views

Gathering Your Supplies

Make sure you have an IV stand. The IV stand is the tall pole with a coat hanger-like device that you will hang the IV bag on when you are preparing and administering it. In case you can’t find an IV stand and it is an emergency, your will have to hook the bag up to a place that is above the patient’s head, so that the force of gravity helps the liquid to flow downward into the person's vein. Most hospitals now have IV machines, which include the pole and hanger.

Wash your hands. Turn the faucet on and lather your hands with soap and water. Start with your palms and work to the back of your hands. Make sure that you also clean the areas between your fingers. The next step is to focus on washing from your fingers to your wrists. Finally, rinse thoroughly and pat your hands dry with a clean paper towel. Observe "clean" procedures until you don gloves. If there is no water source, rub your hands with an alcohol-based hand sanitizer.

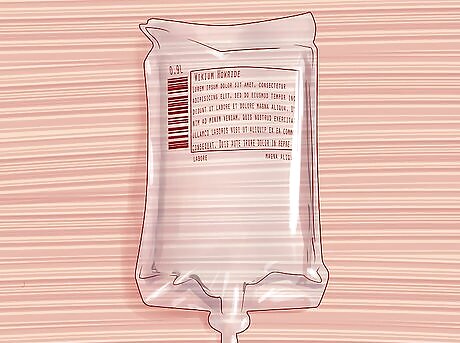

Double check the doctor’s orders again before you begin. Gather the correct IV bags, including amount of fluid and type of fluid. (The materials are collectively called an IV administration set, which includes the tourniquet, needle, IV tubing, bag(s) and all incidental items needed, such as alcohol wipes, gauze, tape, etc. ) Giving a patient the wrong IV bag could lead to a life-threatening situation, such as an allergic reaction. Giving incorrect amount or type of fluid or IV-medication is also against The Nurse Practice Act. At minimum, an R.N. can be written up for any errors. Note and Locate bag size you need. Usual bag size in hospital setting is 1,000 ccs which is run over a specific period of time. (See order.) However, an IV comes in ccs of 1,000 ; 500 ; 250 ; 100 ; and for administration of IV-medications, cc bags of 50 or 100 which is referred to as a "IV piggyback" (IVPB), while a continuous larger bag IV is referred to as the primary IV. If placed in a peripheral vein, it is a peripheral IV, while an IV attached to a central port is a central IV. Note and Locate the type of fluid needed. The most common orders can include one of these: water W (this indicates sterile water) ; dextrose (Dex); saline (S) (e.g. normal saline); normal saline (NS) ; Ringers Lactate/ Lactated Ringers (RL or LR) ; potassium chloride. Note any percentage given in the order for the type of fluid. Some percents are standard in the industry, but you must still always make sure you pick the correct percent listed on the bag that matches the order. Make sure to get any labels that you need to fill out and adhere to the IV bag. Double check that you are giving the medication to the right patient, that you are doing it at the right date and time, that you are giving the correct medication in the correct order, and that the bag is the right volume. Redo these steps at bedside. You must redo these steps even though you checked these facts already. Always re-verify at bedside. If you have any questions at all, it is important that you ask your supervisor before continuing so that you are 100% sure you understand what you are supposed to do. Consult the physician or on-call doctor if you question the order itself.

Micro Details

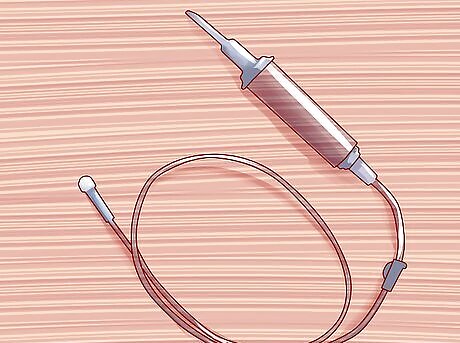

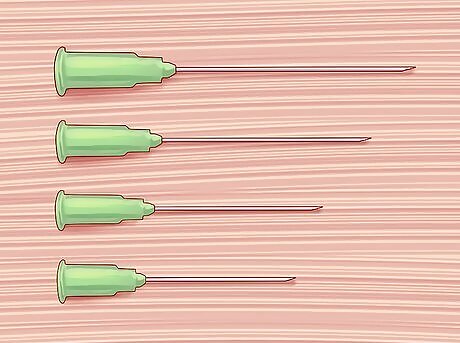

Determine beforehand what kind of set you will need to use. A set is the tube and connector that regulate how much fluid the patient will get. A macroset is used when you are supposed to give the patient 20 drops per minute, or about 100 mL per hour. Adults generally receive a macroset. A microset is used when you want to give the patient 60 drops of IV fluid per minute. Infants, toddlers, and younger children generally need a microset. The size of the tubing (and the size of needle) that you use will also depend on the purpose for the IV. If it is an emergency situation where the patient needs fluids as quickly as possible, you will more likely choose a larger needle and tube in order to deliver the fluids and/or blood products or other medications as quickly as possible. In less urgent situations, you may choose a smaller needle and tubing.

