views

Starting With Your Audience

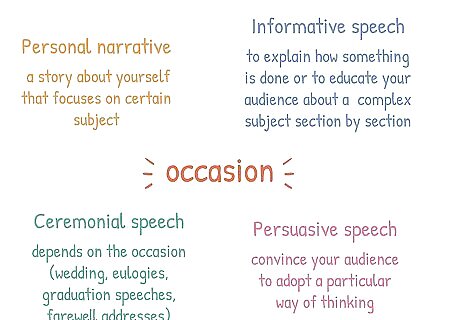

Be clear on the occasion. It's important to know what kind of speech you're giving and why your audience is gathering to hear it in order to get started on the right foot. Understand if your speech is meant to be a personal narrative, informative, persuasive or ceremonial. Personal narrative. A narrative is just another word for story. If you're asked to tell a story about yourself, find out if the intention is to use something that's happened to you in order to teach a lesson, convey a moral, offer inspiration or simply to entertain. Informative speech. There are two kinds of informative speeches: process and expository. If you're charged with doing a process speech, the idea is for you to explain how something is done, how something is made or how something works. You take your audience step-by-step through the process. If your speech is meant to be expository, your job is to take what might be a complex subject and break it down into sections as a way of educating your audience about the topic. Persuasive speech. If you're meant to persuade, then your job is to convince your audience to adopt a particular way of thinking, a belief or a behavior that you advocate for. Ceremonial speech. Ceremonial speeches run the gamut from wedding toasts to eulogies, from graduation speeches to farewell addresses. Many of these speeches are intended to be short and the focus is often on entertaining, inspiring or increasing the audience's appreciation for someone or something.

Pick a topic that will interest your audience. If you have the option, choose to speak about something that your audience will find interesting or enjoyable. Sometimes, you don't have a choice about your topic--you find yourself assigned to speak about something in particular. In that case, you must look for ways to keep your audience engaged in what you have to say.

Set a goal. Write a one-sentence statement about what you want to accomplish on behalf of your audience. It could be something as simple as "I want my audience to learn the four things they should look for when buying a diamond" or "I want to convince my audience to give up fast food for a month." It may sound simplistic, but writing down this kind of goal statement does two thing: it helps keep you on track as you begin putting your speech together, and it helps remind you to keep your focus on your audience as you move through your speech preparation process.

Always keep your audience in mind. It would be a terrible waste of time and effort if you devoted yourself to putting a speech together and the audience tuned out or couldn't remember a word you said by the time you were done. You continually want to think of ways to make what you have to say interesting, helpful, relevant and memorable to your audience. Read the newspaper. If you can find a way to link your speech topic to something that's happening in the news, you can highlight the relevance of what you have to say to your audience. Translate numbers. Using statistics in your speech can be impactful, but they can be even more meaningful if you translate them in a way the audience can understand. For example, you could say that worldwide, 7.6 million people die of cancer every year, but to make it more relatable, you might want to follow it up by saying that that number represents the entire population of Switzerland. Express the benefits. It's a good idea to let an audience know exactly what they'll get out of your speech, so that they're primed to listen. If they'll learn how to save money, tell them. If the information you're about to share will make their lives easier in some way, make that clear. If they'll gain a new appreciation of someone or something, let them know.

Researching and Writing Your Speech

Know your subject. In some cases, you might need to do nothing more than sit down, gather your thoughts and put all of your ideas on paper. Other times, your topic will be unfamiliar enough that you must do research in order to speak about it knowledgeably. Most times, you'll fall somewhere in between the two extremes.

Do broad research. The internet can be a great source to find out more about your speech topic, but don't necessarily stop there. If you're a student, use your school's library or library databases. Many public libraries subscribe to databases that house thousands and thousands of articles. If you have a library card, you have free access to those databases. Think about interviewing someone who's an expert in your topic or conducting a survey. The more ways you go at gathering the information you need, the more successful you're likely to be. Plus, using various research sources gives your speech breadth.

Avoid plagiarism. When you do use information you got from an outside source in your speech, plan to give credit to that source. To do so, keep track of where you're getting your information so that you can cite it later on.

