views

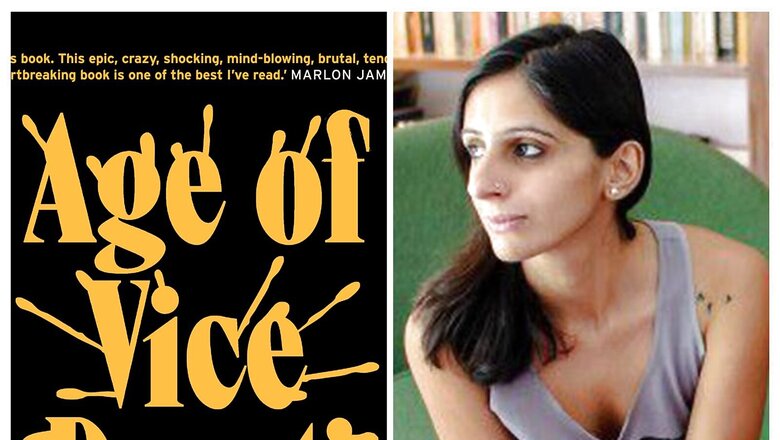

‘Age of Vice- The verdict first

Held: Visual, cinematic, staccato, visceral, crepuscular, unabashedly nonlinear, immersive, mind-blowing, mesmerizing, tender, epic, propulsive, cognitively disruptive, deeply addictive, spellbinder, starkly lyrical, riveting, heart-wrenching, chilling to marrows, thrilling and dazzling unputdownable razor-sharp, sparkling page-turner.

How do I describe the epochal journey of Deepti Kapoor, from ‘A Bad Character’ to her latest sensation ‘Age of Vice’ that has given her the moniker – new Lee Child and new-new Marlon Brando, a new age Mario “Godfather” Puzo and F. Scott “Great Gatsby” Fitzgerald. The answer I get is- let her simply be “Deepti Kapoor, the new genre, archetypal ‘kashér’ whose creations will be read, devoured and acclaimed by generations to come across planet Earth.”

I put the unputdownable tour de force ‘Age of Vice’ as one of the best 20 original novels I have read in 65 years of my young life. And make no mistake, the voracious reader that I am, with all the humility, I say without exaggeration that I have devoured at least 50,000 titles of all genres.

I submit that ‘Age of Vice’ is a true Indian story, real-life non-fiction written as fiction. All a reader needs to do is replace characters in the novel with real living beings. The depiction is so real that I was compelled to read the 548-page sprawling ‘Age of Vice- Kali Yuga’, devouring it in one big gulp, over 24 hours on a trot. And when I thought I was done with it, compulsively, I began again, this time savouring it in slow motion, one chapter and one character at a time, not wanting its magic to wane. And finally, after a week, when it was over, I realized what the true power of the book was.

The moment I finished reading ‘Age of Vice,’ I began my search for its real-life protagonists – Ajay, Sunny, Neda, Bunty, Ram Singh, Dinesh, Vicky and Chaddi Banyan Sunil Rastogi, lurking somewhere in the swanky Delhi colonies or in the rough and tough of Uttar Pradesh, the land from where my ancestors fled during the reign of Lodi Dynasty or notorious Bihar, my native state.

‘Age of Vice’ is so visceral and has made such an addictive, immersive and evocative impact on me, gripping my three-pound southpaw defective brain to such finality that here I am, extolling readers to just grab a copy of the book and get immersed in it. I bet the reader will not be able to put it down till it is over and once it is over, its pages and characters will linger. Make no mistake, ‘Age of Vice- Kaliyug’ has started the year 2023 with a bang, putting the literary world on fire. And as it is part one of the trilogy, wait breathlessly for two more parts to come sooner rather than later.

DECIPHERING THE REAL DEEPTI KAPOOR

A two-line author description at end of the book conceals much and reveals little – “Deepti Kapoor grew up in northern India and worked for several years as a journalist in New Delhi. The author of the novel ‘Bad Character’, she now lives in Portugal with her husband.”

