views

“Suddenly there was crazy movement of soldiers outside. We thought war had broken out. Then there were also rumours of clashes on social media, which were rubbish. We would have heard the gunfire and bombs going off had that happened because we are so close to the border,” says a resident of Kupup, one of the last villages near the Indo-China border.

This area was tense in the initial days, but fears have slowly ebbed and there was never any restriction on their movement.

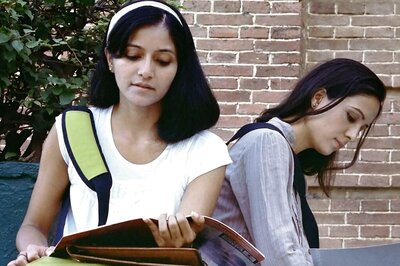

The initial media hysteria post the India-China standoff has residents edgy. They are not comfortable talking to reporters. They share a close working relationship with the army and don’t want to jeopardise it.

“Even we have not seen Doklam, we are not allowed to go to that area. How can reporters stand 80 km away and say they are at ground zero,” says another resident unhappy with the reports.

The area has been sealed off by the army; barring soldiers and their support staff no one is allowed in the area.

Reliable sources in the army tell us that soldiers from both sides stand face-to-face 24x7 at over 11,000 feet in Doklam braving the elements.

The monsoon rains lash the plateau and night temperatures can drop below 5 degrees. Shifts change and wet uniforms have to be dried out, but with no sign of the sun for days it’s an arduous task.

Several kitchens have been set up to feed the hungry jawans. The Chinese and Indian soldiers posted there see other each other every day and some apparently even exchange cigarettes.

On our first attempt to travel to Kupup, Nathang and Zuluk villages, we got as far as Thegu, which is approximately 15 km from Nathu La.

The army checkpoint seemed to know we were coming. The sentry was quick to reach out to his superiors. As I waited for them to check our credentials, I walked around.

A small poster remembering the martyrs of the 1967 skirmish is testimony to how volatile this area can be. On that fateful day, men of the 70 field coy engineers assisted by 18 Rajput were laying wire fence when Chinese opened machine gun fire on them. Caught in the open, 70 of our soldiers were martyred.

“Two brave officers Captain PS Dagar of 2 Grenadiers and Major Harbhajan Singh of 18 Rajput rallied a few troops and immediately assaulted the Chinese medium machine gun position however both of them died a heroic death (sic),” reads the citation.

At 13,000 feet, Thegu also boasts of the world’s highest working ATM, but we were not able to use it as we were turned back. The officer asked us to try from Zukuk village, the southern approach to the border villages.

On our way back, we stop at Tsomgo (also called Changu) lake. Located at a height of about 12000 feet, it is one of the star tourist attractions. This is off-season so only a few shops are open. We stop by at one of them and start chatting with the shopkeeper, a young man in his twenties as he prepares Maggi for us.

“I have come back after 20 days to look for two of my Yaks which have gone missing,” he says. “I would not have come back because there is no business. First there was the Gorkhaland strike and now this. How will tourists travel?”

We pay and leave; we could possibly be his last customers before the next season in October or till the situation improves.

A few kilometers below Tsomgo Lake, the acclimatisation centre for Kailash Mansarovar pilgrims lies deserted. This year the yatra was cancelled by the Chinese following the standoff.

On our way back, a nervous military policeman stops us at another checkpoint. “Where did you guys vanish? From Thegu it takes only 20 minutes to get here,” he asks.

We laugh and say we were eating Maggi. He then proceeds to check our cameras to delete any sensitive videos and even takes a picture of my video journalist with his mobile phone.

This place is teeming with selfie-taking tourists every season, search google and you will find every angle possible. The standoff had suddenly turned a tourist destination into a top-secret military installation.

In Gangtok, I meet a group of young entrepreneurs who are in the hospitality business. This has been a bad year, first the highway liquor ban, and just when the tourist numbers were peaking, Darjeeling hills went into turmoil with the Gorkhaland movement.

“We are more worried about Gorkhaland than the Chinese. Wish the Centre would intervene and solve the problem. Our businesses are suffering,” says Tashi, a young restaurant owner.

His friend, a hotelier, disagrees, “A war with the Chinese could spell doom for us. I am more worried about them than our own people fighting for statehood.”

We are off again to Zukuk via Rongpo, the gateway into Sikkim.

At Zuluk we meet Gopal Pradhan, an entrepreneur who transformed this sleepy hamlet into a tourist destination. This is the old silk route to Tibet, close to the site of the current standoff.

Gopal Pradhan is agitated with the hysterical reporting. “You can see there is no problem here and everything is peaceful. Why do media report as if a war is starting tomorrow? I saw a journalist who was pointing at my village and saying that’s Bhutan. Even I have never been to Doklam and I have lived here all my life. Why lie?”

The military checkpoint at Zuluk is once again prepared for us. They point at my video journalist and call out his name, “You guys are from CNN-News18,” they gleam with pride on having ‘exposed us’. They take away our identity cards, check our mobile phones for suspicious footage and finally deny us permission.

Back in Gangtok, we meet a businesswoman who travels via Nathu La to Tibet to trade. They form a miniscule percentage of the $70 billion bilateral trade between the two countries.

“Some people are saying don’t buy Chinese. I guess even that decision will be good for the country,” she says laughing.

Comments

0 comment