views

Pacifist Japan is on the cusp of change. Last month, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida unveiled his plan to double defence spending over the next five years, leaving little doubt about the country’s intention to beef up its military capabilities to counter China’s expansionist agenda. The ambitious five-year plan will make Japan the world’s third-biggest military spender after the United States and China. Now, for a country that officially swears by pacifism and which has had no qualms since World War II to be under the American nuclear weapons “umbrella”, besides permitting thousands of US troops to be stationed on Japanese soil, this is nothing short of a revolutionary development.

Things, however, have been changing drastically in the region in the past decade. Since the rise of Xi Jinping as the new ‘emperor’ of China, Beijing has suddenly become an aggressive power, showing no hesitation in taking off the façade of its “peaceful rise” — a ruse used with great aplomb by Deng Xiaoping and his successors to fool the West. Xi, who has modelled himself after Mao, thinks China’s time has arrived. This incidentally has come at a time when the Chinese economy is seen to be faltering a bit. This seems to have pushed Xi to play the nationalism card with great urgency, which may explain China’s growing belligerence on its borders, especially with Taiwan and India. To add to this is the ghost of Ukraine that must be giving the Japanese leadership sleepless nights: What has happened in East Europe can be replicated in East Asia as well. Things have come to such a pass that a senior American military official has predicted that by 2025, the US and China may go to war.

No wonder Japan is today a nation in paranoia. Historically, Japan changes whenever it is deeply threatened. During the 660s, Japan feared the rise of China’s T’ang empire which in alliance with Japan’s old enemy, the Korean kingdom of Silla, destroyed the other two Korean kingdoms of Paekche and Koguryo. “Painfully aware that Japan’s internal disunity made it vulnerable, Emperor Tenmu (of Japan) sought to unify and strengthen the state through the adoption of Chinese central institutional models,” Kenneth Pyle writes in Japan Rising: The Resurgence of Japanese Power and Purpose.

The phenomenon saw a replication in the 19th century when the badly divided Japan faced the much superior West. The result was the Meiji reforms of 1868, which British historian John Keegan described as “one of the most radical changes of national policy recorded in history.” If Japan’s motivation in importing knowledge and institutions to establish a Chinese-style bureaucratic state during the seventh century was fundamentally driven by the Japanese perception of a strategic threat from the Middle Kingdom, the 19th-century Westernisation of Japan was the innate Japanese response to deal with the West.

Japan, an inherently insular and conservative nation, reacts in just the opposite manner when it is under extreme stress. It is this contradiction in Japan’s nature, that made Rutherford Alcock, the first British minister to Japan (1859-64), call the island nation “essentially a country of paradoxes and anomalies, where all — even familiar things — put on new faces and are curiously reversed”. A century later, in 1961, Edwin Reischauer, America’s leading academic expert on Japan who was sent by President John F Kennedy to Tokyo to try to open a strategic dialogue with the Japanese, reached a similar conclusion when he called modern Japanese foreign policy “a subject of bewildering complexity and also vagueness”.

To the Western mind, the Japanese reaction may appear contradictory enough “to fluctuate widely and wildly from isolation to enthusiastic borrowing from foreign cultures”, as Kenneth Pyle writes, or to pursue a phase of rabid militarist expansion, as was the case up to World War II, to be followed by absolute pacifism. Maybe this lack of Western understanding made Henry Kissinger complain too often: “The Japanese do not yet think in strategic terms… They think in commercial terms.” Decades later, Kissinger was forced to change his opinion: “The Japanese system has not been easy for Americans to comprehend. It took me a long time to grasp how decisions are made.”

Mao, in contrast, understood the Japanese better. In one of his encounters with Kissinger, he advised him to shun his condescending attitude towards Japan. “When you pass through Japan, you should perhaps talk a bit more with them. You only talked with them for one day [on your last visit] and that is not good for their face.” Mao had spent several years fighting the Japanese troops, and he was quite clear: That the Japanese should not be slighted; that an insecure and hurt Japan is a dangerous proposition.

Xi may have moulded himself after Mao, but he seems to be lacking the strategic understanding of the Great Helmsman. For, with his aggressive posturing, Xi is doing exactly what Mao had advised Kissinger not to do. The Ukraine war has added to Japan’s anxiety. For, what Russia is today doing in Eastern Europe, Xi Jinping’s China could be doing in Taiwan in near future. The new generation in Japan, especially after Shinzo Abe’s inspired leadership, is desperate to shun the policy of the low political/strategic profile in the international sphere; the latest Chinese challenge, along with growing North Korean belligerence, has only increased the desire for Japan to take a more muscular foreign policy. And, if history is to be believed, when Japan changes, it changes full throttle.

The US, which had always bemoaned the Japanese tendency of single-mindedly pursuing economic growth while leaving their borders for the Americans to defend, must be relieved to see Japan finally waking up to its own security/geostrategic role, especially in the neighbourhood. But the one country that will — and should — celebrate the transformation is India. Faced with Chinese troops on its borders, especially in Ladakh and Arunachal Pradesh, India has been desperately searching for a nation that felt the Chinese threat the same way as it does. Given the geographical advantage, Americans can go on and off on China, but India and Japan don’t have that luxury. They know very well that the Dragon is lurking in the neighbourhood, waiting for an opportune time to hit them hard.

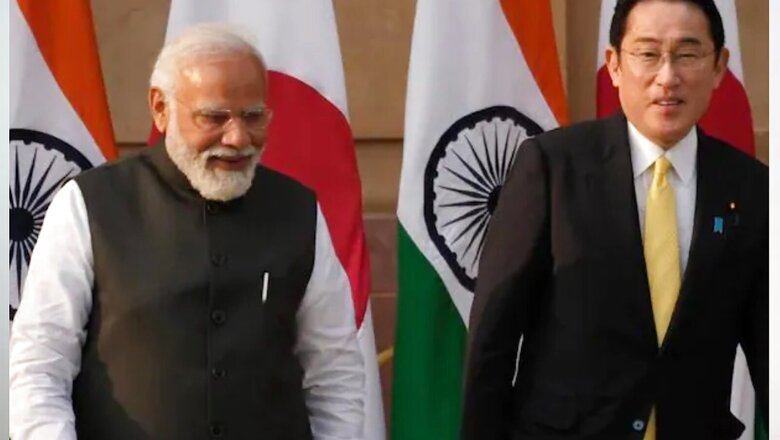

India cannot get a better partner than Japan, especially in dealing with China. What makes the alliance even better is that no other country works so resolutely and with a sense of purpose in the time of duress as Japan does. To add to it, the two countries are currently run by political leaders who understand the importance of close Indo-Japanese ties.

It’s time for India and Japan to tango. If other like-minded nations such as the US, Vietnam and Australia chip in too, this will be the worst-possible scenario for Xi Jinping’s China.

The author is Opinion Editor, Firstpost and News18. He tweets from @Utpal_Kumar1. Views expressed are personal.

Read all the Latest Opinions here

Comments

0 comment