The asymmetry of information about the author led me to the treasure hunt to decipher the real Deepti Kapoor, including my first brief tryst with her in 2015, her varied interviews between 2014 and 2023 after the publication of ‘A Bad Character’ and as ‘Age of Vice’ becomes a global literary rage. I first came face to face with 35-year-old Kapoor, a first-time writer, in 2015 at Jaipur Literature Festival and that brought me to her irresistible debut novel ‘A Bad Character’. Thereafter, I followed her vicariously, reading her blog “I Was a Party Girl, but Yoga Saved Me From Myself”, which she penned on the now-closed HuffPost contributor platform and her two memoirs cum essays “I come from a place on your bucket list” and “Driving in Greater Noida” in Granta Magazine. After that, I have tried to keep pace with her by reading her interviews including her most recent conversations with Parul Sehgal on The New Yorker Radio and with Scott Simon on NPR. The wealth of knowledge I have gathered on Kapoor can make a trilogy, but for brevity, I summarize below what I know of her.

Born in 1980 in Moradabad, 42-year-old Deepti Kapoor spent her early life in Uttar Pradesh, Bahrain, Dehradun, Delhi and Mumbai. She schooled at Welham Girls’ School, Dehradun, and graduated in Journalism with Masters in Social Psychology from Lady Shri Ram College, Delhi. Twin tragedies hit her early in life- the death of her father after prolonged illness and that of her first boyfriend soon thereafter- and left her shattered. She was barely 22 then. As her only brother left for Europe, a distraught Kapoor lived in Delhi with her recently widowed mother and grandmother who was widowed at 25 and recently shifted from UP to be with them. Of her own volition, Kapoor’s way of dealing with grief was to get out of the house and to rebel against the strictures of family life that her mother wanted to impose on her in a strange situation, where three women of three generations jostled with and fought with each other, dealing with their own private griefs and traumas.

Kapoor began her career as a journalist in Delhi where she was witness to all shades of grey for over a decade and later shifted to Goa with her British husband, before migrating to Portugal. In an interview with Elle magazine, Kapoor described her as “volatile, curious, non-judgmental, secretive, stubborn.” She spoke her truth unapologetically – “partied more than worked; a party girl who consumed a lot of drugs, half to escape and half to feel.” But she had to come home every night and her only relief those days was an online job search–in Japan of all places–engaged in the fantasy of a start-again future in an alien land.

Kapoor recalled; the rawness of her grief soon consumed her. “Depression, anxiety, anger, dread” became her strange bedfellows. She had distinct genetic lability with mind maladies, as, in one of her interviews, she described her paternal grandfather as having suffered from either Bipolar Disorder or Schizophrenia. Also, she was candid about her own severe depression and being on Prozac, unsuccessfully seeking redemption through meditation and a horrible encounter with a reputed Delhi shrink. Kapoor re-found her with her immersion in yoga. She admitted, “Yoga eventually saved me from myself (along with the Englishman who became my husband)”.

Kapoor added philosophically – “I suffered trauma, went a little crazy, reached the end of my rope, then met my husband, did escape to yoga, got myself sorted, and began to think of writing.” She further added, “I was not a very good journalist, but good at listening and observing. People I met and the stories I heard went into my novel.” And she also confided, “I lived a lot of what’s in the novel in those years. It’s me but it’s not me.”

Quite a journey her young life has been. And there is something special about her thought process and way of writing. She confessed – “I see the visual situation and infer the interior lives from that. I have an in-built screen in my head.”

Though originally, I sat down to write the book review of ‘Age of Vice’, sooner I realized that, for fuller justice to Kapoor and her creativity, I must begin with ‘A Bad Character’.

A BAD CHARACTER

It was pure play of serendipity when in 2015, ‘A Bad Character’, the debut 200-something page novella by young Deepti Kapoor landed in my lap. As the story is, ever since I started penning my yet-to-be-published memoir ‘Of Madness and Sadness: Life and Times of a Manic-Depressive Indian,’ JLF turned my annual pilgrimage. It was in the eighth edition of JLF (2015) that I was witness to a riveting and out-of-league panel discussion ‘Basic Instinct’ moderated by The New York Times Book Reviews editor Parul Sehgal (panellists- Indo-British Hanif Kureishi, Wales Sarah Waters, American Nicholson Baker and Indian novelist Deepti Kapoor) discussing the taboo subject – ‘Tracing the history of sexual discovery in literature.’