Get the right size of needle, called the needle's gauge. The higher the needle gauge, the smaller the size of the needle. Size 14 gauge is the largest and it is usually used to correct symptoms of shock and trauma. Size 18-20 is the usual kind of needle used by adult patients. Size 22 is usually used on pediatric patients (such as infants, toddlers, and young children) or geriatric patients with .

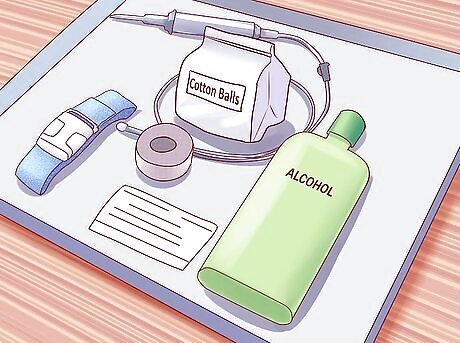

Gather your other supplies. These include a tourniquet (to help locate the vein you will insert the needle into), tape or medical adhesives (to keep all of the equipment in place once the needle is inserted), alcohol swabs (to sterilize the equipment), and labels (to keep track of the time of administration, the type of IV fluid, and the person who inserted the IV line). Always wear gloves for standard protection against blood and body fluid exposure.

Put all of your supplies on a tray. When the time comes to give the patient the IV, you will want to have all of your supplies right there. This will ensure that the procedure is done as quickly and easily as possible. You cannot stop in the middle of this procedure to go run for something you've forgotten.

Preparing the IV

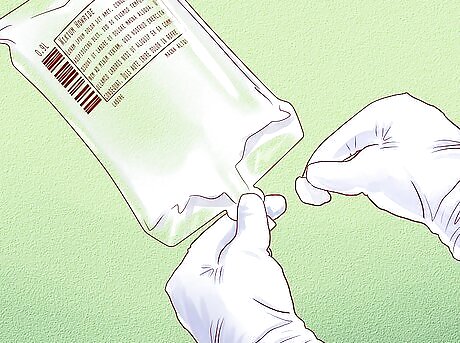

Prepare the IV bag. Locate the port of entry (this is located at the top of the IV bottle and is similar to a bottle cap). The port of entry is also where the macroset or microset line will be inserted. Unwrap an alcohol swab to sanitize the port of entry and the surrounding area of the bag. If you ever get confused while assembling the IV bag, there should be instructions written on the bag that you can follow. However, if you have any questions, stop what you're doing and find someone who knows what to do. Make sure the valve flow is set to "off" (you learn which way to move the slide on the tubing by experience). You want it set to stop the fluid from freely flowing until you've got the tubing inserted into the bag and the bag hung.

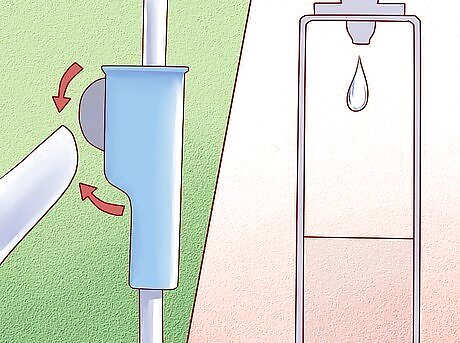

Pipe or insert the macroset or microset through the IV bag then hang it on the IV stand. Ensure that the drip chamber is in place (this is the part of the IV line that collects the fluid going through the patient’s vein). This is also the part where medical personnel are able to regulate the IV to make sure the patient gets the right medication. IV pumps, or infusion pumps, are often used to help deliver a precise dose for the proper amount of time.

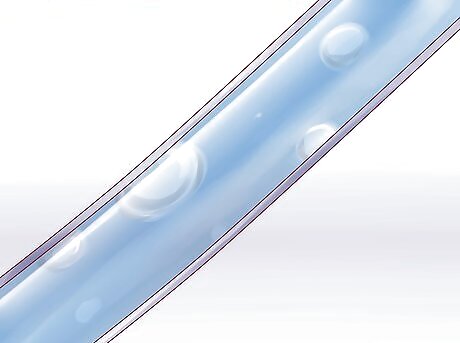

Hold the needle end of the tubing over the waste basket. Be careful that no part of the tubing touches the floor or any surface other than the patient's bed / mattress. Open the flow control--slowly--and let the fluid run through the tubing. Get rid of any air bubbles in the line. Make sure that the drip chamber is half filled. Once it is half filled, let the fluid in the IV flow until it reaches the end of the line (this is to remove any air bubbles are are trapped in the line). Close the flow control when the fluid reaches the end. To "close" you will use the control valve to clamp the tube. This is also termed as priming the IV tubing. This is an essential step, because inserting any air or air bubble into the patient could be fatal.

