views

Not far away in the midst of the colonial style colonnaded arcade of Connaught Place, the shopping centre, perched on an empty plot, was the rather untidy, makeshift temporary structure of India Coffee House where Hindi writers and several artists met on an almost daily basis. This was adda baazi, Delhi style.

The National School of Drama worked out of a really small space. Within this my father (Ebrahim Alkazi) carved out an excellent studio theatre by removing a wall between two rooms to make an eighty-seat auditorium and a stage as large as the seating. Many ‘huge’ productions of classics, Sophocles’ Oedipus and Shakespeare’s King Lear were presented here in Urdu, while later Mohan Rakesh’s Lehron ke Raj Hans, among others, got its first production.

In 1967, my father created an outdoor performance space behind Rabindra Bhavan, built by the students themselves. As noted director M.K. Raina recalls, ‘NSD had a meagre budget those days. We worked three hours a day building this theatre and Mr Alkazi carried bricks along with us.’ He named it the Meghdoot Theatre once again.

The huge peepul tree that formed the backdrop to the acting area lent a real gravitas to any production mounted before it. For different plays, different habitats were constructed. Godan by Premchand in a stage adaptation titled Hori saw a field of corn and a couple of village huts typical of eastern UP, for Tughlaq elegant arches framed the space while Yerma was played against the textured white walls of a Spanish village. Years later, long after my father had left the National School of Drama, I had an opportunity to direct The Jungle Book in this magnificent open-air setting with the tree as a central character.

Creating something out of nothing at all—a Mumbai terrace transformed into an open-air theatre, a peepul tree defining a stage, a curtain of hessian splattered with Plaster of Paris to create a setting, requires real imagination. My father excelled at this and also worked at next to no cost.

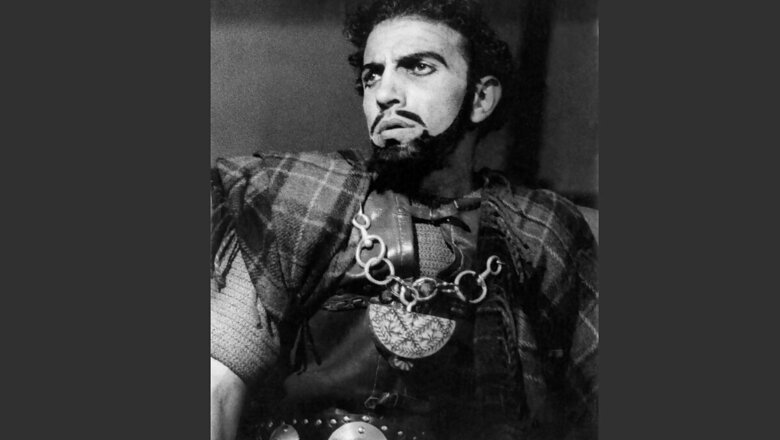

In his fifteen years spearheading NSD, he created a well-formulated teaching programme and a formidable reputation as an actor trainer. For the initial seven years as Director, NSD, along with his trail-blazing Ashad ka Ek Din and Andha Yug, my father did new productions of plays he had directed earlier: Sophocles’ Oedipus, Strindberg’s The Father, Ibsen’s Ghosts, Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, Anouilh’s Antigone, Moliere’s The Miser and Scapin, this time around in Hindi or Urdu. These are all theatre ‘classics’, staple fare in acting institutions across the world.

For the next seven years he vitalized the school’s curriculum by inviting directors from elsewhere to interact and work with the students. From Germany came directors Carl Weber and Fritz Bennewitz to introduce the genius of Bertolt Brecht to Indian audiences, while from Japan Professor Shozo Sato directed an impressive Om Puri in the titular role of a Kabuki play in Hindi, Ibaragi. Along with these was a trail of plays by emerging Indian playwrights, many appearing on the stage immediately after being written.

NSD at the time mounted rivetting productions in the folk form of Gujarat, bhavai, in Shanta Gandhi’s Jasma Odan and B.V. Karanth’s Yakshagana rendering of Veer Abhimanyu. Vernacular theatre traditions from different corners of India were beginning to enter mainstream urban culture. Within a few years, NSD graduates returned to explore their own roots, whether in Manipur with Ratan Thiyam or in Karnataka with Prasanna among others. Sanskrit theatre traditions were explored in Madhyam Vyayog, Shakuntala and The Little Clay Cart.

Ebrahim Alkazi and Roshen Alkazi née Padamsee (later Alkazi) on their wedding day in October 1946. Photo courtesy: Alkazi Theatre Archives

When he left NSD in 1977, my father went out in a blaze of light, mounting three huge productions in the Purana Quila Theatre that he had designed. As the blue leached out of the Delhi summer sky, and a heavy purple twilight descended, the jewel-like tones of my mother’s costumes appeared against the weathered stones of Purana Qila. Here, as the distant roar of lions from the nearby Delhi Zoo could be heard, the tragic tales of Razia Sultan and Muhammed Bin Tughlaq were played out. A long flight of steps led down from a huge archway that was sometimes filled by the ceremonial procession of a king, and at other times resounded to the clash of swords as Razia Sultan battled for her life and yet at other times was full of the rushing, rioting mobs hungry for food in Girish Karnad’s Tughlaq. Delhi’s history came alive at Purana Qila.

The third play to be mounted here was Andha Yug, now in a completely new production avatar, fourteen years after it was first seen at Feroz Shah Kotla in 1963. Inspired by the stylized movement of Yakshagana and Kabuki, the universal theme of the futility of war set after the Mahabharat battle was performed with the grace of a dance to a sung chorus composed by Vanraj Bhatia. To clothe the characters in this new interpretation, my mother drew on Japanese and Indian garments accompanied by Yakshagana-style headdresses and make-up.

From these large, sweeping, spectacular productions that still inhabit the imagination of Delhi audiences to the small, intimate, emotionally heavy world of Jimmy Porter and Alison in John Osbourne’s Look Back in Anger played out in the studio theatre of the NSD, my father had demonstrated his prowess over several genres of drama.

His thorough grounding in aesthetics and theatre in England and Bombay had borne fruit and nurtured several generations of theatre workers, on and off stage, in rural and urban India, creating a national theatre movement. At its apex, at least in those years, stood the NSD. Very few other national institutions ever gained that stature.

Interestingly when he left, he selected B.V. Karanth as his successor, a person completely unlike himself in background, exposure, personality and outlook. Karanth, an ex-student of NSD, had worked in a commercial theatre company in Karnataka, learnt classical music in Varanasi, then used his NSD training to break new ground in theatre and cinema. He was to lead NSD in a very different direction. In a similar fashion my father had left Theatre Unit in the hands of Satyadev Dubey in 1962 when he moved to Delhi, again an immensely talented individual with a very different ‘take’ on the world.

As Neelam Mansingh, one of NSD’s star alumni and an eminent director, was to write years later, ‘Both Alkazi and Karanth not so much created a revolution as they put stakes in the ground, drew a boundary… created a new planet, where theatre artists could come and discover their own beings in a mixture of rational, creative, historical and traditional ways.’

(All photos courtesy: Alkazi Theatre Archives)

Read all the Latest News, Breaking News and Coronavirus News here

Comments

0 comment