views

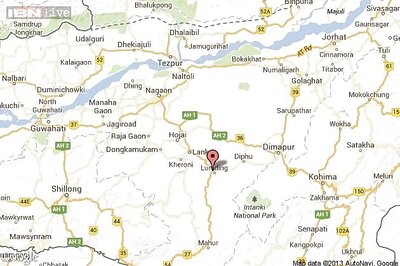

Tokyo: The Daiichi nuclear power plant in Fukushima is built on the shoreline in northeast Japan. So when an 8.9 magnitude earth quake struck on Friday, the tsunami waves it spawned - as tall as a house and speeding like a jet plane - washed right over the reactors and put them at risk of a meltdown.

Engineers were dousing the plants with seawater in a desperate effort to prevent a calamity on Sunday, even as the government evacuated 140,000 from the area after radioactive steam was released from the stricken plant.

The nuclear crisis was a triple whammy for Japan, coming on top of the earthquake - Japan's biggest and the fifth strongest ever recorded in the world - and one of the most powerful tsunami in history, which caused scenes of unimaginable destruction in northeast Japan.

Japan's Prime Minister Naoto Kan said the country was facing its biggest crisis since the end of the Second World War, which was when the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

"We're under scrutiny on whether we, the Japanese people, can overcome this crisis," a grim-faced Kan told a Sunday night news conference.

The quake caused Japan's main island to shift 2.5 meters (8 feet) and moved the earth's axis 10 cm (2.5 inches), geologists said. The question now is whether the catastrophe will spur other seismic changes in Japan, which has yet to emerge from its "lost decades" of stagnant growth, ageing population, and loss of international prestige following the collapse of the Japanese asset bubble in the early 1990s.

At the very least, the drama at Fukushima is bound to shake the faith of many Japanese in the safety of their nuclear plants. The catastrophe will also sorely test Kan's deeply unpopular government.

Kan flew over the stricken nuclear plant and quake-hit areas on Saturday morning after ordering an evacuation in the area, borrowing a military camouflage jacket with the name tag "Miyamoto".

"I came to realise the huge magnitude of damage the tsunami has wrought," he told reporters on his return to Tokyo.

If any country is prepared to cope with an earthquake, it is Japan.

Earthquakes are a way of life in Japan, occurring on average every five minutes. Buildings by law are erected to withstand violent tremors. As office towers shook violently in Tokyo on Friday, people grabbed helmets and dove under their desks, hoping their quake-resistant buildings could withstand the damage. Schoolchildren are drilled on what to do when a quake hits. Many households have survival kits.

But this quake was on a completely different scale, and left the country of 127 million people dazed and bewildered.

The tsunami, a Japanese word meaning "harbour wave", surged through towns and cities, bulldozing everything in its path. A large freight ship was sitting incongruously in the streets of Kesennuma in hard-hit Miyagi prefecture. A wrecked airplane lay nose-deep in the rubble of homes in the port of Sendai.

"Is it a dream? I just feel like I'm in a movie or something," said Ichiro Sakamoto, 50, in Hitachi city, around 129 kms (80 miles) north of Tokyo, where fishing boats were tossed far inland by the series of three tsunami waves.

A multistorey building stood alone in a vast wasteland after the tsunami waves roared through the small coastal town of Rikuzentakata. Cars were piled atop one another, train carriages tossed carelessly aside.

About 10,000 people were feared killed by the earthquake, and as many as 20,820 buildings were either destroyed or badly damaged. The death toll could go higher. Local governments had lost contact with tens of thousands of people, Kyodo said.

Millions of people were spending a cold night on Sunday without water, electricity, homes or heat.

Survivors huddled under blankets in Rikusentakata. Others stood in front of posters with a list of the dead and missing, some weeping. Many of them were middle aged or elderly, reflecting Japan's rapidly ageing population.

Kazuaki Sakai, 70, said he watched from a hill as the tsunami waves roared into the town.

"First the sea pulled back so much that I could almost see the bottom. About 10 minutes after the quake the first (wave) hit and pulled back, and then the next wave hit about 10 metres high, completely black, making a whirlpool. Then that one pulled back and I could see the (sea) bottom again. That repeated for about 10 times in about a half-hour."

Michiko Yamada, 75, said she ran to the rooftop of a hospital and stayed there for 12 hours with her husband in complete darkness. "I ran away with what I'm wearing, barefoot. It was truly cold," she said at a middle school shelter in Rikuzentakata. "I don't have anything now. No money, no house. We built that house nicely just five years ago. I'm on way now to borrow socks from my relatives."

A 60-year-old man was found floating on a piece of roof about 15 km (9 miles) offshore from Fukushima prefecture. Hiromitsu Shinkawa was airlifted and in "good condition" after being swept out to sea with his home, Kyodo said.

A humanitarian relief operation of epic proportions was under way. The government was preparing to double to 100,000 the number of Self Defense forces being mobilized along with police, the Coast Guard, and disaster response teams.

The United States has sent nine warships with humanitarian aid, led by the aircraft carrier USS Ronald Reagan, underlining the close military ties with its Pacific ally.