And I was taken in by the boldness of Kapoor talking about ‘A Bad Character’ and the litany of woes she had to overcome writing candidly in India about the trinity of booze, drugs and sex, in an era of fearful culture of censorship.

Once the panel discussion was over, I managed her autographed copy, and before my flight landed in Mumbai from Jaipur, I was so enthralled and captivated that I read it twice. And what struck me was – this story of Beauty and the Beast-type infatuation (I am pretty and he is ugly), thematically tackled raw unadulterated sex, drugs, booze-filled parties and class dissatisfaction. And it was a bare-all narrative about the wretched Delhi conditions from the perspective of a young female protagonist, at a time when sexual violence against women in Delhi was making international headlines with alarming regularity. ‘A Bad Character’ was the boldest and most unconventional piece written by an Indian writer that I have ever read – “else ours is a nation where women and girls not conforming to a particular way of life are unceremoniously dubbed of a bad character.”

Lo and behold, the narrative in this uncharacteristic novel explores the intersection of a young girl in Delhi (India’s prima-donna of vice and sins) and story about unbridled sex, plentiful drugs, and abuse as well as the limits on women’s freedom, quite imaginatively and realistically. ‘A Bad Character’, in part, was an autobiographical sketch. Deepti Kapoor says in an interview about protagonist Idha- “I don’t feel so much distance from her. To a large extent, she is I and I am she.” She further adds – “There was the girl dealing with the death of her boyfriend, which happened to me… the book was my way of exploring grief, desire, trauma, and a girl coming of age in New Delhi.”

The book received mixed reviews, both in India and internationally, and readers’ responses also were rather tepid. Most unforgiving was the response of hypocrite Indians, particularly women. But Kapoor is empathic – “I’d rather fail and write what I want, than write a lie.”

‘A Bad Character’ opens bloodcurdlingly –

“My boyfriend died when I was twenty-one. His body was left lying broken on the highway out of Delhi while the sun rose in the desert to the east. I wasn’t there, I never saw it. But plenty of others saw, in the trucks that passed by without stopping and from the roadside Dhaba where he’d been drinking all night. Then they wrote about him in the paper. Twelve lines buried in middle pages, one line standing out, the last one, in which a cop he’d never met said to the reporter, he was known to us, he was a bad character.”

“These words are his cremation,” says the narrator, about her boyfriend who is dead in the novel’s first line. And the story begins in the retrospect from a time long after his death.

In a fiery, incandescent, dark and hypnotic story, a young protagonist whose actual name is never revealed (though at the beginning, she gives her a name – ‘Idha – lunar, serpentine, desirous’), is “20 and untouched.” Her mother dies when Idha is 17 and her father dispatches her to Delhi, to be raised by an aunt. Living with her in a modest Delhi apartment, Idha feels cramped by boring university classes and by her aunt’s ceaseless attempts to propel her to an arranged marriage. She laments – “I don’t know why it happens. I can’t explain why I’ve been abandoned this way.”

From the very first line ‘A Bad Character’ is a story of Idha’s rebellious love that both shatters and transforms her. “He is few years older, just returned from New York – a rich, rebellious, darker skinned, flawed young man from different social strata.” Idha finds him “ugly with dark skin, with short wiry hair, with a large flat nose and eyes bursting either side like flares, with big ears and a fleshy mouth that holds many teeth”, a wild animal dressed in human clothes, yet she realizes there’s something of the animal in him.”

He is a hideous but irresistible drug dealer. They meet in a cafe one afternoon, she–lonely, hungry for experience, yearning to break free of tradition–casts aside fears throwing her headlong into a torrid love affair, one that takes her where she has never been before. Starting as Idha’s Delhi tour guide, the nameless lover soon turns guide of her sexual desires, opening door to the new pleasurable experiences and closing the door forever on her previous way of abandoned insecure life. Idha narrates- “He held me in his arms afterwards, held me round my waist, pressed his teeth to the back of my neck, whispered in my ear, and he asked me what it was I wanted from the world, what it was I feared. I said I feared everything, and I only wanted to be free.”

