views

Since the worrying alerts were issued by global regulators signalling the problems with Made in India medicines, the country’s health ministry swiftly sprung into comprehensive action.

It initiated an extensive campaign to rectify the chaos and weed out the culprits. Objectives of the drive were too many — from protecting the image of India as a “pharmacy to the world” to earning back the trust of global regulators and continuing healthy exports.

The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare shortlisted 209 ‘risky manufacturing sites’ to conduct inspections in three phases, starting in December.

The objective of India’s massive drive was to unearth the problems in drug making. So far, around 162 firms have been inspected. The investigation reports disclose several serious lapses including selling drugs without bills, buying raw materials without invoices, quality compliance issues and manufacturing fake medicines.

A few investigation reports by CNN News18 here and here and here.

How India conducted the massive drive?

Six teams were initially formed to conduct the audits and raids at identified drug manufacturing units along with the state drugs control administration.

A committee of two joint drug controllers was constituted at the apex drug regulation body, Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation (CDSCO), to monitor the process of inspection, reporting, and subsequent action.

The entire move was driven and monitored by Union health minister Mansukh Mandaviya.

Results of the drive

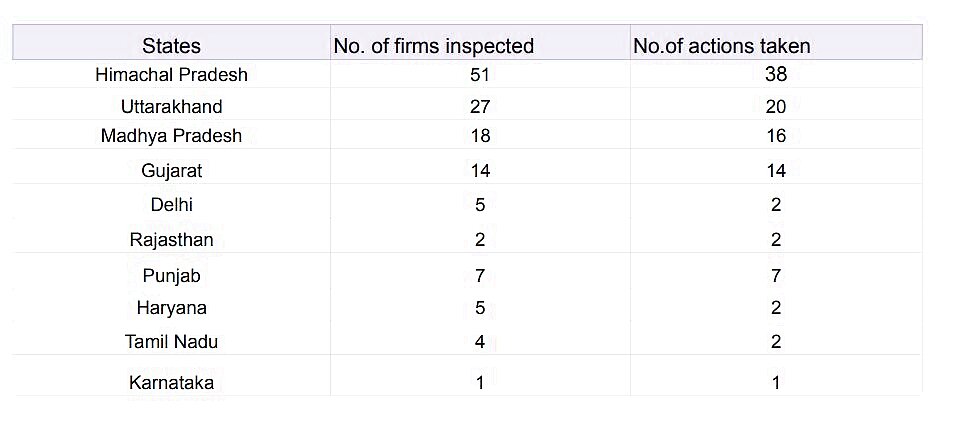

Data till August 2 shows that the ministry has inspected 162 firms out of which 143 have faced actions.

The government data shows 40 stop production, 66 cancellation or suspension of product or category licenses have been issued. Around 21 warning letters have been handed over whereas 143 firms have been given show-cause notices.

In Himachal Pradesh, 51 firms have been inspected followed by Uttarakhand (27), Madhya Pradesh (18), Gujarat (14), Delhi (5), Punjab (7), Haryana (5) and more.

After conducting the massive drive, which is still ongoing, the government announced its decision to implement Schedule M.

Schedule M is the local version of WHO-GMP – the basic minimum requirement for drugmakers – which will now be implemented on around 8,500 pharma units.

According to government data, there are around 10,500 manufacturing units in the country, of which at least 8,500 are in the category of micro, small and medium enterprises (MSME). Of these, 2,000 are approved by the World Health Organization and certified as WHO-GMP (Good Manufacturing Practices).

Are we done?

While the latest bold moves by the government are welcoming, India is just getting started.

Experts told me that checking the compliance of Schedule M will remain the most difficult task in the coming months.

Three experts, who requested to remain anonymous and work in regulatory compliance, consultancy and is an industry veteran, feel that it’s almost impossible for the government to check the compliance of Schedule M.

In fact, India, at present, does not have enough resources in terms of the number of inspectors and then trained inspectors to audit the facilities claiming to be Schedule M or WHO-GMP compliant.

Sample this: Till June, Maharashtra FDA was suffering from a massive shortage of inspectors as 59% of the 200 sanctioned posts were lying vacant.

They recently made an amendment for hiring drug inspectors by removing the eligibility criteria of three years of experience. Now, they only need a pharmacy degree.

Kerala also reported a severe shortage where more than 30,000 medical stores were inspected by just 47 drug officers. Similarly, several other states have reported shortages in the last two years.

“Right now, it’s difficult to inspect 2,000 manufacturing units and we are talking about checking 10,500 units – this sounds more hype than reality,” an officer who works with a consultancy associated with the central government for giving advice on health matters told me.

“It took several months to conduct risk-based inspections at just 160 odd firms and we are aiming to check the compliance at 10,000 firms in the next six months to one year,” the officer further said.

In addition to addressing the scarcity and skills gap, the health ministry must also provide clear guidance on implementation, especially given the complex nature of health issues, which also fall under the jurisdiction of the states. Hence, “Who will be the enforcement body?” needs to be answered clearly.

Also, the move must not become a harassing mechanism for those who are willing to change.

China case study

China had massively upgraded its pharma manufacturing practices which involved the display of solid political willpower as well as the commitment of the health regulators.

In 2017, China’s drug regulatory authority joined the ICH (International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use). Since then, China’s drug registration administration system had accelerated its integration with international practices.

By joining ICH, the country needs to adopt global standards for drug manufacturing and upgrade its entire industry. To achieve that, China went on to shut down several pharma firms that failed to comply with the given rules and regulations within the stipulated deadline.

Back in February 2020, VG Somani, the former Drug Controller General of India, announced the intention to soon become a part of ICH. However, this aspiration has remained a remote goal, growing even more distant over the past year. (Starting October 2022, India faced increasing drug alerts and complaints from global regulators including Gambia, Uzbekistan, US FDA, WHO and others.)

Since 2018, India has also been planning to join Pharmaceutical Inspection Co-operation Scheme (PIC/S) which aims to provide good quality medicines to the public by harmonising Good Manufacturing Practices (GMPs) among countries.

It is joined by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and several other drug regulatory bodies across the globe. However, this also remains pending.

Joining these conventions or schemes allows access to Indian medical products in many more countries apart from enhancing the trust factor and reputation in the global arena.

The ministry, in collaboration with the Department of Biotechnology, has sought expert guidance from multiple consulting firms on joining these groups. Nonetheless, they have yet to take action, likely attributed to the factors that began emerging a few months ago, shedding light on the quality crisis.

In short, the willingness to acknowledge the disorder in the industry and the commitment to eradicate chaos, along with the firm statements made by Mandaviya to the industry, should not be in vain.

It’s essential to understand that the adoption of Schedule M is merely the initial phase, a fundamental one at that. India must ensure strict adherence throughout its manufacturing units, and this enforcement must be conducted with utmost thoroughness.

The rules are simple: enhance capabilities, enforce regulations, close down those unwilling to adapt, but spare companies from unnecessary badgering.

Comments

0 comment