views

China’s Four Great Folktales

Butterfly Lovers Zhu Yingtai was a smart and pretty girl who loved to study, but women weren’t allowed to go to school at the time. She disguised herself as a boy to attend classes and meets a boy named Liang Shanbo, and the two quickly become “brotherly” friends. When Zhu is ordered to return home by her father 3 years later, she drops hints to Liang about her identity and promises to arrange a marriage between him and her “sister.” Liang arrives at Zhu’s home to discover that she is, in fact, the sister. Unfortunately, it’s too late—Zhu’s father has arranged her marriage to a man named Ma Wencai. Liang returns home, falls ill, and dies. Before going to Ma’s home, Zhu insists on mourning Liang at his tomb. While she’s there, a bolt of lightning cracks the tomb open. Seizing her chance, Zhu jumps into the tomb before it closes. Soon afterward, two butterflies were seen leaving the tomb, fluttering away like a pair of lovers. The myth is considered foundational to Chinese folklore and is known affectionately as the “Chinese Romeo and Juliet.”

The Legend of the White Snake In the beautiful city of Hangzhou, famous for its lake, a white snake demon named Bái and her sister lived in the lake. She had magical powers and could turn herself into a human, and she soon fell in love with Xu Xuan, a poor and naive herbalist. The two were married, but a priest named Dharma Sea, who lived at the Golden Mountain Monastery, deemed Bái a danger. He warned Xu about her true nature, but when Xu and Bái stayed together anyway, he took matters into his own hands and kidnapped Xu to protect him. Bái and her sister went to Monastery and battled Dharma Sea for Xu’s release, but were unsuccessful. However, Xu managed to escape on his won during the fight and reunited with Bái. Bái confessed everything to Xu, including the fact that she was due with his child soon. Xu was still in love with her after everything, and the two remained together and raised a beautiful baby boy. Dharma Sea once again tried to capture Xu, but was thwarted by Bái’s sister Xiǎoqīng, who learned the necessary martial arts to defeat the monk for good. One of the most well-known myths in Chinese culture, this tale symbolizes the universal theme that love conquers all.

Lady Meng Jiang Under the rule of Qinshihuang, the first emperor of the Qin Dynasty (221–207 BCE), Lady Meng Jiang's husband was forced to participate in the construction of the Great Wall of China just 3 days after they were married. After months went by without hearing from her husband, Meng Jiang set out to find him at the Great Wall. She was heartbroken to learn that he had died during construction and was buried under a segment of the wall, along with thousands of other workers. Legend says that Meng Jiang wept profoundly for 3 days and 3 nights, eventually causing a portion of the wall to crumble and reveal her husband’s remains. This myth is one of China’s oldest narrative stories and is one of the most famous folktales from the country.

The Cowherd and the Weaving Maid Zhīnǚ was a beautiful Weaving Maid in the celestial palace of the Queen Mother of the West. One day, Zhīnǚ and her six sisters visited the Earth to bathe in a refreshing stream when they were spotted by a handsome but very lonely cowherd named Niúláng. He was transfixed by their beauty and picked up the clothes that one of them had left on the riverbank. Zhīnǚ’s sisters fled in fear, but Zhīnǚ stayed to retrieve her clothes from Niúláng. The two fell in love, Zhīnǚ decided to stay on Earth, and they had two children together. After some time had passed, the Queen Mother of the West ordered her troops to capture Zhīnǚ and bring her home, separating her from Niúláng and their children with the Milky Way running between them like a river in the sky. Niúláng, Zhīnǚ, and Zhīnǚ’s sisters wept and pleaded with the Queen Mother to reunite them. Eventually, she took pity on them. The lovers and their children were allowed to reunite on the seventh night of the seventh month of every lunar year by crossing a magical bridge of magpies that spans the Milky Way.