In haunting paragraphs, Idha narrates stories of booze, sex, and discovery of a gritty, thrilling India that she never knew existed. The tension that their rocking affair will get exposed becomes unbearable and Kapoor takes the story in darker tragic directions. As the novel becomes more about the young woman wrestling with the effects of her torrid affair, the prose turns more engrossed and elliptical.

Three paragraphs of the book are itched in my memory, first is a powerful sentence- “Him and me, (long dead), sitting in the cafe in Khan Market the day we met.”

And second, depicts, sad but true specter of Delhi as Idha says-“I want just to put my music on and go out there, make my lungs burst, and run. Only Delhi is no place for a woman in the dark unless she has a man and a car or a car and a gun.”

And lastly the prophetic paragraph-

“It’s in this desperate life of preservation that death is held. Holding on to life only to die unblemished, to make it to the end, untouched by sin. And for what? What then? The girl sees this, and yet there’s nothing to be done, nowhere to go. Nothing for her to do but grit her teeth, calm voices inside.”

The New York Times found ‘A Bad Character’ “intoxicating, that tackled a more universal theme of female desire — inclusive of but not restricted to erotic; here was the story of a young woman’s hunger to be free. But for any woman to possess and understand herself in a conservative society, expectations and traditions must die. Fittingly, bodies are set aflame.”

The Publisher’s Weekly found the story and the style of Kapoor reminiscent of Marguerite Durras’s ‘The Lover’ but added – “When fused with the vivid Delhi scenes, Kapoor’s novel ventures into exciting and original territory.”

‘A Bad Character’ alternates telling story in first and third person, and in past and present tense; is unafraid and raw, lyrical in parts, riveting, gritty, mournful and frank, a narrative in minimalist, unsentimental style that grows on reader’s mind like old wine and which compels repeat readings, introspections and reflections.

‘A Bad Character’ heralded the arrival of a fabulously uncommonly, gifted new Indian writer. Except that few Indians noticed her. And fewer read it. A large gestalt of Indian women disapproved, despised and frowned upon bold Idha, her taking to drugs and her incorrect nonconformist behavior which militated against the idea of a proper Indian woman and how she must eschew sex that was bad, and oozing raw sexuality that was taboo.

The bold depiction in ‘A Bad Character’ transported me to another era, to my young college hostel days where three forbidden must read erotic pieces circulated freely and were read universally in both boys and girls hostels – ‘Venus in India’ (published in 1889 by Captain Charles Devereaux, a pseudonym), purportedly autobiography of a British Army Captain and his erotic adventures with three young daughters of a British colonel; ‘Lolita’ (1955, by Vladimir Nabokov) and Secret Garden: Women’s Sexual Fantasies (published 1973, Nancy Friday).

‘A Bad Character,’ which boldly brings in open the sexual initiation of a 20-year young Indian woman who burns with a longing, was, is and will be an original liberating literary piece that shatters the Indian glass ceiling.

AGE OF VICE- KALI YUGA

‘A Bad Character’ marked the arrival of Deepti Kapoor, but it did not make her rich or famous. In 2015, she wanted to finish another novella quickly and start the third, same year. It did not happen. And it was nine long years before her second, the sprawling 548-page ‘Age of Vice’ hit the road. In Kapoor’s own words, when she set out to write ‘Age of Vice’, she had very limited success as a writer and was reaching a point where she had to decide whether to keep going or find a steady job. ‘Age of Vice’ to her felt like ‘one last shot.’

Then something astounding happened. Something changed. It happened well before the release of ‘Age of Vice’ on January 3, 2023. Its manuscript sold publishing rights in 20 territories and sparked 20-way bidding war for TV and film rights, won by FX and Fox 21. In Bollywood, directors like Zoya Akhtar and Anurag Kashyap wanted the movie rights.

What makes ‘Age of Vice’ a compelling unputdownable read?

- It is visceral with ferocious plot, arresting characters and electric dialogue with a thrilling style and extraordinarily rare literary piece of the art.

