views

Delhi loves politics just like cricket. How else could one explain the excitement on the city roads about the April 23 municipal elections, right after the tiring, two-month long political slugfest in five states? Municipal polls are also interesting because local issues often overpower the wider narrative, making things unpredictable. When it comes to a complex metropolis like Delhi, the issues determining local elections change not only from constituency to constituency, but sometimes from street to street.

Delhi loves politics just like cricket. How else could one explain the excitement on the city roads about the April 23 municipal elections, right after the tiring, two-month long political slugfest in five states? Municipal polls are also interesting because local issues often overpower the wider narrative, making things unpredictable. When it comes to a complex metropolis like Delhi, the issues determining local elections change not only from constituency to constituency, but sometimes from street to street.

“E-rickshaws have taken away most of our customers,” says Syed Jawaid, who has been driving an auto for 20 years and is most vocal among the 15 odd auto drivers awaiting passengers. “Can’t the government clear the road? It takes us 45 minutes to go to the nearest Metro station, a ride which should not take more than 10 minutes,” he says.

The term ‘government’ here could mean the state government, the Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD) or the Delhi Police that play different yet sometimes overlapping roles in administering the civic infrastructure.

“Delhi is a classic model of how not to govern. The city’s civic infrastructure has been thought through in patches,” says Yogendra Yadav, academic-turned-politician and co-founder of Swaraj India. “Hunger is not the problem for Delhi’s poor, but they have to pay more than the rich for basic services.”

In Delhi’s maze-like governance model, people get confused over who is responsible for which civic service, leading to public ire. “We autowalas helped the AAP win Assembly elections in Delhi, but they haven’t stopped the police from harassing us,” says Jawaid, who lives in nearby Tughlakabad Extension. When a fellow auto driver tries to explain to Jawaid that the Delhi government has no control over Delhi Police, he says, “How can they not do anything when they have full majority?”

Another auto driver pointed out that there are not enough auto stands in the city, forcing them to halt on the roadside, leading to penalty. “Sometimes cops ask us for Rs 2,000 bribe, otherwise they seize the vehicle. It’s nearly impossible to get a commercial driving licence in Delhi without paying up to Rs 30,000 to the middlemen. Most auto drivers don’t own the vehicle and have to pay Rs 300 a day as rent. After all this, we earn Rs 500-700 with 10 to 12-hour work a day,” he says.

“Every monsoon, Sangam Vihar gets flooded in waist-deep water,” says Rakesh Kumar, who sells small LPG cylinders to the households without proper gas connection. “During monsoon, our homes get flooded and we can’t even walk out,” says Murari Lal Gupta, engrossed in playing cards with Kumar to beat the afternoon lull.

