving hock injections, because the steroid could delay bone healing if this is the underlying reason for the lameness.

Comments

0 comment