views

If you ever get to have a conversation with Shashi Tharoor and don’t have a dictionary, well pray. The Parliamentarian is most specifically recognised for his favouritism in using polysyllabic behemoth words that are quite incomprehensible even to the most scholarly minds. Try saying floccinaucinihilipilification in the next conversation.

That is something he did once and it led the whole nation to Google searching. The Congress MP can even break the thesaurus into cold sweat. But if you want to be an etymological egghead like him, Tharoor suggests to continue reading books although with one caveat.

During the launch of his book, A Wonderland of Words, Tharoor advised people to read more for better English. According to Money Control, he noted that one can learn a lot in the process of reading for pleasure.

Drawing from the experience, Tharoor described how he once read 365 books in a year out of zeal but warned that he would never do it again, the publication reported.

Here’s what stands out in his book:

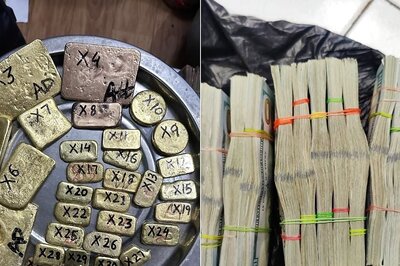

In his essay, Words about Money, he makes a correlation between numerous English terms associated with money and words in the Inuit language that refer to snow. By drawing this analogy, Tharoor suggests that the languages used by the Inuit people have a wide vocabulary to characterise various forms and phases of an important component of their environment—in this case, snow. That being said, there is a large vocabulary in the English language for describing money. He gives examples including, aid, allowance, alimony, bills, bribes and budget, among others.

He can come up with quotations from Shakespeare and use words that reflect contemporary society. For example, he clarifies that the correct spelling of the word is “OK,” which had its roots in the etymological joke that American journalists made in the 1830s where they wrote “oll korekt” meaning all correct.

In the essay, The Significance of Slang, he described how certain words like “cool” remain effective while using what is now considered old and “groovy”.

There is always a tinge of autobiography in Tharoor’s essays. He recalls his time in the UN where they had documents called “non-papers,” which are white papers without the legal backing of a paper; this way, the bearer does not have to withdraw it ever.

Tharoor also shared an anecdote of speaking to Pakistan’s General Pervez Musharraf at the United Nations. At an event where Musharraf was to make a speech the topic of discussion was the effect of the India-Pakistan conflict and described the situation in the region as a case similar to taking two elephants to fight when the grass gets stepped on, meaning the small neighbouring countries. Tharoor jokingly remarked that even if elephants make love, the grass gets stepped on.

In The Language of Elections, he gives a brief etymology of such terms as election, electorate and candidate. He concludes with a playful vote between suffrage and suffering and observes that though the two words are not synonyms when a wrong candidate is elected, suffering is the outcome.

The essays featured in A Wonderland of Words are classified chronologically to examine different clusters of words about time, its meanings, origins and humour.

Comments

0 comment