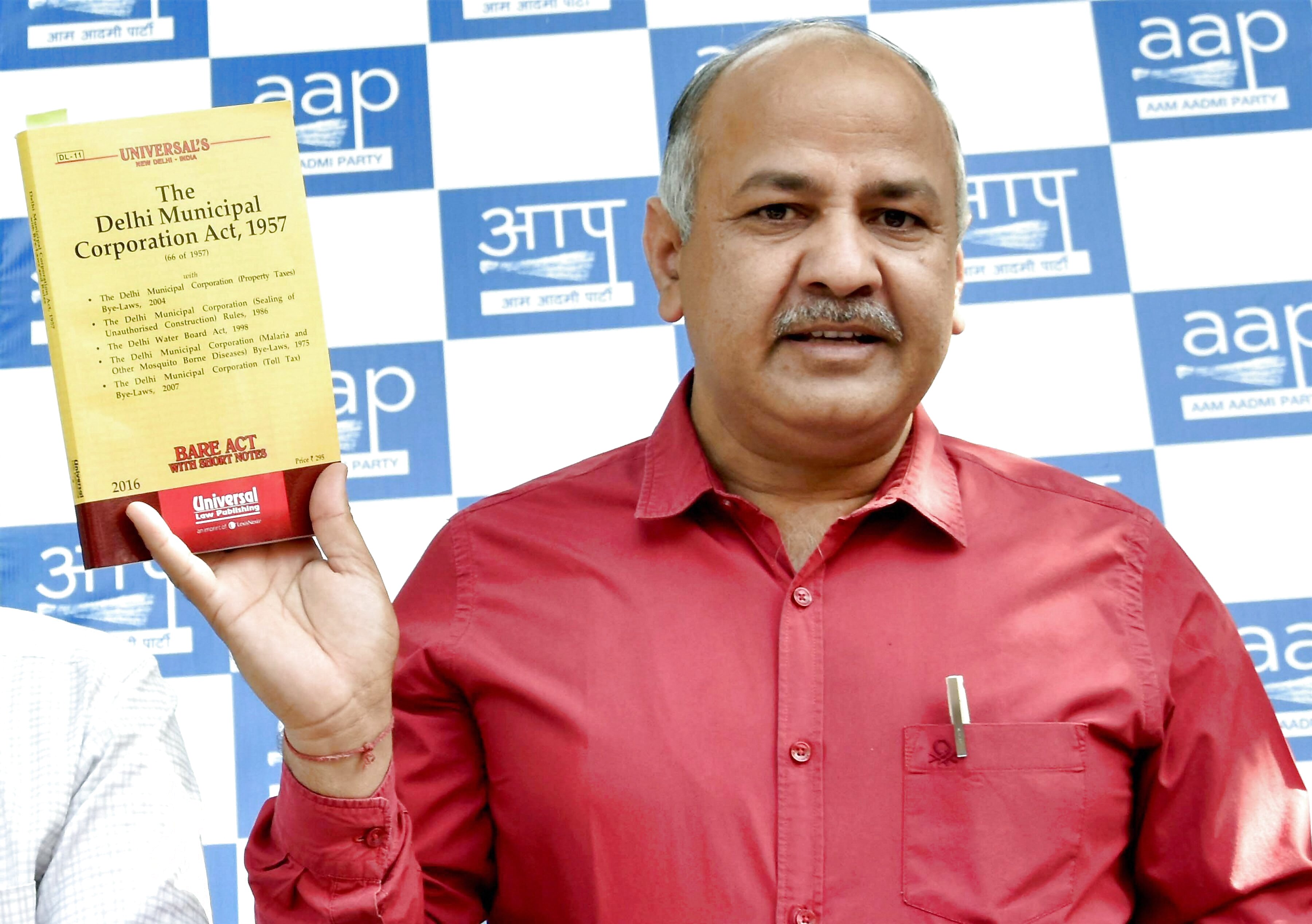

However, sitting ward councillor Neeraj Gupta’s office cites rules which prevent development work in ‘unauthorised’ areas like Sangam Vihar. “Most people who come to us with complaints return angry,” says an aide of the councillor. AAP’s Pankaj Gupta, who is contesting from one of Sangam Vihar’s four wards, is confident that the under-construction sewerage system will win him votes. “We have also provided free drinking water to 70% houses,” he says.

The Delhi government dispensary, nearest medical facility, often tells patients to go to private doctors. “If we had money to go to a private clinic, why would we stand in long queues outside the dispensary?” asks Mamta.

People here have lost faith in government hospitals or dispensaries. Neelam, a housewife, had to spend Rs 12,000 in a private clinic to treat her two children and husband, losing out on year-long savings. Zubeida has a similar story to tell as everyone in her seven-member household fell prey to mosquito-borne diseases.

Over the years, various layers within the underprivileged have emerged. While the residents of older settlements now expect more than just basic amenities, those who have migrated recently are struggling to make ends meet. For example, those benefiting the most from better water and electricity supply in Sangam Vihar are the house owners. Those living on rent in such areas, like fruit seller Umesh Pandey and e-rickshaw driving Mohammed Asim, pay inflated bills. Pandey and his two roommates, also workers, pay an electricity bill of Rs 2,000 a month as the landlord charges them far above the government rates.

Comments

0 comment