More Important Chinese Myths

Pangu and the Creation of the World In Chinese lore, the universe was created when the god Pangu (Pan Gu) cracked the egg he was sleeping in. The egg contained both Yin and Yang; Yang rose to create the sky and heavens, while Yin formed the earth. Pangu used his hands and feet to hold Yin and Yang in their proper positions for 18,000 years. When Pangu died, legend says his body parts transformed into the natural features that made the Earth. For example, his head is said to have become mountains, his blood rivers, his muscles into fertile land, and his bones into valuable minerals.

Sun Wukong the Monkey King Sun Wukong is a trickster god and possibly the most famous monkey from Chinese mythology. Known as the King of the Monkeys and with the powers of super strength and physical transformation, Sun Wukong was invited to live in the heavens with the other gods before his temper and desire to rule caused the Buddha to intervene and trap him under a mountain for 500 years. Eventually, a monk named Tang Sanzang found and released Sun Wukong on the condition that he repent and help the monk retrieve sacred texts from India. Sun Wukong reluctantly agreed and battled many demons on the journey, eventually earning his redemption and achieving enlightenment.

Chang’e and Hou Yi Folk hero Hou Yi, who shot down 9 extra suns that were boiling the earth, was gifted the elixir of life by the Queen of Heaven. However, there was only enough potion for one person, and Hou Yi did not want to become immortal and separated from his wife, Chang’e. One day while he was away, one of Hou Yi student’s Feng Meng, tried to steal the potion while Chang’e was guarding it. Knowing she couldn’t defeat Feng Meng, Chang’e drank the potion. She was instantly transported to the moon to watch the world, where she still remains to this day. When the moon is brightest during the Chinese Moon Festival, legend says you can still spot her on the lunar surface.

The Jade Rabbit One day, the Jade Emperor (the supreme deity in Taoism) sought the help of animals in creating the elixir of life. He disguised himself as a beggar and requested food and help from a monkey, a fox, and a rabbit. The monkey provided fruit, the fox provided fish, but the rabbit was unable to procure anything to help the beggar. Realizing he could sacrifice himself to feed the beggar, the rabbit attempted to hop into his fire. However, the Jade Emperor revealed himself and stopped the rabbit from meeting a fiery fate. Recognizing the rabbit’s noble act, the Emperor carried him up to the moon, where he worked hard to create divine medicines, including the elixir of life. The Jade Rabbit is also known as Chang’e’s lunar companion. Fun fact: Modern Chinese astronomers often name their spacecraft after mythological figures. One of these includes a lunar rover named Yùtù (玉兔), named after the Jade Rabbit. The rover is part of the Chang-E 3 lunar mission, named for Chang’e.

The Dragon Dragons are the most powerful and divine creatures in Chinese mythology, often symbolizing luck, good fortune, and the emperor. According to one legend, the Yan Emperor Yándì (炎帝) was born of an encounter with a powerful dragon, making him one of the most powerful rulers alive. He conquered China’s enemies, unified the country, and pioneered ancient Chinese civilization. According to the myth, Yándì is an ancestor of the Chinese people, meaning that they are also descendants of dragons. The earliest dragon symbols date back to around 3000 BCE and may originally have been a combination of attributes from more common animals like tigers, snakes, eagles, and carp. Yándì is also known as the Emperor Huang Di, or the mythical Yellow Emperor. According to legend, he turned into a dragon and flew into the heavens when he died.

Guardian Lions A pair of protective lions (one male and one female) is a fixture in Chinese architecture, design, and folklore. Believed to bring luck and exorcise evil spirits, the male lion is often shown with a ball (representing the Earth) while the female lion is holding or protecting a lion cub (representing nature and generations). Lions are not native to China and were introduced during the Western Han Dynasty (206 BCE to 9 CE) when the diplomat Zhang Qian travelled to Central Asia. They soon became a major theme in sculptures afterward. Lion pairs are often placed in palaces, tombs, gardens, and residences for protection.

