views

Choosing a Type of Anti-hero

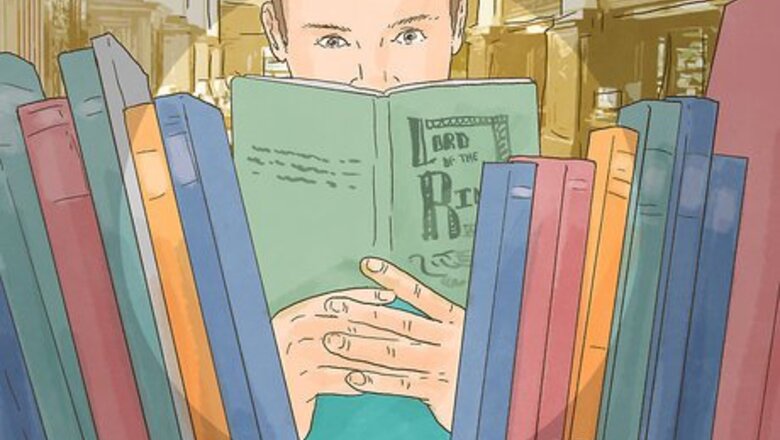

Use a classical anti-hero. This is the most common type of anti-hero, a character who doesn’t share the positive characteristics of a hero. This character can be filled with self-doubt, a poor fighter, cowardly, or dumb, all in contrast to a typical hero who is confident, capable, brave, and intelligent. This anti-hero may spend the story overcoming his or her weaknesses to become more heroic, even if he or she just succumbs to them in the end. Frodo Baggins from “The Hobbit” is a good example, as he shows a lack of self-confidence and fighting ability, only to grow into a more heroic figure by the end of the story. Another example might be the title character from the novel “Don Quixote,” who is likely senile and suffers from delusions of grandeur as he attempts to live out the chivalric tradition.

Use a Disney anti-hero. These are anti-heroes with a heart of gold. The anti-hero will have some flaw or internal conflict that he or she must overcome in the story arc to become a regular hero by the end of the narrative, usually leading to a happier ending. The anti-hero probably knows the good or “heroic” way of doing things, but needs to be given a reason to do so. Though not a Disney creation, Shrek the Ogre fits this template as even though he is crude and cynical, he does end up doing the right thing for characters he cares about.

Create a pragmatic anti-hero. These are characters who are willing to do what is necessary to accomplish their goals. The pragmatic anti-hero is darker than a Disney anti-hero, and not guaranteed to become a more regular hero. For this character, the end usually justifies the means, usually explained by saying “I did what I had to do,” or “whatever it takes.” Popular examples of this type are police or security officials willing to cross the line when necessary to solve the crime, such as Dirty Harry and Jack Bauer.

Make an unscrupulous hero. This is similar to the Pragmatic Anti-Hero in that he or she has good intentions, but far fewer restrictions on their actions. The important thing is that whatever bad things you can say about what the anti-hero does, their enemies are always worse. These kinds of characters work best in darker settings, so this is probably better for works targeting a more mature audience. Captain Jack Sparrow from the “Pirates of the Caribbean” series is a good example, as he is willing to lie, cheat, and steal from other characters to ensure his own success, or survival, or both.

Make a nominal hero. These anti-heroes fight on the good side, but do so for bad reasons or intentions. The important part of the story is that he or she has a reason to dislike the villain, making the anti-hero a useful ally. These reasons are usually personal, and if the anti-hero is a side character, they may depart partway through the story once this desire is fulfilled. Eric Cartman from the show “South Park” can be a good example of this when he works with the other characters. While their intentions may be noble, Cartman is usually attached only for his own personal gain.

Mix anti-hero types. You’ll notice that while there are many different types of anti-heroes, your anti-hero may fit into several categories at once. That is fine as these are meant to be guidelines that help explain both what type of person your anti-hero is, and where they fit into the storyline. Your anti-hero may fall mostly in one category, but also exhibit characteristics of another.

Defining Your Anti-Hero

Define your anti-hero’s flaw. A good anti-hero has something that makes him or her hard to put up as a great example to others. An anti-hero will not exhibit all the traits that society considers admirable, and will probably reject some of them explicitly. Anti-heroes can lie, cheat, steal, act cowardly, and even kill as part of accomplishing their goals. Your anti-hero doesn’t need to do all of these things, but must have some flaw that prevents him or her from being a true hero, at least when your story begins. Your anti-hero’s flaws will influence the role he or she plays in your story. Shakespeare’s Hamlet is a good example, as while he wants to avenge his father’s death, he is consumed with self-doubt and hesitation, which prevents him from acting throughout much of the play. Dr. Gregory House, though a brilliant physician, abuses drugs and mistreats his friends and co-workers throughout the series.

