views

X

Research source

Tragedies were meant to purge the audience of the negative emotions that build up inside of us through a cathartic release of those feelings.[2]

X

Research source

Studying classic tragedies and learning the finer points of writing fiction can help you write your own great tragic play or novel.

Studying Tragedy

Read classic tragedies. There have been many tragedies written throughout history, and each one reflects the time and place in which it was produced. Many scholars consider the epic works of Homer to be among the oldest examples of Greek tragedy, in which great heroes like Odysseus are faced with a series of misfortunes. But perhaps the most well-known tragedies are those penned by William Shakespeare, such as Hamlet or Julius Cesar, in which the hero almost invariably dies after tremendous suffering and misery. Greek tragedies tended to address a single topic and its plot, while English tragedies (including the works of Shakespeare) usually have multiple storylines that are tied together through shared loss and suffering. For a comprehensive collection of tragic works, consult your library, or search online. Many scholars and literary critics publish their own listings of what they consider the most important/influential works of literature.

Learn the basic characters. Though every tragedy is unique in its characters and plot points, there are some basic tropes of tragedy that tend to apply to all literary works in the genre. A tragedy generally involves either a tragic hero (often a person of great social importance), who suffers some great downfall and/or death as a result of some significant action or inaction, or the scapegoat (a person of low social importance), who is involuntarily thrust into tragic circumstances beyond his/her control. Most tragedies will have some or all of the following character types: protagonist - the lead character, who is almost always a tragic hero antagonist - any person or thing against which the protagonist struggles (often a villain, but not always) foils/counterparts - side characters, often associated with the protagonist or antagonist, who reveal or complicate some key aspect(s) of the main characters stock characters - often used to exaggerate or expand on some characteristic that arises in the rest of the tragedy narrators/chorus - not necessarily present in every work of tragedy, but an important part of certain works, often used to communicate directly with the audience

Analyze the tragic hero figure. Nearly every tragedy has a tragic hero at its center. In early Greek tragedies that hero was often a god, but as the genre grew the tragic hero came to include war heroes and even royalty or political figures. The general rule for tragic heroes today is that the character must be morally strong and essentially admirable to the audience. The tragic hero must experience some type of downfall (known as the "hamartia," or "tragic error"), often as a result of that character's hubris (often thought of as pride, though it also includes overstepping one's cultural/ethical limitations). The tragic hero usually experiences some sort of insight or recognition of his tragic fate (called the "anagnorisis"). At this point he knows that there is no going back, and that he must let the tragic fate before him play out. Above all else, the tragic hero should be pitiable. This is because he is destined to experience a downfall, and an audience would cheer or feel a sense of relief when a villain experiences misfortune. The true tragedy of a tragic work is that anyone could experience the sort of suffering that happens to the hero, and his downfall should purge the negative emotions of the audience.

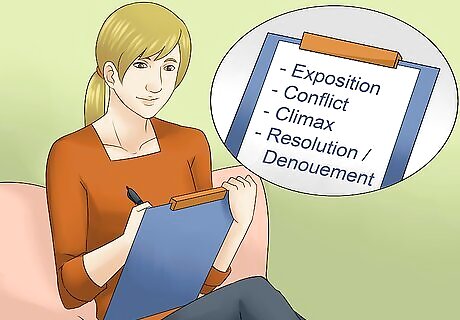

Study the tragic plot structure. Just as every tragedy will feature unique characters that fall into a standard "type," so each plot may be unique and original, while still falling into a common formulaic structure. The essential elements of every tragedy include: exposition - the essential "background" information, which may be delivered all at once in the beginning of the play or throughout the dramatic piece via dialogue and/or soliloquies conflict - the tension that arises as a result of some conflict, usually between either character vs. self, character vs. character, character vs. environment, character vs. natural forces, or character vs. group climax - the point in the play in which tension cannon be reversed and events must turn towards one of two outcomes resolution/denouement - the unraveling or release of tension, often through the death of one or more characters in the play