- Kapoor’s authenticity in bringing out the truth of real political and moral compass of 20th century and early 21st century India and its naked horrific collision between the two worlds of dissolute wealth and harsh poverty.

- A stunningly new genre of writing. And pure cinematic entertainment-—a juicy story of power, corruption, pleasure, sex and drugs, love and loyalty, respect and violence and everything a real pot boiler is made of.

This is just the tantalizing beginning. There is a lot more. More about it a bit later.

But what ‘Age of Vice’ is all about? It is rightly compared to The Godfather and The Great Gatsby. But it is much more. It is a page-turner, fuelled by seductive wealth, chilling corruption, and unfathomable destitution. It is about power and abuse of power. It deals with politics and patronage in a manner and at a level rarely dealt in Indian literature. It is about complicity. Corruption, its causes, consequence. Crony capitalism. Richest of rich. Poorest of the poor. It intersects extreme wealth, powered with extreme inequality, penury and suffering. It is about nonbeing of have nots. It’s about emerging new India post 1990s liberalization and globalization. It is about the struggle between entrenched and aspirational classes. Propulsive thriller it is, but it is also real-life saga of dabbling in contemporary Indian sociology, psychology, economics and politics in all complexity and nakedness.

And it is a lot more.

It conjures real-life saga, which we read in newspaper headlines, told as a captivating literary gem. It is about Delhi, the microcosm of India- a metropolis that is both beautiful but horribly violent and unjust. ‘Age of Vice’ has received new-fangled unparalleled international attention and accolades, unnaturally unusual for a book, by not so well-known novelist from this part of world.

It is time to deep dive. And I begin, where ‘Age of Vice’ ends- “Past one a.m. somewhere in Punjab, the HRTC bus to Manali pulls over at the dhaba on the side of the road. The passengers file out sheepishly. Ajay among them in his black T-shirt, his black pants. His Lugar has already been thrown. In this world all that belongs to him is a few thousand rupees and his grief and freedom. He’ll vanish into the mountains of his youth.”

Now fast forward to where it all began-

“Five pavement dwellers lie dead at the side of Delhi’s Inner Ring Road. It sounds like start of a sick joke. If it is, no one told them. They die where they slept. Almost. Their bodies have dragged ten meters by the speeding Mercedes that jumped the curb and cut them down. It is February 2004. Three a.m. Six degrees.…. And one of the dead, Ragini was eighteen-year-old. She was five months pregnant at the time. Her husband Rajesh twenty-three, sleeping by her side was also dead…A cruel twist of fate: this couple arrived in Delhi only yesterday.”

And here comes the twist.

It’s Mercedes, a rich man’s car, but when dust settles and police-posse arrives, there is no rich man, behind the wheel is a shell-shocked drunk to the hilt servant, unable to explain strange series of events that led to the crime. Nor can he foresee the dark drama that is about to unfold. 22-year-old chauffeur Ajay “Mercedes Killer” remains taciturn in police lock up despite torture and in jail, even when attacked by three goons with razor blades. Then suddenly, Ajay’s wakes up, mercilessly attacking his attackers in jail and stands mortally fearful in prison hall, reeking in blood.

And the story takes a dramatic turn in jail warden’s office, where Ajay as conversation unfolds-

“The warden asks him to sit.

“Have a cigarette. Help yourself. There has been a mistake.,” he says. “If I had been told. This would never have happened.” […] “You should have said something. You should have made it clear. You should have let us know. Why didn’t you let us know?”

Ajay stares at the food, at the cigarette pack.

Know what?”

The warden smiles. “That you’re a Wadia man.”

And the cat is out of the bag– Mercedes killer is no ordinary mortal, no ordinary chauffeur. He is not a nobody. He is Wadia man. And Wadia family symbolizes seductive wealth, startling corruption and bloodthirsty violence—”loved by some, loathed by others, feared by all.”

After the deadly accident and introduction of Ajay, the reader is initiated to India’s most corrupted, politicised, powerful underworld family— and from there begins a journey one is forced to traverse without pause to take a breath. And hereinafter begins the epic saga written with lots of empathy, trepidation, and research, less of a fiction and more, the truth of “A Wonder that is India.”