Decide if your anti-hero is the protagonist. A good anti-hero doesn’t necessarily need to be the main character, but instead a sidekick or helper to the main hero. If your anti-hero is the main character, their emotional arc, decision-making, and internal struggle will become a central feature of the story. A good anti-hero sidekick can add some color to your story, and help provide the moral choices your hero needs to accept in order to achieve the ultimate goal. Han Solo is a helpful sidekick to the main character, Luke Skywalker, during “Star Wars: A New Hope,” providing assistance throughout the story while complaining about getting his financial reward.

Create some limits for your anti-hero. One big difference between an anti-hero and a villain can be that the anti-hero has some limit to their bad actions, some things he or she just won’t do. This is important, as without limits, your audience won’t find the anti-hero sympathetic. Not hurting children or pets is a good one, or maybe your anti-hero writes a letter to their mother every week. Explaining this limit can be a good way to help flesh out your anti-hero’s backstory. The Godfather, Vito Corleone, orders others killed or threatened as part of his leadership of the crime family, but draws the line at selling drugs until he is forced to by the other families. He is also willing to use his influence to help friends and family members. Even his son Michael, the main character in the three movies, waits to have his brother Fredo killed until after their mother dies (so she doesn’t have to know about it).

Think about your audience. Consider who you expect to watch/read your story, and why your anti-hero would appeal to them. Look for things they consider to be negatives, flaws that would make your character an anti-hero, but also what limits they might expect an anti-hero not to cross. Remember that different audiences, including genders and age groups, will find different kinds of anti-heroes compelling. Many anti-heroes in modern television series are middle-aged, reflecting a large portion of the audience who watches those shows. While most people are not mobsters like Tony Soprano or womanizing ad men like Don Draper, they can recognize the fear of reaching that part of their lives, balancing work, family, and personal concerns, and struggling as the world changes around them.

Putting Your Anti-Hero into Action

Explain your anti-hero’s backstory. Make sure your audience knows why the anti-hero acts the way he or she does. By providing an explanation, your audience will be able to justify liking, or at least not hating, the anti-hero character. Maybe your anti-hero has a tragic past, something that makes them act the way they do. Giving your anti-hero a reason for their actions can generate sympathy from your audience, and forces them to think how they would respond in those circumstances. Severus Snape, for example, expressed a dislike of Harry Potter because the character’s father bullied him when they were in school. If you want to add some drama to the story, you can make the anti-hero’s backstory a mystery, something for other characters to discover or reveal.

Make sure your anti-hero is good at something useful. Even if your anti-hero is a despicable character, he or she needs to have some skill that makes them useful to the story or otherwise gives them a reason to stick around. It will be easier for your audience to accept your anti-hero’s flaws as long as the character serves some purpose. The TV doctor House, for example, is difficult and unpleasant with other characters, and tries to solve medical mysteries not to help people, but satisfy his own ego. He is also excellent at solving those mysteries, meaning other characters put up with his flaws, and even want him around.

Give your anti-hero a noble purpose. If nothing else, there needs to be a good thing your anti-hero is working toward. As long as the end result is good, your audience will probably forgive a lot of otherwise negative actions. The main character is the series “Dexter” is a serial killer, but one who only targets other serial killers. Though his actions are brutal, he is doing them to rid the world of other dangerous people.

Create a chance at redemption. Your anti-hero doesn’t need to become a full-fledged hero by the end of the story, but he or she should be presented with a chance to reject his or her flaws for something greater. An anti-hero choosing between good and evil is generally more believable. Your audience can better see the internal struggle such a decision will create for a flawed character rather than a more idealized hero. In Dostoevsky’s novel “Crime and Punishment,” the main character Raskolnikov eventually confesses to killing two people. He will gain redemption, but only after serving the psychological punishment of his own guilt, and spending time in prison. As an anti-hero, your character can always believably reject the heroic choice and become a villain, which won’t seem terribly out of place, especially if they are an Unscrupulous or Nominal Hero.

Comments

0 comment