Understand the types of plot. The plot structure of a tragedy typically relies on one of three types of plot. Those plot types are: climactic - tension builds toward a single point (climax) before the resolution, usually through a linear structure comprised of causal actions episodic - often composed of numerous short, fragmented scenes involving many characters and numerous threads of action to highlight various aspects of humanity non-sequitur - inconsistent events involving existential, often under-developed characters engaged in something relatively meaningless, meant to highlight the absurdity of existence

Developing a Plot

Choose a mode of storytelling. Tragedies have traditionally been written and performed as plays. This dates back to the earliest tragedies, which were part of a Dionysian ceremony in which performers dressed as goats to reenact a hero's suffering or death. However, tragedies can also be written for a reading audience instead of a performance audience, which means novels/novellas and even young-adult fiction can all be classified as works of tragedy. Which mode of storytelling you choose will depend on both your areas of strength/comfort as a writer and the nature of the story you'll be telling. If you're equally experienced (or equally inexperienced) in both fiction and drama, try to choose a mode that fits your desired story. It may be easier to devise a storyline first without imposing the format of a play or a novel on your idea.

Come up with a story. Once you have a firm grasp on the nature of tragedies and their basic structural components, you'll need to create a basic outline of your plot. The plot of your tragedy will be the basic events and occurrences which will take place in your work. It should be about some basic idea, though ultimately the idea should come across through plot and character, rather than being simply "about" that idea. In other words, your story should mean something without coming right out and telling the audience what the story literally means. If you are basing your tragedy on an existing myth, you'll be somewhat bound to the events of that myth, and will not be able to significantly deviate from the main plot points within that myth without your audience losing interest. You may, however, be able to radically reinterpret a myth whose outcome is vague or ambiguous. Alternately, you may wish to create your own storyline from scratch, in which case you will not be bound by any canonical characters or events. Choose a plot that will help you tell the story you feel compelled to write. Don't think of the plot as a restriction. Instead, think of it as a lens through which you can write about some struggle or aspect of humanity.

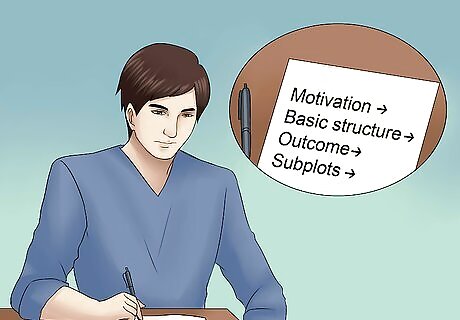

Outline your plot. Once you have a basic story idea, you'll need to outline the plot for that story. The easiest way to do this is to write out a few basic aspects of your story, so that you can further develop those aspects and arrange them into a coherent storyline. A good place to begin is by outlining the following parts of your tragedy: motivation - why the protagonist and antagonist do what they do in the story basic structure - the overall events that make up your story, and the sequence in which those events occur and/or initiate other events that will take place outcome - what will ultimately happen to resolve your story subplots - any sub-story lines you'd like to complicate your story or further challenge your characters