Set in Delhi and UP, alternating between 1991 and 2008, the opening sequence of ‘Age of Vice’ sets the tone for the great saga, contending with the rise of mafia raj, human trafficking, catastrophic urban development, extremely disadvantaged have nots, plentiful violence, and obscene conspicuous consumption of gangsters turned industrialists turned politicians and political ring masters.

And importantly, a lot of fiction in the novel is non-fiction, reality personified based on true stories and true characters, about whom Kapoor took meticulous notes during her decade long tryst with journalism in Delhi. True happenings captured as she saw, heard and read with amazing dexterity and candour. People she had known or met – miraculously, she captured these true narratives in inebriated state, as she confesses elsewhere “stoned or drunk.”

‘Age of Vice’ revolves around four central characters – Delhi, Ajay, Neda, and Sunny, three lives dangerously intertwined. As the plot thickens, subplots emerge with stories within the story and novellas under the novel. How else one explains ingenuity of Kapoor, who keeps readers captivated introducing new characters, every now and then, with last such narrator appearing on page 442 as a 34-page long detour unheard of in a literary creation. The pace of the novel is such that it summersaults readers faster than a superhero movie.

DELHI

Like her first novel ‘A Bad Character’, Delhi is the central theme of ‘Age of Vice’ except that narrative here is more brutal. The most beautiful Delhi, the most horrific Delhi. The seat of power, abode of rich and famous, a city of lavish estates, farmhouses, extravagant parties, overflowing booze and drugs, predatory business deals, and cold blooded calculated political influence. Delhi – a city of gross injustice and inequality. Of pervasive oppression. Where being poor is ugly- branded encroachers and thieves. A city of sin.

Delhi, a city I love. A metropolis I hate.

AJAY

Ajay, the humble heart of the novel, is also its most vulnerable—a Dalit boy whose life gets ruined when he is eight years old, over a fight over a wandering goat that destroys his family- father killed, sister raped and sold to brothel, Ajay himself sold by mother as barter for family debt. ‘Age of Vice’ begins and ends with Ajay, with Kapoor largely spending first 170 pages weaving Ajay’s story, who lands as indentured labour in mountains of Manali. When his master dies, Ajay, aged 16 or 17, gets to work in a cafe in the mountains where he meets Sunny, the only son and heir to a big criminal business fortune in New Delhi. It is through Ajay that readers get the first glimpse of Sunny. And then, Ajay lands in Delhi where he rebuilds life through hard work and constant servitude. But new life as Sunny’s man Friday, eventually turns his nemesis. Life of Ajay is to serve, and the story never lets its reader forget it. About Ajay and his servitude, Kapoor writes, “He has become a name,” …. To be called and used. Turned on like a tap.”

Invisible Ajay is devoted to service and makes sure that every wish is fulfilled even before you know that you have that need. And Ajay is not a fully fictitious character but is inspired by a similar indentured young boy from Bihar whom Kapoor once met in a guest house in similar circumstances in Himalayas, an experience to which she juxtaposed stories of her similar invisible silent workers, always willing, attentive, and ready to serve in private mansions of her rich, famous and infamous friends where she frequented in her twenties.

Readers and reviewers in America and Europe see Ajay as pivot of the novel, unlike Kapoor, for whom Ajay’s story is a big starting point but a launch pad from where she transports readers fast to the world she wants to portray-the world of Delhi, with Sunny and his family, stories of corruption, violence, landgrabs, slum demolition and crime.

NEDA

After 170 pages on Ajay, Kapoor spends next 200 pages with Neda, a young, curious journalist caught between morality and desire, who aspires to be something, though not sure what. Neda is a pedigreed girl with cultured, scholarly, and radical parents from genre of educated families that grew in prominence in colonial era. Homed in Malcha Marg, Neda’s cash-poor, prestige-rich inheritance carries an aura that nouveau-riche families like Sunny’s take many successful generations to acquire. Neda willingly gets entrapped in Sunny’s lust, disruptive glamour, dangerous life, heady booze, and sex, swept in secret trysts in luxurious hotels and elaborate dinners. But by the time she discovers that the relationship is jinxed, she is already out of her depth, in deep trouble, too late. At one point, Neda confesses “going for a meal with Sunny was not about the food. […] It was the performance; …waiting to see what would happen next […] in this world they had conjured.”