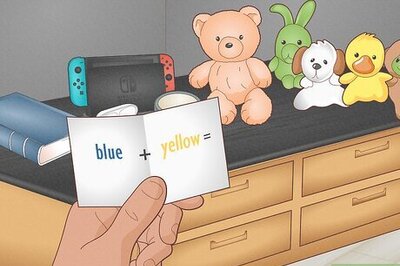

The Creation of the Chinese Zodiac One day, the Jade Emperor announced a race for all animals to determine which 12 would fill the Chinese zodiac. The rat, who was friends and neighbors with the cat, was supposed to wake the cat for the race, but forgot. The rat rode on the back of the ox, who was running in front of the pack. When they neared the finish line, the rat leapt off the ox’s back and finished in first place, becoming the first sign in the Chinese zodiac. The ox finished second, followed by the tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, goat, monkey, rooster, dog, and pig. The cat arrived too late to compete and was not included in the zodiac. According to legend, this is why cats hate rats so much (and always try to kill them). Another version of the legend says that both the rat and cat were riding on the ox, but the rat shoved the cat off of the ox and into a river to outcompete her.

Nian and the Legend of the New Year There once was an ugly, terrifying monster named Nian who regularly came down from the mountains to feast on humans. Villagers were so afraid of Nian that they would lock themselves in their homes for days when they knew the creature was coming. One day, a wise old villager suggested that everyone band together and chase the monster away with loud drums and fireworks. The plan worked. Nian ran away from the villagers until he was completely exhausted, and the villagers were finally able to kill him. According to myth, this is how the first Chinese New Year celebration started (“Nian” means “year” in Chinese). In some versions of the legend, the old man is a celestial being sent to help the villagers defeat Nian.

The Three Sovereigns and the Five Emperors This myth explores the earliest rulers of China who existed long before the first Chinese dynasty. The Three Sovereigns were demigods who taught the early Chinese people important skills for survival. Fu Xi invented fishing, trapping, and writing, while his sister Nu Wa helped Fu Xi create humans and repaired the wall of heaven. Shennong (“Divine Farmer”) invented the plow, axe, hoe, irrigation, the Chinese calendar, and the practice of farming. The Three Sovereigns lived extremely long lives and ruled over a period of prolonged peace. The Five Emperors, considered to be morally perfect, included The Yellow Emperor Hunag Di (黄帝), Zhuanxu (顓頊), Emperor Ku (帝嚳), Emperor Yao (堯), and Emperor Shun (舜). They ruled after the Three Soverigns, up to the beginning of the Xia Dynasty (c. 2070 BCE). These legendary Emperors were considered model rulers and were revered by later Confucians as morally ideal. It’s said that Yao and Shun, known as The Two Emperor’s, were exceptionally moral and co-founded the Xia Dynasty along with Yu the Great.

The Four Guardians The Four Guardians (or Symbols or Gods) of Chinese myth are the Azure Dragon (Lesser Yang), Vermillion Bird (Greater Yang), White Tiger (Lesser Yin), and Black Tortoise (Greater Yin). They symbolize a more nuanced understanding of Yin and Yang, or the opposite but balanced forces that shape the world. Each Guardian is also assigned a cardinal direction and element to oversee: The Azure Dragon symbolizes the East (left), the element wood, and the season spring. The Vermillion Bird represents the South (front), fire, and summer. The White Tiger governs the West (right), metal, and autumn. The Black Tortoise rules over the North (back), water, and winter. Some versions of the legend also say that the Yellow Dragon (the Yellow Emperor Hunag Di) rules the center and the element of earth.

The Legend of Mirrors Ancient Chinese people believed that your reflection wasn’t really you—it was actually a demonic species learning how to mimic your behavior with the goal of one day breaking free and ruling the Earth. According to legend, the Yellow Emperor Huang Di went to war against the mirror creature in 2697 BCE after they escaped and tried to take over humanity. The Yellow Emperor managed to lure the creatures back into the mirror world, but only temporarily. It’s said that the mirror creatures will break free again one day—and next time, they’ll be successful.