Make sure the line does not touch the floor. The floor could have bad bacteria on it, even if mopped each day. The IV is sterile (as in it does not have any bad microorganisms on it). If the line touches the floor, the fluid in the IV could be compromised (meaning bad microorganisms could get into it and infect the patient). If the IV line does touch the floor, you will have to prepare a new IV, as the contaminated IV could potentially harm your patient. Keep the IV line close so that it does not touch the floor again.

Giving the Patient the IV

Approach the patient. Be courteous, introduce yourself and tell him that you will be the one administering his IV fluids. It's best to lay all of the facts out for your patient — the needle puncturing his skin will hurt. It may sting, burn, or be uncomfortable for a short bit. Try to describe it so that he knows what he is getting into.

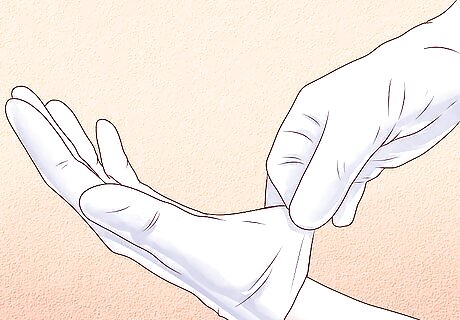

Position the patient. Ask the patient to sit or lie down on the medical bed or chair, whichever she prefers. Lying or sitting calms the patient and can reduce the amount of pain he will feel. It also ensures that she is in a stable position where she won't pass out if he has a psychological fear of needles. Wash your hands again to ensure extra cleanliness. Put on your gloves — this can also help reassure the patient that you care about her health and protecting her against unnecessary exposure to bacteria.

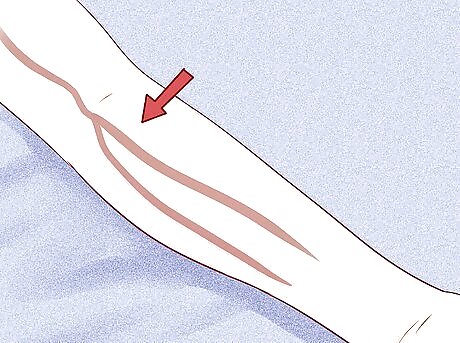

Look for the best place to insert the cannula. The cannula is the tube-like structure that you will insert at the same time as the needle, but the cannula stays in place after you take the needle out. You should look for a vein on the non-dominant arm (the one the person doesn't write with). You should look for a long, dark vein that you will easily be able to see when you are inserting the needle. Start by looking for veins lower down on the arm, or even on the back of the hand. Starting lower down will give you more "chances" if you are not successful at inserting the IV on your first try. If you need to try a second time, you will need to move higher up the arm, so there are benefits to trying lower down on the hand/wrist first if you can find a reasonably visible vein. Most hand or wrist veins look plump, but can roll. On heavier patients, it may be difficult to see or feel (palpate) hand or wrist veins. You can also look for veins that are located in the crease where the forearm meets the upper arm. This is called the antecubital space. These are often the easiest to insert an IV into; however, if the patient tries to bend his arm, this can block the IV tubing and the IV solution.

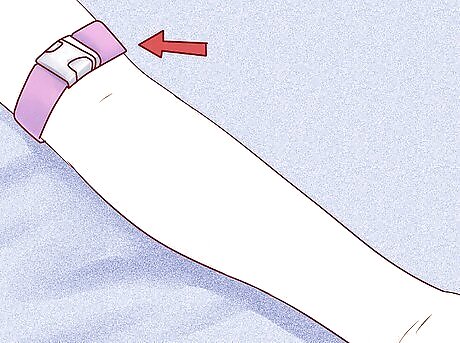

Tie the tourniquet directly above where you will be inserting the needle. For many patients, the tightness will be very uncomfortable. Offer reassurances. Tie it in a manner that will allow you to loosen it quickly. When you tie the tourniquet, it will cause the vein to bulge, which will make it easier to see the vein, and easier to insert the needle into that location.