The tsunami swept over a vast area of rural Japan, destroying an untold amount of rice paddy farmland. This could accelerate changes in Japan's politically powerful farm sector, which enjoys tariffs in excess of 700 per cent for polished rice. The government has been pushing to reform a farming sector that makes up just 1 per cent of the economy by giving them greater scope to lease land to companies.

Japan is likely to suffer a temporary economic hit and then enjoy a boost from reconstruction, analysts said.

That certainly was the view of Prime Minister Kan, who said on Sunday the calamity will create huge demand in the process of reconstruction, and urged people not to be "pessimistic" over the economy.

Japan will have a New Deal-like" economic recovery, Kan said, referring to the Depression-era programmes of US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

But the cost of rebuilding will also worsen Japan's already worryingly high public debt burden, the largest among advanced economies, double the size of its $5 trillion gross domestic product.

While few expect the economic damage to exceed that of the Kobe earthquake in 1995 when the economy shrank by two per cent before rebounding, the concern is that Japan's economy is much weaker today. Additionally, some economists said the scale of the disaster and its consequences remained far from clear, especially with the nuclear plants at risk.

"Not since the Cold War have I been asked to think about the economic consequences of a nuclear explosion in a densely populated area in a modern industrial economy," said Carl Weinberg, chief economist at High Frequency Economics in New York. "I don't relish that task."

The Kobe earthquake in January 1995 struck one of the most populated and industrialized regions, killing 6,434 people and causing damage estimated at around $100 billion.

Takuji Okubo, chief Japan economist at Societe Generale in Tokyo, noted that Japan's economy grew by 1.9 per cent in 1995 and 2.6 per cent in 1996, above the country's trend growth rate at the time of 1.5 per cent. Private consumption, government spending and, especially, public fixed investment all grew above average in 1995 and 1996, Okubo said in a report.

As for the world economy, Japan is not a major engine of global growth so the disaster poses less of a risk to other countries than soaring oil prices caused by turmoil in the Middle East and North Africa.

"The global economy will be fine," said Stephen Stanley, chief economist at Pierpont Securities in Stamford, Connecticut.

Hopes surfaced the disaster could end the debilitating political warfare that has prevented the government from crafting policies to cope with a bulging debt and fast-ageing society.

But pessimists said chances were slim that rivals to the unpopular prime minister inside and outside his own party would keep off the gloves for long. Opposition parties are pressing the premier to call a snap election they think they could win, while critics in the ruling party want him to resign to improve their own chances.

Kan is already Japan's fifth leader since 2006.

"Kan's government avoided a crisis due to this huge disaster," said independent political analyst Minoru Morita. "As long as media are reporting only about the disaster, Kan's government will be stable," he said. "Once the news returns to normal, criticism will emerge again."

Kan will have his hands full as well dealing with critics of Japan's nuclear policy.

The 40-year-old nuclear reactor facing a possible meltdown in Fukushima was originally scheduled to go out of commission in February but had its operating license extended another 10 years.

The stricken No. 1 reactor operated by Tokyo Electric Power Co's Fukushima Daiichi power plant is the utility's oldest atomic core and was originally scheduled to operate only 40 years.

But the Japanese government's Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency approved TEPCO's application to keep it hot after inspecting the facility, according to a statement on the Ministry of Trade Economy Industry's website (www.meti.go.jp/english/index).

TEPCO has had a rocky past in an industry plagued by scandal. In 2002, the president of the country's largest power utility was forced to resign along with four other senior executives, taking responsibility for suspected falsification of nuclear plant safety records.

A few years later, it ran into trouble again over accusations of falsifying data.

Engineers worked desperately to stop fuel rods in two damaged reactors from overheating after some controlled radiation leaks into the air to relieve pressure. The fear is that if the fuel rods do not cool, they could melt the container that houses the core, or even explode, releasing radioactive material into the wind.

The government said there might have been a partial meltdown of the fuel rods at the No. 1 reactor.

The fallout from the Fukishima nuclear plant accident could well give fresh momentum to opponents of nuclear energy. The industry in the United States has never really recovered from the Three Mile Island mishap in 1979.

Japan is one of the giants of the world nuclear industry, producing almost 30 per cent of its electricity from the source. Ambitions to boost this to 50 per cent by 2030 may now be called into question.

That could have global implications. Growing world hunger for energy is already straining supplies. By 2030 consumers and businesses worldwide will be gobbling up 35 per cent more energy than in 2005, according to Exxon Mobil.

Moreover, with solar and wind power yet to be economical and scalable, the nuclear industry is the biggest source of low carbon electrical energy.

"The public demands nothing less than perfection from the nuclear industry in terms of safety," Reuters columnist Christopher Swann wrote. "That's particularly true in Japan, the only nation to have endured a nuclear attack. Fear of radiation is deep-seated in the country - just look at its great cinematic export, Godzilla movies. So a minor lapse could prove a big setback - one that makes meeting the world's voracious demand for energy look still more intimidating."

Comments

0 comment