views

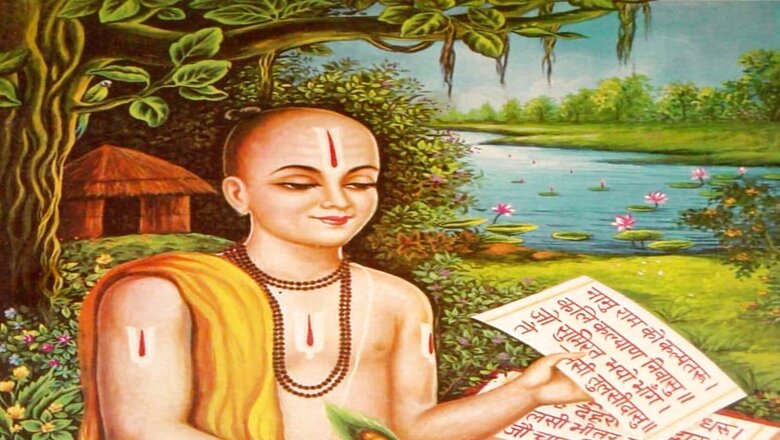

Courtesy Swami Prasad Maurya, Ramcharitmanas, or the Awadhi Ramayana, is again in the news four centuries after Goswami Tulsidas composed it. To Tulsidas, a Sanskrit-knowing Brahmin, the composition was a liberating experience, a coup against his own class. By giving Ramayana to the masses, in their own tongue, he was acting as a farsighted progressive writer. In the ensuing centuries, his Ramcharitmanas infiltrated every Hindu home in Northern India and enjoyed a popularity that Valmiki Ramayana never attained due to linguistic barriers. He also instituted Ram-Leela, the enactment of the life of Lord Rama, every autumnal Navaratri. Its popularity could be gauged from the fact that thousands of Ramlila Maidan in villages, townships and cities of India are named in honour of this annual event. Tulsidas was the first ‘de-coloniser’ of Indian minds, in whose writing, iconoclastic influences of Islam were thoroughly absent.

Way back then, the Ramcharitmanas project faced the ire of the orthodox Brahmin community, who perceived this rendering of sacred Ramayana into non-Sanskrit language as a sacrilege. However, in the 16th century, the dominance of Sanskrit was already crumbling, a process started by Sant Dnyaneshwari in the 13th century in Maharashtra, when he wrote Jnaneswari Gita and Amritanubhav in Marathi instead of Sanskrit. Tulsidas advanced the historical process. He luckily found support for his vernacular language project from Madhusudan Saraswati, a highly revered monk of Varanasi, who is considered one of the four pillars of Advaita Vedanta in India (the other three being Adi Shankaracharya, Vidyaranya Swami and Swami Vivekananda). Madhusudan Saraswati was the last important scholar of India, who found enduring fame by writing solely in Sanskrit. He was originally from eastern Bengal. Since Ramayana had already been rewritten in Bengali a century earlier (by Krittibas Ojha), Madhusudan Saraswati had little hesitation in approving the idea of Ramayana in Awadhi. He described Tulisdas, a fellow Varanasite, as a shrub of holy basil (Tulsi in Sanskrit) in the garden of Varanasi, whose blossom/poetry collection (the word Manjari could interchangeably mean both in Sanskrit) was kissed by a bumble-bee called Rama (Rama is dark as bumble-bee according to Ramayana). The Gita Press version of Ramcharitmanas acknowledges this indebtedness to Madhusudan Saraswati in welcoming Tulsi’s composition.

With changing times, Tulsidas’ critics have changed. The Brahmins, very few of whom actually know Sanskrit, would prefer Ramcharitmanas. There is no reason–in reality–to dislike that great saint in any other section of society. Tulsidas played a great moral and intellectual role in keeping the Hindu society rooted to its ethos when the sword of Islam was staffing through the sub-continent. He felt the Hindu society should stand up valiantly for its culture. His Doha (couplet) written during the pilgrimage to Vrindavana at the sight of deity is highly symbolic– Kaha Kahon chhabi aaj ki bhale bane ho nath/Tulsi mastak tab nabai, jab dhanush vaan lo haath (What to say, you look amazing in today’s attire/Tulsi’s head, however, will bow when you raise bow and arrow). It was not an effusion of sectarian attitude, but an appeal for armed defence of the Hindu society. This was indeed the time when sects of monks had started bearing arms, as amongst the Sikhs, to defend against Islamist attacks on them. The legend has it that the deity in Vrindavana temple temporarily transformed from Lord Krishna to Lord Rama at Tulsidas’ supplication. In place of the flute, the deity was bearing a bow, arrows and quiver.

