views

Dr Mark Mobius, executive director, Templeton Emerging Markets Group, tells Pravin Palande and Shishir Prasad that he is optimistic about India and in many cases, a weak rupee may actually benefit some companies in the country.

Dr Mark Mobius

Profile: Executive director, Templeton Emerging Markets Group

Career high point: Consistently voted as one of the most influential investment managers in the world

Last vacation: Doesn't take any

Known for: Travelling a lot; comic book based on his life

The idea of a single currency (euro) for differing political units seems to be in trouble. What does it mean for global currency markets?

The euro, which entered circulation in 2002, is now the second-largest reserve currency as well as the second-most traded currency in the world after the US dollar. However, dropping out of the euro zone was sometimes cited as an option for some European economies during the region's recent sovereign debt crisis. Of course, there are challenges, such as member countries need to control government spending, but once these are sorted out, I believe the euro should be very successful and, in fact, it could possibly play a greater role in the global economy in 2020 than it does today. We are very positive on the euro, and think more countries should consider joining the EU.

How do you look at Europe in the coming year? Do you think countries like Greece will be allowed to move out of the euro? Will this not affect Germany and France? Will this problem have an everlasting effect on the world and especially on countries like India and China?

Some time ago, we had currency experts suggesting that countries like Latvia and Estonia should adopt the euro as they had sufficient currency reserves to do so. And on January 1, 2011, Estonia did indeed officially adopt the euro. I am very positive on the euro, and I think more countries should consider joining the EU. For those who recommend that Greece or some other country be thrown out of the euro, it is important to realise that it is not a choice any government or multinational body can make. The Greek people will decide what currency they want to use.

Recently, I was in Zimbabwe where they suffered from thousands of per cent inflation and their local currency was devalued so greatly that to purchase a loaf of bread required billions of Zimbabwe dollars. Now they are using the US dollar. When I asked a Zimbabwe banker: "When did the government decide to abandon the local currency and adopt the US dollar?" He replied: "The government did not make the decision, the people make the decision." That is the case with the euro. It is doubtful that the Greeks or any other European country's people would want to abandon the euro to go back to their former currency.

Will the European sovereign debt crisis mean that global markets will look at sovereign indebtedness differently in the future? What does it mean for finance ministers of emerging economies? Will international investors prefer countries with moderate growth but low indebtedness in the future?

Greece, Spain, Portugal and Ireland continue to have problems managing their debt. While they obviously do not want to default, just by looking at the numbers, I think it may be quite difficult for them to avoid it. The question now is how they can continue to instill confidence back into the markets and how they might restructure their debt or raise more debt to repay the old debt. That said, I believe the governments in these countries continue to be very focussed on coming up with a constructive approach to restructuring their debt obligations, and in working with the European Union to try and avoid large scale problems.

The debt crisis in the US and Western Europe actually puts emerging markets in a very strong position because emerging markets' debt to GDP ratios are much lower than developed countries, and their foreign reserves are greater than the developed countries

What is your view on India's policy to increase interest rates 13 times in 12 months to control inflation?

The RBI (Reserve Bank of India) had maintained an anti-inflationary stance given the inflationary situation in India. While the central bank has recently indicated a short-term pause, the medium term policy direction will depend on how various factors pan out — inflation, global liquidity/risk appetite, capital flow trends, fiscal deficit and global commodity prices.

Given that the trends in food inflation are being increasingly driven by structural factors, the government needs to address the bottlenecks for a longer term solution. Globally, many central banks have now started to focus on boosting liquidity and growth — in India, we expect short-term rates to fall faster than long-term rates (due to uncertainty about government borrowings).

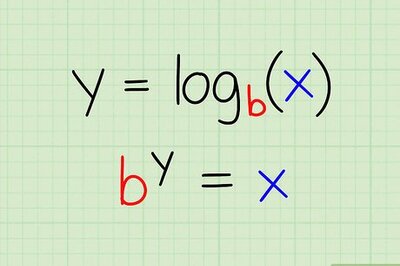

Indian rupee is down by 13 per cent over the last three months. How do you look at the prospects of the Indian rupee in the long run?

A weak rupee makes the government's job of containing inflation significantly more difficult, but it also makes India more competitive in the global landscape and therefore we should not be too alarmed. Some companies will be negatively impacted while others, like exporters, would benefit from higher foreign earnings.

In general, the scenario for the rupee is very mixed in view of the fact that foreign reserves in India have been healthy, but the balance of payments continues to be negative as is the budget balance. The depreciation against the USD from about Rs 40 to Rs 50 has come despite decelerating money supply and high interest rates. In view of the above factors, the only way to stop the continuing weakening of the rupee would be for foreign investment flows to increase into the country.

The government and the RBI announced measures like enhancing FII (foreign institutional investors) investment limits in government and corporate bonds by $5 billion each, increasing deposit rates for Non-Resident Indians and easing overseas borrowing norms for local companies to encourage dollar flows in India. With regards to portfolio flows, general weakness in global equities and the fact that the Indian market is somewhat more expensive than other emerging markets, could inhibit large flows into the country.

Comments

0 comment