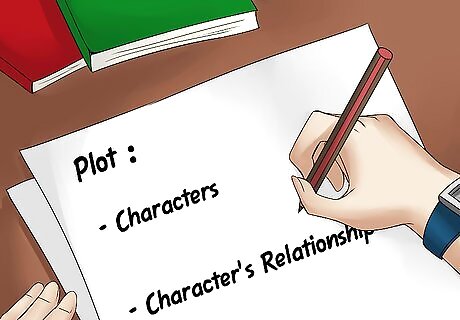

Create characters. Now that you've come up with a story and mapped out the basic structure of your plot, you'll want to create the characters who will act out your tragedy. You'll need the basic characters found in most tragedies, including a protagonist, antagonist, foil characters, and stock characters. At this point, you won't need to actually write dialogue for the characters, but you should be thinking about how they will play out on the page or on stage. You can keep track of these ideas by writing out a few sentences or a paragraph of notes on each major character. Think about what kinds of characters would fill the roles created by your story. Consider the relationships between each character. If they interact at all, or have any kind of knowledge of one another, they should have a clear and unambiguous relationship with one another. Common relationships typically fall into romantic, parent/child, sibling, friends, aggressor/victim, rival/adversary, boss/employee, or caregiver/receiver dynamics. Remember to include a tragic hero. At this point you should decide what his general downfall will be, and what choices he will make that will lead him to his fate. Consider making the characters question themselves, others, or their relationships with one another. You may also want to give them strong opinions, and use those opinions to further develop each character's personality and role. Your characters should be realistic and human enough to be likable and relatable, but because you're writing a tragedy, you may want to make one or more of the characters somehow superior to humans. This can take the shape of exceptional heroism, great wealth/power, or it could mean that one or more characters are actually super-human (gods/goddesses, magicians, etc.).

Writing Your Own Tragedy

Flesh out the plot. By now you should have come up with a basic premise, outlined the series of events that will tell that story, and created characters to enact those events. Once this is complete, you'll need to expand your plot into a full, functional story. Depending on where your strengths lie, this may be the easy part for you, or the extraordinarily difficult part of developing a story. Focus on the details. Details are what bring a story to life, but you also have to be careful not to weigh down your story with useless trivialities. When in doubt, think of the Chekhov's Gun principle: if you're going to include something (like placing a gun on stage), it must be relevant (for example, the aforementioned gun must be used in some significant way). Make things more complex. That could mean simply adding some type of plot twist, but a more effective way to complicate the story would be to develop something really interesting and compelling about some of the main characters. That way they become more three-dimensional and in turn more human - remember, no living person is ever as simple as they might appear in a character description. Think about the ways in which each character changes throughout the course of your tragedy. If any of the main characters emerges unchanged (other than, say, a villain who will never feel remorse for his actions), your tragedy is not developed enough. Let your characters be emotional. Don't make them unrealistically emotional, but ensure that as they suffer on the page, their suffering is apparent and acknowledged by the audience.

Develop the tragic hero's downfall. You should already have a general idea of what will happen to the tragic hero and what series of events will lead to his fate. But as you go through the process of writing your tragedy, you should expand on that series of events and weave elements of the hero's demise throughout the book or play. This is the central element of a work of tragedy, and it requires consistency throughout the manuscript and sufficient time to develop and unfold on the page (or on stage). If the hero's tragedy involves revenge, the reader/audience should understand the reasons for that revenge from the first few scenes or chapters. For example, in Shakespeare's great tragedy Hamlet, the audience is introduced to the ghost of King Hamlet in Act One, Scene One, and knows that his death will be a significant aspect of the play that follows. All of the important characters who are relevant to the hero and his downfall should be introduced fairly early on in the tragedy. The play/novel should begin by giving expository information or contextual clues to explain the hero's situation, and should begin setting up the hero's rise to hubris and eventual downfall from the very start.

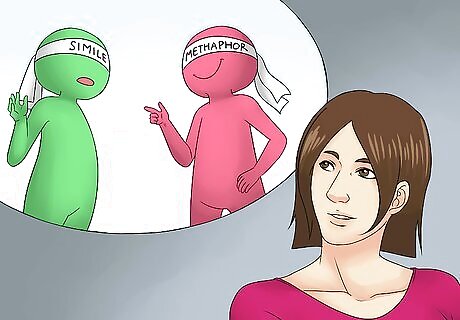

Incorporate simile and/or metaphor. Simile and metaphor have historically been tremendously important to any successful tragedy. They give further meaning to the words on the page or the actions on the stage, and they allow the reader/audience to feel involved in the story by deciphering your comparisons and reading into the "bigger picture" of your work. Metaphors are comparisons between two things, while similes compare things using the words "like" or "as". All similes are metaphors, but not all metaphors are similes. An example of a metaphor would be, "Her eyes shine into mine." The reader knows that a character's eyes do not literally emit light, and it's clear the author meant that a character has bright, captivating eyes. An example of a simile would be, "As she cried, her eyes glistened like stars." Again, the reader knows that the character's eyes are not literally similar to a celestial body, but simile and metaphor both lend a poetic quality to the language used in a piece of writing.