Mythical Deities, Creatures, and Heroes

Major gods and goddesses Chinese folklore is full of gods, demigods, and celestial beings who shaped the Earth—and the fate of humanity—in many tales and legends. Here are some of the most prominent deities in Chinese myths: Bixia: Goddess of fertility, guardian of children and mothers Caishen: God of wealth and money whose cudgel turns iron into gold Chang’e: Goddess of the moon Changxi: Lunar goddess and mother of the Twelve Moons Dianmu: Goddess of lightning, married to Lei Gong (the thunder god) Di Jun: Ancient Chinese emperor married to the sun goddess and moon goddess Doumu: Cosmic goddess and mother of the Big Dipper constellation The Dragon King: God of all waters, weather, and dragons The Eight Immortals: Legendary heroes who fight for justice and defeat evil Erlang Shang: God of engineering, a great warrior with an all-seeing third eye Fu Xi: Humanity’s original ancestor (brother and husband of Nuwa) Guanyin: Goddess of mercy Huxian: A fox fairy and bringer of seductive wealth and moral ruin The Jade Emperor: The supreme ruler of heaven Jiutian Xuannu: Goddess of war, sex, and longevity Lei Gong: God of thunder who punishes evildoers (human and demonic) Lu Ban: God of carpentry, builders, and contractors Mazu: Goddess of the sea, sailors, fishermen, and travelers Menshen: Door gods that guard buildings against demons Nezha: Deity who protects teens, misfits, and drivers Nuba: Goddess of droughts, daughter of the Yellow Emperor Nuwa: Goddess who created mankind, sister and husband to Fu Xi Pangu: The first living being who created the world Sanguan Dadi: The imperial officials of sky, earth, and sea who judge humanity Shennong: The farmer god and founder of agriculture Sun Wukong: The “Monkey King” and a trickster god Wenchang Wang: Deity of literature and culture Xihe: Solar goddess, mother of the destructive 10 suns Xiwangmu: The Queen Mother of the West, goddess of life and death Yan Wang: The King of Hell and judge of the dead Yue Lao: God of love and marriage Yu Shi: Rain deity Zao Jun: Stove god who watches over the home and family Zhong Kui: A demon hunter god who fights ghosts

Notable mythical creatures Chinese folklore includes many animal and creature characters—some inspired by real animals, and some that are totally mythical. These include dragons, fish and fish-like creatures, snakes and snake-like creatures, birds, humanoids (human-looking creatures that are only part-human or demonic), as well as lots of mammal spirits including foxes, dogs, bovines, ox, sheep and goats, horses, unicorns, cats, and monkeys. Here are some of the most popular and enduring mythical creatures: The Qílín: A dragon-like creature that symbolizes good luck and prosperity (it has a single horn on its head like a unicorn) Jiǔwěihú: A nine-tailed fox spirit that can shape-shift and be both good or evil Shāngyáng: A rain bird that predicts the onset of rain when it dances on one leg The Jiāngshī: Reanimated corpses (similar to zombies or vampires) that feed on the living The Xièzhì: An ox-like creature that symbolizes justice and can communicate with humans The Jiāorén: Creatures with human-like upper bodies and tails instead of legs, similar to mermaids

Important folk heroes and human characters Many prominent Chinese folk heroes and heroines exhibit qualities similar to the Confucian Eight Virtues (loyalty, filial piety, benevolence, love, honesty, justice, harmony, and peace), making them ideal people to venerate in mythology. Some legendary figures and heroes you’re likely to hear about include: Ji Gong (the “Mad Monk”): Folk hero who champions the poor and oppressed Cangjie: Creator of the Chinese writing system Chiyou: A tribal leader, formidable warrior, and inventor of weapons Gun: Father of Yu the Great (founder of the Xia Dynasty) Hou Ji: Legendary farmer who introduced millet to humanity Hou Yi: Legendary archer who shot down 9 suns Hua Mulan: Folk heroine who disguises herself as a man to take her father’s place in the military Ji Gong (Daoji): A Buddhist monk who used his superpowers to help the poor Wenshu (Bodhisattva Manjushri): The embodiment of wisdom and protector of sacred knowledge Yue Fei: Military hero who defeated the invading Jin forces Liu Bei: A humane, benevolent, and compassionate ruler Zhang Fei: A strong, loyal, and brave warrior Cao Cao: A power-hungry ruler and nemesis of Liu Bei, although he is viewed as both a hero and villain Zhuge Liang: A loyal, wise, and brilliant military strategist