Clean the spot where you will insert the cannula. Use an alcohol swab to clean the insertion site (the spot that you will be putting the needle into). Use a circular motion when you clean the spot so that you get rid of as many microorganisms as possible. Let the area dry. Still leave the tourniquet in place. Do not wave your hand over the area as if to dry it, as this can causes bacteria to be waved over the "cleaned area". Instead, allow the alcohol to air dry on its own. Note: Never, ever, blow air on the site using your mouth.

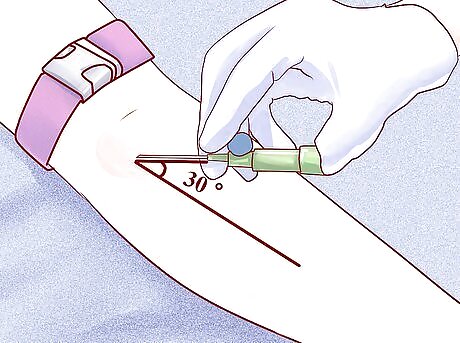

Insert the cannula. Position the cannula so that you are holding it at a 30–45 degree angle to the patient’s arm and vein. Hold the cannula like you would hold a syringe so that you do not accidentally pass it through the vein. When you feel a “pop” and dark blood appears inside the cannula, decrease the angle of insertion so it is parallel to the patient’s skin. If this is your first time you are attempting this procedure, make sure you are doing so under supervision. Push the cannula forward another 2mm. Then, fix the needle and push the rest of the cannula in a little bit further. Remove the needle fully. Apply pressure above insertion site while maintaining site and connect the IV tubing. If you do not apply pressure, the patient may bleed from the cannula. Once the tubing is connected, you still MUST hold the cannula in place until you get the site cleaned and taped. Dispose of the needle in a designated sharps container. Finally, untie the tourniquet and clean the insertion site where the cannula is sticking out of the skin with a hypoallergenic dressing or alcohol swab.

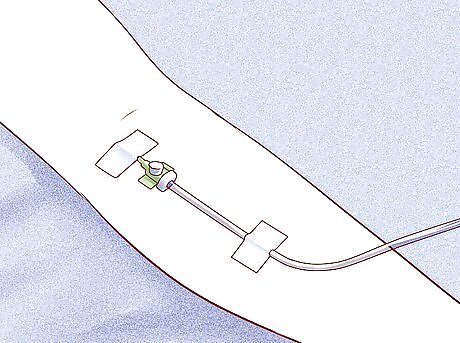

Connect the IV tubing to the cannula hub. You should do this by slowly feeding the tubing into the cannula until you can connect it. Make sure that it is secure once it is connected. Slowly open the line so that the IV fluid goes into the tube and into the patient. You should also put tape on the tubing so that it stays in place on the patient’s arm. Start by administering normal saline from a single needle/syringe in order to ensure the IV is open and unobstructed. If you notice swelling in the surrounding tissue (infiltration), or other problems with the fluid administration, stop the saline flush immediately. Immediately remove the cannula. You will need to start the process over again, but using a different insertion site. Assuming that the saline flows normally through the IV access point you have set up, you can proceed to administer any other medication(s) the doctor has specifically ordered to be delivered through the IV (e.g. IV piggyback).

Regulate the drops per minute. Regulate the IV drip rate according to the physician’s order. Usually in a clinic or hospital, the physician will order a specific rate, like millilitres per hour. In a field setting, you will need to regulate the IV rate manually. The IV may have roller clamps and you need to count the drops per minute as the drops fall into the chamber. Count the drips for a full minute, and adjust until you get the proper rate. Other IV sets already have a roller knob that you can turn and set the drops per minute so that you don’t have to count. IV machines in hospitals are easiest of course, because you set the drip rate using buttons, like setting a digital clock.

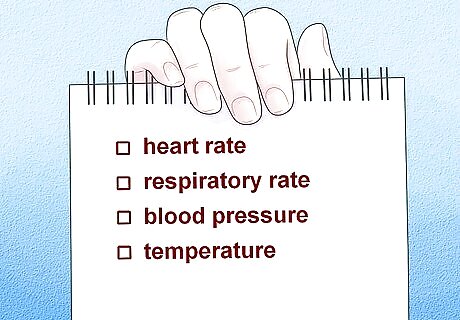

Monitor your patient for any signs of an adverse reaction. Check your patient’s heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure and temperature. Report any untoward signs and symptoms. These symptoms could include an elevated heart rate, increased respiratory rate, difficulty breathing, hives, anaphylactic shock, or an increase in temperature and raised blood pressure. A patient may also voice physical complaints or report feeling new symptoms. Always do an assessment of vital signs.

Comments

0 comment