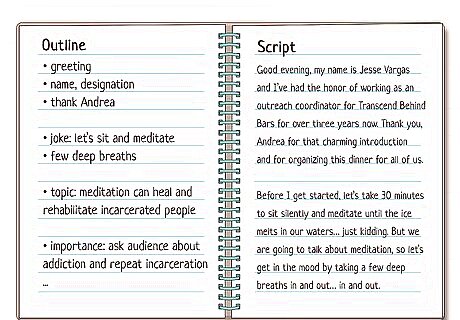

Decide if you'll outline or script. Narrative, informative and persuasive speeches lend themselves well to being outlined while ceremonial speeches are best written out. Outline. When you outline, you're simply organizing and structuring your speech as a series of points. For example, if you were giving the speech mentioned above: "I want my audience to learn the four things they should look for when buying a diamond," you might designate one point for "Cut," one for "Color," one for "Clarity" and one for "Carat." Under each of those points, you'd offer your audience more information and detail. Outlines can be written in complete sentences or they can be a series of abbreviated phrases and reminders. Another approach is to begin by writing complete sentences and then transferring your outline on to note cards on which you abbreviate those sentences using just the words and memory prompts you need. Script. One reason that it makes sense to write out ceremonial speeches is because the words you choose to express yourself in these kinds of speeches are particularly important. You're meant to inspire or entertain or pay tribute to someone, so saying exactly what you mean and have prepared increases your chances for success. Pull out your old English textbooks and review things like similes, metaphors, alliteration and other kinds of figurative language. These kinds of devices can add to the impact of a ceremonial speech. Beware one pitfall of the scripted speech: having a page full of words in front of you can cause you to fall into the trap of simply reading from your script without every looking up, making eye contact or engaging with the audience in any way. Thorough practice should help to eliminate your chances of falling into this trip.

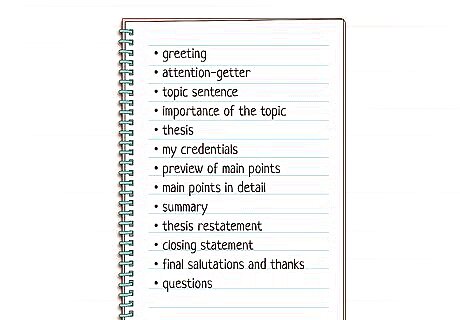

Be sure you have all the pieces in place. A speech includes three basic pieces: an introduction, a body and a conclusion. Be sure your speech contains all of these elements. Introduction. There are two things that most good introductions include: an attention-getter and a preview of what's to come in the speech. Give an attention-getter. The most important thing you must do in your introduction is to grab your audience's attention. You can do this in a number of ways: ask a question, say something surprising, offer startling statistics, use a quote or proverb related to your speech topic or tell a short story. Take the time to figure out how you'll grab your audience's attention--it's easier to get them hooked in the beginning than to try to get them interested as your speech progresses. Offer a preview. Think of a preview as kind of the "coming attractions" of your speech. Plan to tell your audience the main points you'll talk about in your speech. There's not need to go into any detail here; you'll get to that when you come to the body of your speech. You can write a preview that's simply one sentence in length to cover what you need to say here. Body. The body is where the "meat" of your speech resides. The points you outlined or the information you scripted make up the body. There are several ways to organize the information within the body of your speech--in time sequence, in step order, from most important point to least important point, problem-solution, to name just a few. Choose an organizational pattern that makes sense based on your speech goal. Conclusion. There are two things to accomplish in your conclusion. This is not the place to introduce any new information; instead, the idea is to wrap things up in a way that's memorable and definite. Give a summary. One of the ways an audience remembers what a speech was about is through intentional repetition. In your introduction, you gave a preview of what you'd be talking about. In your speech body, you talked about those things. Now, in your conclusion, you remind your audience what you talked about. Simply offer a brief review of the main points you touched on in your speech. End with a clincher. A clincher is a memorable, definitive statement that gives your speech a sense of closure. One easy way to do this is to write a clincher that refers back to what you said in the attention-getter of your speech. This helps bring your presentation full circle and provides a sense of closure.

Choosing Visual Aids

Choose visuals to benefit the audience. There are many good reasons to use visual aids. They can help make things easier to understand, they help audiences remember what you've said, they appeal to visual learners, and they can help an audience view you as more persuasive. Be sure you're clear on what you hope to accomplish with each visual you incorporate into your speech.

Pick visuals that suit the speech. While it's a great idea to use visual aids in your speech, be sure to choose ones that make sense. For example, in the speech mentioned above in which the speaker wants the audience to learn the four things to look for when buying a diamond, it might would make sense to show a diagram of a diamond that illustrates where a jeweler makes cuts in preparing the gemstone. It would also be helpful to show side-by-side photos of clear, white and yellow diamonds so the audience can recognize the differences in color. On the other hand, it wouldn't be very helpful to show an exterior photo of a jewelry store.

Use PowerPoint with care. PowerPoint can be a great delivery device for visual aids. You can use it to show photos, charts, and graphs with ease. But there are common mistakes that speakers sometimes make when using PowerPoint. These are easy to avoid once you stop and think about them. Don't write everything you plan to say on your slides. We've all suffered through speeches where the speaker did little more that read off of his or her slides. That's boring for the audience, and they soon disengage. Instead, use word charts to preview, review or highlight key information. Remember, the sides should be a supplement to what you're going to say rather than an exact copy of it. Make your slides readable. Use a font size that's easy for your audience to read and don't overcrowd your slides. If your audience can't see or get through the material on your slides, they won't have served any purpose. Use animations sparingly. Having graphics fly around, zoom in and out ,and change colors can be engaging but can also be distracting. Be careful not to overdo the special effects. Your slides should be a supporting player rather than the star of the show.