Characteristics of Chinese Mythology

General themes on nature and world creation from chaos Like in many cultures, the creation of the world out of chaos is a major theme in Chinese folklore (highlighted by stories such as Pangu and the Creation of the World). The importance of nature and explanations for heavenly bodies, like the sun, moon, and stars, also feature prominently. Tales like The Creation of the Zodiac, Hou Yi and Chang’e, and The Cowherd and the Weaving Maid all explore ideas of celestial bodies being created and human interactions with the natural world. Other recurring themes include: Reverence for ancestors Aging and the pursuit of wisdom, enlightenment, or immortality Relationships with or the importance of animals like dragons, pigs, and monkeys

Confucian, Taoist, and Buddhist influences Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism are the “three pillars” that shaped Chinese mythology (as well as ancient and modern Chinese societies) the most. These belief systems overlap in some teachings and blend together rather than competing for ideological or mythical dominance. Influences from all three philosophies and religions can be found in ancient myths, and it’s believed that some ancient myths may have shaped the philosophies as well. Confucianism emphasizes the teachings of Confucius (551–479 BCE), which impacted interactions between family members and in the public sphere, educational standards, and how states should be governed. Familial respect, hierarchies, and self-discipline are all Confucian traits that appear frequently in Chinese myths. Taoism (Daoism) is a religion that appeared shortly after Confucianism. The Taoists believed in the natural world and medicine, longevity and the pursuit of wisdom, and the balance of Yin and Yang— all elements of Chinese myths. The Taoist pantheon, including deities like the Jade Emperor, also impacted Chinese folklore. Buddhism arrived in China in the sixth century BCE. Its focus on personal development and enlightenment is evident in several myths, and figures like the Buddha appear in some folktales (like Sun Wukong the Monkey King).

Frequently Asked Questions: Chinese Mythology

What is the oldest Chinese myth? Chronologically, the legend of Pangu and the Creation of the World is the oldest Chinese myth since it describes the very formation of the universe. However, dragon symbols dating from as far back as 3000 BCE indicate that myths and legends about dragons may be some of the oldest Chinese folklore we know of. Most ancient Chinese myths were passed down orally, making it difficult to say with certainty which one is truly the oldest.

What are the four mythical creatures of China? The four mythical creatures of China are the Azure Dragon, Vermillion Bird, White Tiger, and Black Tortoise. They’re also known as the Four Symbols, Four Guardians, or Four Gods and are important Chinese symbols today. These legendary creatures represent foundational aspects of Chinese beliefs and society, and may be more responsible for shaping Chinese cultural identity than any other collection of deities or mythical figures. Today, the energy of the Four Guardians is often used in feng shui to set up auspicious home and business spaces.

What are China's four great folktales? China’s “Four Great Folktales” include The Butterfly Lovers, The Legend of the White Snake, Lady Meng Jiang, and The Cowherd and the Weaving Maid. These are some of China’s oldest, best-known, and most influential folktales, exploring broad, universal themes like the triumph of love and the rewards of persistence. They’re considered foundational to China’s mythological fabric and are still culturally relevant today.

Who is the most powerful figure in Chinese myth? The Jade Emperor is the supreme deity in the Taoist pantheon and is considered the most powerful mythical being in Chinese folklore. In some legends, he is considered to be the only singular force capable of conquering evil. While the Jade Emperor may be the strongest god, the Buddha is considered the most powerful being and outranks the Jade Emperor from a Buddhist perspective (the Buddha is not technically a god, so cannot be considered a powerful deity in the same sense).

Comments

0 comment