views

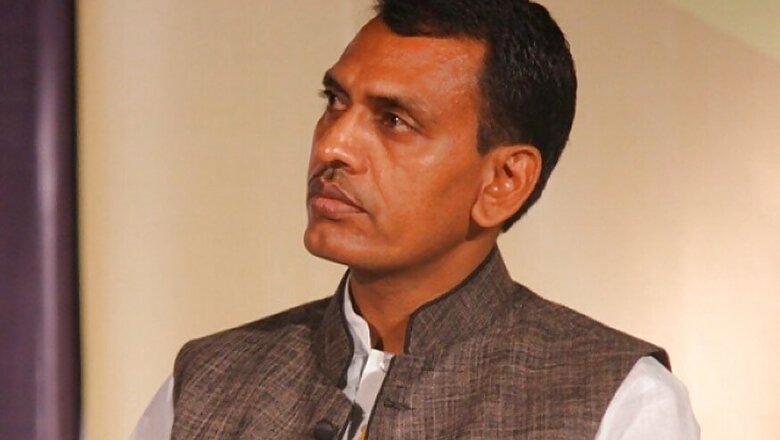

New Delhi: Bhanwar Meghwanshi - a karsevak whose chant of “Ram-ji ke naam par jo mar jayenge, duniya mein naam apna amar kar jayenge,” (Those who will die for Lord Ram will be immortalised) reverberated in the ’90s – is disenchanted at the lack of marginalised voices of Dalits and Adivasis in the national decision making bodies of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS).

He writes about his experiences of being a Dalit karsevak (one who serves a religion for free) and vistarak (householders who can marry and yet continue working in the RSS) in a book titled I could not be Hindu – The story of a Dalit in RSS.

The book was initially junked by some popular Hindi literature publications. However, it was published by Navarud Prakashan in Hindi 2019. The book was later published in English by Navanya.

Meghwanshi, who belongs to Rajasthan’s Bhilwara, was in his teens at the peak of the Ram Mandir movement in the 1990s. Son of a Congress worker, he joined the Ayodhya-bound contingent of karsevaks without his family’s permission.

The former RSS worker in his book writes about experiences that antagonised him from the Sangh. He recounts an especially defining moment in his career with the organisation –food cooked in his house was thrown away by the Sangh contingent that went to the villages of those who died in Ayodhya with their funerary urns.

However, at the time he could not escape the humiliation and had resolved to take revenge.

“I was lower than the shudra, I was an untouchable not one of the four varnas, but an outcast the fifth caste, the avarna. I may well be a swayamsevak but I was not a Hindu all the way. This must be why I was unacceptable. Why I was permitted to rise only up to vistarak, and discouraged from being a pracharak,” he writes.

Struggle to rise in the ranks

Meghwanshi aspired to be a “black cat of Sangh” – no matter how life threw him about, he wanted to land on his feet.

To this end, he poured his heart into activities of the shakha (branch).

He performed havan, granth puja and also served as a chief teacher in the shakha. He would wear the ganvesh (uniform) of the RSS. He also brought out an issue on “Annihilate Pakistan” for Hindu Kesari.

He lost no opportunity to build an image of a Hinduvaadi, a champion of the Hindu cause. “But somehow I felt I was not being accepted the way I wanted to be, as was my right, given all my work,” he writes.

Meghwanshi recalls that sometime after returning from karseva, in May or June of 1990, he expressed to the Jodhpur district pracharak, Shivji Bhaisahab, his desire to become full time pracharak.

Pracharaks, the very spine of the RSS, are “ascetics dedicated to the nation”, who sacrifice their homes and family life.

The response to his request, he writes, jolted him. He was told that although his ideals were high-minded, society would not accept him. “You would have to swallow the insult,” was is superior’s reply.

“My advice is to remain a vistarak for a while and serve the nation in that capacity,” Shivji Bhaisahab told him.

Although at the moment he was convinced that the Sangh would someday succeed in accepting a Dalit pracharak, he was time and again discouraged from aspiring to higher roles within the organisation.

In one chapter of the book, Meghwanshi recalls that he was told, “We don’t really want people like you vicharaks who are constantly questioning and thinking.”

“And thus my thinking made me unfit for the job of propagating the thought of the Sangh.” He told News18.com, “Thinking is discouraged, we are not the mind but the muscle of the Sangh’s activities.”

Earlier in 1988, when he was promoted from chief teacher to karyavah –the highest post in the shakha – there was a dearth of Brahmin swayamsevaks in his village, which he believes could be the reason for his rise.

The structure without the mind of Dalits

In the RSS so far six pracharaks have been the sarsanghchalak (the chief of the organisation), of which five were Brahmins and one Kshatriya.

Meghwanshi observes that questions have been raised about the lack of diversity within the Sangh, but only by those uninformed about it.

“Only a pracharak who has reached the top of the hierarchy would be considered Sarsanghchalak and at the top Dalits, Adivasis and Backward castes are negligible in number. Under the circumstances, there is no chance of any of them becoming Sarsanghchalak for the next fifty years,” he writes.

The author continues to lament the absence of marginalised voices in top decision making bodies like All India Representatives Assembly (Akhil Bharatiya Pratinidhi Sabha) or the All India Working Committee (Akhil Bharatiya Karyankani Mandal).

The karseva saw massive participation by Dalits and Backward Castes, but very few became pracharaks and were restricted to the low levels. The Dalits usually find a place in the Samrasta Manch which is dedicated to societal harmony.

The author remarks that Ramnath Kovind could become the President of India, which is the highest constitutional post in the country, but could never have made the cut to be considered for the unconstitutional RSS.

RSS says equality ‘core issue’

A senior RSS functionary called Meghwanshi's view an individual one and not reflective of Sangh’s approach towards the marginalised Dalits and Adivasis.

He said, “In RSS there is no discrimination on the basis of caste - we don’t inquire about caste. One is promoted on the basis of their work, contribution and intellect. At the state, zonal levels there is fair presence of the Dalits.”

The core issue of the Sangh is to have no discrimination among the swayamsevaks. “This requires change in attitudes for which RSS is working, it is our core issue,” he said.

Comments

0 comment