Rehearsing Your Speech

Give yourself plenty of time. The more time you have to practice your speech, the more prepared you'll feel, and as a result, the less nervous you'll feel. One guideline for the amount of time to spend on preparing a speech is one to two hours for every minute you'll be speaking. For example, you might want to devote 5 to 10 hours of prep time for a 5-minute speech. Of course, that includes ALL of your preparation from start to finish; your rehearsal would be just a portion of that time. Leave yourself time to practice. If you're given to procrastinating, you could find yourself with very little or no time to practice before you deliver your speech, which could leave you feeling unprepared and anxious.

Practice in front of people. Whenever possible, give your speech in front of family members and friends. If you want their feedback, give them specific guidelines for what you'd like them to comment on so that you don't feel overwhelmed by helpful notes. Look at your audience. Almost nothing does more to keep an audience engaged than eye contact from a speaker. As you rehearse your speech, be sure to look at the family members or friends who've agreed to be your audience. It takes a bit of practice to be able to look at your outline, script or note cards, capture a thought or two and then come up and deliver that information while looking at your audience. It's yet another reason why rehearsal time is so important. If you don't have the opportunity to practice in front of people, be sure that when you do rehearse, that you say your speech aloud. You don't want your speech day to be the first time you hear the words of your speech coming out of your mouth. Plus, speaking out loud gives you a chance to double-check and correct any mispronunciations, practice articulating your words clearly and confirm the timing of your speech (We speak more quickly when we simply recite a speech in our heads).

Be OK with changes. One thing rehearing your speech allows you to do is to make any necessary changes. If it's running too long, you have to cut some material. If it's too short or some sections seem skimpy, you add more. Not only that, but each time you practice your speech aloud, it will come out a bit differently. That's perfectly fine. You're not a robot, you're a person. It's not necessary to get your speech word-for-word perfect, what matters is conveying the information in an engaging and memorable way.

Reducing Speech Anxiety

Get physical. It's common for people to feel physical symptoms of nervousness--rapidly beating heart, quick breathing and shaky hands--before giving a speech. That's a perfectly normal response caused by a release of adrenaline in the body--something that happens when we feel threatened. The key is to engage in physical activity to help move the adrenaline through your system and allow it to dissipate. Clench and release. Ball up your fists really, really tight and hold for a second or two and then release. Repeat this a few times. You can do the same thing by squeezing the muscles in your calves very tightly and then releasing. With each release, you should feel a reduction in your adrenaline-induced symptoms. Take deep breaths. The adrenaline in your system causes you to take more shallow breaths that, in turn, increase your feeling of anxiety. You need to break the cycle. Take a deep breath through your nose and allow the air to fill your belly. Once your belly is full, let your breath fill and expand your ribcage. Finally, allow your breath to move fully into your chest. Open your mouth slightly and begin to exhale starting first with the air in your chest, then the air in your ribcage and finally the breath in your belly. Repeat this inhale-exhale cycle five times.

Focus on your audience. While it might seem difficult to believe, a good speech is really not about you, the speaker. It's about the audience. Plan to put your total focus and concentration on your audience throughout your speech, especially in the beginning. Really take them in and check out the non-verbal messages they're sending you--do they understand what you're saying? do you need to slow down? are they in agreement with you? would they be open to you moving closer to make a stronger connection? If you put your attention fully on your audience, you won't have time to think about your own nerves or anxiety.

Use visual aids. You're probably planning to use visual aids anyway, but if you're not, you might want to consider it. For some people, using visual aids reduces their anxiety because it makes them feel less like the center of attention; instead, they feel as though they're sharing the spotlight with the visuals.

Practice visualization. When you use visualization you simply create a mental image of you successfully giving your speech. Close your eyes and see yourself sitting down prior to your speech. Hear your name being called or your introduction being given. Visualize yourself standing up confidently, picking up your notes and walking to the podium. See yourself taking a moment to make sure your notes are in order and looking up to make eye contact with the audience. Then picture yourself giving your speech. Watch yourself move through the entire talk successfully. See the speech end, yourself saying "thank you" and returning confidently to your seat.

Stay positive. Even if you're feeling nervous, do your best not to engage in a lot of negative talk. Instead of saying "This speech is going to be a disaster" say instead "I did the best I could preparing this speech." Replace "I'm a nervous wreck" with "I feel nervous, but I know that's normal before a speech, and I won't let that stop me from doing my best." Negative thoughts are incredibly powerful--one estimate is that you need five positive thoughts to counteract every one negative thought you have, so steer clear of them.

Comments

0 comment