views

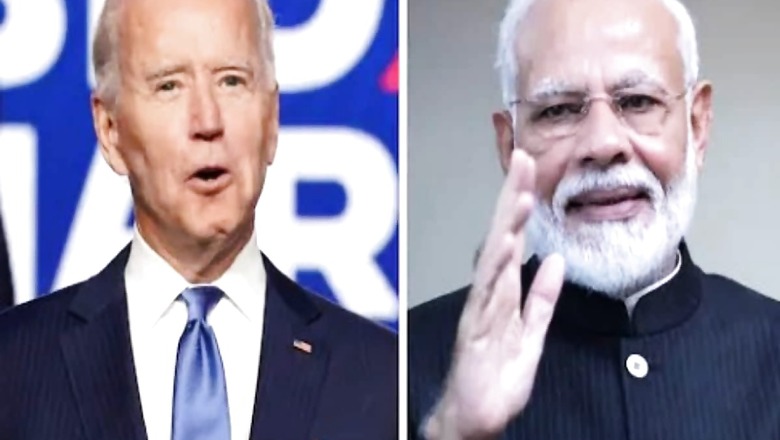

US President Joe Biden recently unveiled his $2.3 trillion infrastructure plan centred on fixing roads and bridges, expanding broadband internet access, funding more for research and development (with a special focus on research for ‘renewable’ energy led production capacity) in the country. He aims to finance this package through a higher corporate tax base where more profitable corporations would need to add more to the federal tax base. Biden has called this plan a “once-in-a-generation investment in America”.

The spirit of this massive spending plan in the United States seems—at least in its projected direction—similar to what finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman was hoping to project before her “once in a hundred years” budget back in February. Her budget outlay too highlighted a larger focus for greater infrastructure spending, albeit, the details of the plan—in both planning and execution— remain unclear till this very day.

Taking a step back, for anyone writing on issues of economic policy over the last few decades, it is vital to see how the mainstream economic policy view in any nation state’s economic policy apparatus remains more skewed in favour of a neoliberal-economic consensus led by the United States. What we are witnessing now, under Biden, is another structural shift away from neoliberalism towards the remaking of a new consensus.

A neoliberal economic consensus, traced back to the “Washington Consensus” of the late 1980s, in its core elements relied upon: low levels of government spending, a considerably high focus on minimising (fiscal) deficits, liberalisation of trade and foreign investment, and an unshakable trust in (free) unregulated markets to resolve all economic woes.

Biden’s economic plan— one can label it as “Bidenomics”— marks a fundamental shift away from this neoliberal package.

In its thought and action plan, Bidenomics relies on: a high government spending plan based on infra-based (re)building projects for job creation (under Biden’s “Build Back Better” slogan); more spending on public goods (healthcare, education, job security, childcare); less regard for (fiscal) deficits that is inspired from a Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) led economic thought that argues higher (fiscal) deficits do not crowd out private investment; a clear emphasis on income support for the most vulnerable at all times (not just in a moment of crisis), and, a more critical view on unregulated markets, where any form of monopoly power and check on market entry of firms exercised by big corporations, need to be checked and brought in line.

Though from a closer review, it is still not clear whether key elements of this new consensus qualify it to be part of a new political thought in motion— supported by those on the political left— or if it is likely to evolve as an independent economic thought/consensus over time (as seen with the Washington Consensus).

A critical approach to neoliberal economics was evident in Donald Trump’s politics too, but that remained circumscribed to political rhetoric that never actually translated into a concrete economic plan that could work for all Americans. ‘Bidenomics’ changes that by being the new political economy vision that the US and much of the developing world too needs. It is customised in principle to address the politico-economic and socio-economic realities of our times.

More importantly, given the unique position of America as a global political and economic actor, if successful, Bidenomics can change the game in the economic policy design architecture for most developing countries too, including India, where structural economic concerns remain quite similar to the US at this point: high inequities, unemployment, low productivity and low aggregate demand, accompanied with a low spending base on public goods, to mention a few.

In India’s own economic policy framework (if there is one), however, ‘Delhi’s Economic Consensus’, entrenched in the ministry of finance’s complex bureaucratic web, remains quite distant and divergent from all that Bidenomics represents. One illustration of this is how economic policymakers in India have been addressing a chronic aggregate demand-side economic crisis—one that was bad enough before a pandemic—through a purely supply-side plan, even now.

The analytical framework of any sustainable form of government spending plan over a medium to long term isn’t still there, nor seems to be on the horizon. Our technocrats too are obsessed with the management of fiscal deficit levels at a time of a major crisis—the worst since Independence— when spending on healthcare capacity, job creation, economic security for the most vulnerable should be prioritised on a war footing. And, above all, the unfettered rise in monopoly power seen for more profitable, big corporations across sectors is unchecked.

How may this failed economic thinking impact us? The same way neoliberalism —in its aspirational economic thought and action— wreaked havoc in parts of both the developed and developing world over the last few decades, and quite contrary to the hope of bringing progression in growth, destroyed social safety nets for the poor. The rise of right-wing populism in the US —under Trump— and in most of Europe was causally linked with the pre-existing state of economic deprivation created from the chronic failures of neoliberal economic policies.

India too saw a widening of wealth-income inequities during the 1990s (when a neoliberal pro-market plan was put in motion) and saw lowering growth in middle-income real wages, while subsequently witnessing a structural breakdown in employment-led growth across sectors. Now, a similar scenario, with far longer consequences due to a more socially divisive political economy, is surfacing, unless a new radical, political economy vision, aligned with Biden’s politico-economic plan, can find a way across to New Delhi.

Read all the Latest News, Breaking News and Coronavirus News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Telegram.

Comments

0 comment