It was exactly this virtue that Tulsidas was pointing towards in the much-maligned chaupai in the Sundara Kand in Ramcharitmanas. Lord Rama, who was previously waiting for the Ocean to give way so that his army might crossover to Lanka, was moved to anger before threatening to dry up the huge blue water body. Without fear there is no affection, he says. At this, the deity of Ocean falls at his feet and says he was only acting according to the laws of nature set by the Divine himself. It is in this context, the deity of Ocean utters, dhola gavara sudra pasu nari, sakala taRana ke adhikari. The English translation of Ramcharitmanas (1968), published by the Gita Press, Gorakhpur says- “A drum, a rustic, a Sudra, and a beast, and a woman- all these deserve instruction.” Here, taRana clearly means (in Awadhi) guidance and not physical abuse. These, however, are words of the deity of Ocean, not Lord Rama. The Ocean justifies its position by saying that the Divine (Lord Rama) can change the rules of nature set by the Divine himself, by instructing the Ocean, but it would bring no glory to the Ocean to act against natural law (by allowing path). On this, Lord Rama asks for a way out. The deity of Ocean informs that two commanders in his Vanar Sena, namely Nil and Nala, got a boon in their childhood, that stones touched by them could float in the water. The two brothers could construct a bridge leading to Lanka. This was how, according to Ramayana, the Ram Setu was built that was used by Lord Rama’s army to march to Lanka.

Ramcharitmanas has many dramatic moments and this was one of them. Can one censor the dialogues, in a drama or film, ascribed to the villain or adversary? Can one say, as Manoj Raghuvansi asked Udit Raj, in a television debate in 2006 to remove the line of Gabbar Singh from the script of Sholay? Incidentally, I was the other panellist in that debate, in a now-extinct television channel. The debate was sparked by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) overture towards the Dalits, which Udit Raj tried to dismiss and the RSS representative could not join the debate due to personal issues at home. It is a pity if, over the last 15 years, the Dalit political leaders’ knowledge of Ramcharitmanas is limited to this one line.

The Ramcharitmanas was one of the finest products of medieval Indian literature. At the same time, it might reflect some prejudices of the era in choosing the allegories. In those days, there was no book review on the pages of leading national dailies or book reading sessions in India International Centre. Had it been so, Goswami Tulsidas might have been more circumspect even about the words put into the mouths of Rakshasas.

Here, however, it is not the literary aspect of the Ramcharitmanas that is under fire. The political critics of Tulsidas wish to project him as a representative of the Brahmin community, prejudiced against the Dalits. The contemporaneous Brahmin society of Tulsidas would have been astonished. They saw him as a rebel against his own class, who made the sacred Ramayana a property of the unwashed masses.

We must honestly ask ourselves- does burning books, from Manusmriti to Ramcharitmanas, actually helped the Dalits? It is blind rage, the kind which drove Rohith Vemula to commit suicide in 2016. It is easy to destroy things in a feat of rage, which might provide an outlet for the anger of some. However, will it help the Dalits to re-imagine their past or re-engineer their future? While Jihad might be equally frenzied, they are at least backed by a solid history of establishing Islamic rule in large parts of Asia and Africa and the Balkans. What, however, are Dalits trying to achieve by revisiting the past? They need political emancipation, social mobility, educational opportunity and economic freedom. Above all, they need a life of dignity and acceptance across society. Could this be achieved by burning books, when they would actually prosper by reading more books? Like in the parable of Ramcharitmanas, where Lord Rama ends the confrontationist attitude with the Ocean, yet finds out a way to achieve his purpose intelligently and amicably, the way forward lies in cooperation, not confrontation.

Article 17 of the Indian Constitution abolishing untouchability is comparable to the US decree (1861) abolishing slavery. While in the US, the northerners showed the courage to end the degrading socio-economic evil, the Confederate states turned against them, triggering the American Civil War (1861-1865), which caused more casualties than American fatalities from the War of Independence to Gulf War (1991) combined. However, in India, no section of the society turned against the Constituent Assembly, but rather welcomed this humanistic decision. The Dalit leaders should provide a constructive agenda before their supporters. They would not be lacking in support from the rest of the Hindu society.

The writer is the author of the book “The Microphone Men: How Orators Created a Modern India” (2019) and an independent researcher based in New Delhi. Views expressed are personal.

Read all the Latest Opinions here

Comments

0 comment