Create scenes. Scenes are the bread and butter of a tragedy. They are the framework in which everything happens, and each scene should have a clear beginning, middle, and ending that also contributes toward the overall storyline. Every scene should have a basic buildup, action, climax, and resolution/wind down.

Build tension. As you expand on the plot, if you find yourself wondering whether the plot is meaningful enough, think about ways to raise the stakes. For example, if someone is afraid that her husband will be kidnapped and murdered, make it clear to the reader why that would be tragic. Has she lost someone important to her in the past? In the world you've created, would she be able to survive as a widow? All of these questions will make a difference between the audience thinking "That's unfortunate that her husband died" and "This is a tragic event that will probably lead to her own death." Tragedies are full of horrible, disastrous events. Make it clear that the upsetting things that happen to your characters are horrible beyond the surface-level shock.

Resolve the tension. Just as every action must have an equal reaction, every tragedy's tension must have a resolution. You simply cannot leave critical events unresolved or end a tragedy without everyone's lives changing (usually by falling apart) in some way. All loose ends must be resolved, anything set in motion during the tragedy should come to pass, and the horrible things that happened in the play should lead to meaningful suffering/loss/death. Let the resolution of tension lead into a natural ending place for the story. The plot will suffer if the story continues for any significant length after the tension has resolved, because there will no longer be any stakes driving the story or affecting the characters.

Revise your work. Like any piece of writing, your tragedy will need to undergo a revision or two once it's finished. This may entail providing further details to develop a character, filling in plot holes, and adding/removing or re-writing scenes as needed. You can revise the manuscript yourself, or ask someone you know and trust for an honest evaluation of the manuscript. Give yourself two to four weeks after finishing the manuscript before you attempt to revise it. It can be difficult to distance yourself from your work after only a few days, and because the story is still fresh in your mind you may overlook certain things that wouldn't make sense to an outside reader. Try doing a read through before you sit down to make any actual changes. Just take notes on any sections that are confusing, underdeveloped, or unnecessary/irrelevant without stopping to revise. Then you can decide how to remedy those issues once you've gotten all the way through the manuscript. As you read and revise, ask yourself whether the story makes sense as a whole, whether the plot is compelling/engaging, whether it flows smoothly or feels choppy, and whether the stakes are high enough for the characters involved to elicit an emotional response from your readers/audience. Think about the impact the final product will have on your readers/audience. Remember that the tragic hero should be a likable character with good, desirable qualities whose demise results from his/her own choices, whether those choices are actions or inactions. Will your hero's downfall ultimately cause the readers/audience to feel pity and fear? If not, you may need to make significant revisions to your manuscript.

Edit at the line-level. Once you've hammered out the larger issues within the manuscript during the revision stage, you'll need to do a thorough editing of the entire work. This may include checking spelling, ensuring subject-verb agreement, correcting for tense agreements, and taking out any "filler" portions of the manuscript. Make sure that the way you choose your words and phrase your sentences is precise and meticulous. Cut out any unnecessary words ("filler"), confusing words/terms, and poorly-constructed sentences. Avoid repeating the same words needlessly. It comes across as sloppy or weak. Instead, find new and interesting ways to say what you're trying to say. Resolve any run-on sentences and any sentence fragments in your work. These can be confusing for readers/audience members, and may be difficult for actors to speak.

Comments

0 comment