views

What do women want? Where are their voices? What does it take for women to be heard? Sometimes, it’s a lifetime, and sometimes, tragically, it’s death.

History is a canvas, and politics the palette of colours within that historical painting. Sadly, for the women of Afghanistan, the brush that paints their history is not wielded by women. If Afghan women had a voice, their history would be rich with their representation and their stories. Unfortunately, extremist ideologies, disguised as religious mandates, are responsible for silencing Afghan women in the global public sphere.

This analysis comes after reading the recent statement made by the Taliban-led Afghan government envoy at the recently held UN meeting with Afghanistan’s Taliban government in Doha. The Taliban has used its interpretation of Islamic law to bar girls from education beyond age 11, ban women from public spaces, exclude them from many jobs, and enforce dress codes and male guardianship requirements. Please correct me if I am mistaken, but shouldn’t a delegation be dispatched to assess the actual situation of women in Afghanistan? The internationally scattered Afghan intelligentsia and youth should rise to voice against the subjugation and human rights violations of women in their homeland.

The Taliban government, which has enforced severe restrictions on women since seizing power in 2021, actions the UN has labelled as “gender apartheid”, claims to not include women in its representation or even in any public engagements. The reason given by the Taliban is religious sanctions on women. Any sound mind, even a religious person, will clearly understand that no religion—not even the one the Taliban prides itself on following—sanctions anti-human rights or anti-women rights.

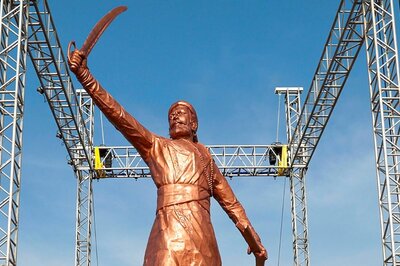

While in the Arab world, Bibi Khadija, a businesswoman and a widow, proposed marriage to the Prophet Muhammad. Generations later, after the assassination of the Prophet’s grandson, Imam Hussain, and his companions in Karbala, it was Bibi Zainab—sister of Imam Hussain and granddaughter of the Prophet—who bravely led their family against the tyrannical ruler Yazeed. If not for Bibi Zainab’s courage and eloquence, the message of truth, love, non-violence, and equality that were at the heart of the battle of Karbala might have been lost to history.

All the anti-woman policies and decisions of the Taliban and similar groups worldwide appear to be a human-created subjugation of women. In the Islamic world, women established the first university. This and many more examples from Islamic narratives speak to the existence of smart, intelligent, and successful women throughout history. The concept of religious morality being solely placed on women’s shoulders, as well as the burden of religious purity, is not a genuine religious sanction. Rather, exploring the historical and sociological context reveals a clear pattern of intentionally curtailing women’s rights and denying them basic human rights. The UN rightfully terms this “gender apartheid.”

Picture this: subjugated women celebrating a man’s victory to the highest office, their celebration fuelled by the hope that their own oppression might now find some relief. This recent image reflects a nation that even dictates what women should wear. Throughout history, women and their roles in leadership or public life have faced constant scrutiny and criticism. During the Mughal era, efficient princesses rarely emerged to rule; many died unmarried as they were prohibited from marrying outside the Mughal household. Meanwhile, Mughal men justified and glorified their matrimonial alliances outside the Mughal clan.

So, while the Taliban declare the absence of women from their own basic choices in life and public spaces, this phenomenon resembles a social infanticide of women. No stories of women are factually correct unless told by women; the pain of not wearing what they wish, not dressing as they choose, or not even voicing their pain is the greatest bankruptcy of any civilisation, country, or nation. History teaches and documents many such practices that have kept women away from mainstream human civilisation. Even if a woman is well-trained in statecraft and military tactics like Razia Sultan, her candidacy is criticised, and she has to face gender apartheid in the 12th century.

Recent social fabrics of many nations have seen some progressive measures in the context of women’s policy decisions. The most recent has been in our Bharat. The Supreme Court of India’s judgement, Mohd Abdul Samad vs The State of Telangana, has upheld the rights of divorced Muslim women to claim maintenance under Section 125 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), 1973. This Act created a new right for divorced Muslim women to claim maintenance during the iddat period as well as a fair and reasonable provision for the future.

It is important for the Muslim community to confront entrenched patriarchal mindsets and embrace the evolving, pro-women systems emerging in legal frameworks and broader society. While many Muslim nations demonstrate progressive approaches to women’s empowerment, some groups remain fixated on criticising and obstructing positive change. It is vital that the Muslim community, along with dissenting voices within and beyond, loudly and unequivocally condemn such backward practices.

If Mughal emperor Akbar could challenge the practice of Sati and support widow remarriage, if Ishwarchand Vidyasagar could champion women’s education, and if Sir Syed Ahmed Khan could establish a major education hub, prioritising girls’ education despite facing intense backlash from within his own community, there should be no hurdles or hesitation in today’s social fabric and communities to stand against these kinds of gender apartheid practices.

Dr Syed Mubin Zehra is a Historian, Academician and a strong voice on gender and human rights. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely that of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

Comments

0 comment