Finally, the desolate and emaciated Neda, whose baby, Sunny’s child was killed in embryo, trapped in a London apartment, ejected there by Sunny’s gangster father, writes in a mail to her editor (a mail she never sends)- “Nothing will change. This is Kali Yuga, the losing age, the age of vice. People on the road will remain dead. The baby will still be born. The Gautam’s of the world will thrive. Ajay’s of the world will always take the fall. And Sunny? I do not know anything anymore. The wheel will keep turning towards the dissolution that will swallow us all.”

Abovementioned sums the travesty of total disruption of Neda’s life caused owing to her dalliance with Sunny. Like Ajay, Neda is not imaginary. Deepti Kapoor confesses that a part of Neda is Deepti, in her 20s, one who partied a lot, often recklessly.

SUNNY

The first section of the book is Ajay’s story and the second gives Neda’s perspective. But the last part is about Sunny, a tragic figure, part soul destroying part mesmerizing, heir to massive fortune of his gangster father but not as ruthless. Sunny is a heartbreaker who believes he has a role to play in the struggle between Delhi’s entrenched and aspirational classes. He has romanticized vision to transform Yamuna riverfront ala London on Thames to beautify Delhi.

A weak character, Sunny has impossible choices: to go his father’s way of ruthlessness, unchecked power, and unstoppable wealth or to carve his dreams with Neda. And he makes his coward choice in the night of Mercedes’s accident- returns to his father to please him, saving Gautam to use as a pawn to enhance father’s empire, sacrificing Neda and loyal Ajay. Sunny, who did not want to be gangster’s son anymore and who once said, “I love beauty. I want to create beautiful things. But that is the last thing they understand. They want me to have a beautiful surface and be rotten to the core, like they are” proves his own unfortunate predicament right- “No one gets their life back. No one ever gets it back. Life just runs away from you. It never comes back, however hard you try, however much you want it to. This is the lesson you should know. You have to adapt or die.”

BUNTY WADIA GANG

And then there are support cast, starting with all powerful, ruthless, low profile gangster kingmaker Bunty, Sunny’s father, with naked but covert lust for power and pie in everywhere–landgrabs, liquor, transport, controlling UP politics and police through his stooge Ram Singh, the CM. Ram has a son Dinesh, who wants to break away and do good like Sunny, but is more resolute and purposeful; there is Bunty’s brother Vicky, a criminal with his own nefarious ambitions. As the epic draws to close, there is climax- Sunny’s marriage of convenience that add Punjab to Wadia’s territory. Marriage guest list is “mighty and powerful” of India. And there is a Chaddi Banyan gang killer on prowl for his prey.

And the tension builds up to an end that readers must decipher themselves.

All I can say is there is more to the epic saga, hold your breath, read part one and await part two and three of this untold saga of corruption, collusion, crime, inequality, and violence, where possibly one will see more of Sunny and Dinesh, Neda and Ajay, and Vicky, the great.

POSTSCRIPT

A native of notorious Bihar, I have had tryst with Bahubali politicians. I have worked in difficult areas of Uttar Pradesh and Delhi for a decade and half. During the relevant period, I have been strategic consultant to Greater Noida authority. I have also passionately done night outs on the streets of Delhi, including Yamuna Pusta area, trying to understand the travails of homeless and slum dwellers. I have been witnessing to the naked dance of Delhi land grab. And last but not the least, like innocent Ajay who landed in Tihar Jail, without committing any crime, I have spent quite a few days in notorious Patna Central Jail as under trial without committing any crime. I can palpably feel the true real-life characters of ‘Age of Vice.’ They are there, not gone anywhere, waiting for their next prey.

Akhileshwar Sahay is a Multidisciplinary Thought Leader and India based International Impact Consultant. He reviews books for News18 Platform. Views are personal.

Read all the Latest Opinions here

Comments

0 comment