views

- Understand that isolation is a common symptom of PTSD. Try not to take it personally, and give your loved one time and space if they need it.

- Let them know you're there for them if they want to talk, and try to maintain a calm and relaxing environment.

- Discuss their triggers with them so that you can both develop a game plan for handling triggers when they arise.

- Take care of yourself, and don't put your life on hold for your loved one. Their well-being is important, but it doesn't take precedence over yours.

What You Can Do When You’re Pushed Away

Remind yourself that their trauma isn’t about you. Your loved one is struggling with powerful anxiety and fear, and though you will almost certainly feel the effects, they likely can’t control it. Try not to feel hurt when they suddenly withdraw from you: it’s not anything you’ve done, and it’s not a reflection of how they feel about you. Your loved one is stuck in a state of constant vulnerability and high alert which might make them irritable, depressed, anxious, and mistrustful. Don’t take it personally—but also don’t feel pressure to “fix” them or their symptoms. You can support them without taking on responsibility for their emotions or actions.

Voice your support without pushing them. When your loved one isolates, they may just need some time alone, or they may need a shoulder to lean on. Voice your presence and support, but don’t push them to come out of their shell sooner than they’re ready to. They may not know what they need in the moment, but it’s important that you give them the agency to decide. You can show support in a variety of ways. You can make them tea or dinner, or just communicate that you’re there and that there’s no rush for them to feel better. Sometimes, all a person needs is to know that they won’t be forgotten or abandoned while they work through their difficult emotions. Knowing you’ll be there when they emerge may even make them feel better sooner.

Offer a listening ear. Your loved one may not want to talk about their experiences—or they may want to talk a lot! Let them know you’re there to listen, but don’t pressure them to open up to you about their trauma if they don’t want to. Even if they don’t end up wanting to talk, they may feel calmer knowing you’re there and that you care. What to Do: Let them take the lead, and practice active listening: nod, maintain eye contact, and respond and ask questions that indicate engagement and offer validation: “That must have been really hard,” “When did that happen?” “I’m glad you’re telling me all this.” Keep the focus on them and on how they feel, rather than what you feel about their experience. You’ll probably feel a lot of things—but this conversation isn’t about you. What Not to Do: Avoid empty platitudes that may come across as dismissive, like “Everything will be OK,” “There’s a reason for everything,” or that they’re “lucky” things weren’t worse. Some of what they say may be very hard to listen to, especially if they suffered or inflicted violence. Try to avoid showing judgment or horror, as this may discourage them from opening up to you again.

Use nonjudgmental language. When you show support of your loved one or talk to them about their trauma, use respectful, gentle, and nonjudgmental language. Try to avoid giving unsolicited advice or telling them what they “should” do. Let them know you’re there for them, you see that they’re suffering, and you want them to know they’re not alone. Keep in mind that you aren’t in control of what they need, and what they want to do may not align with what you want them to do. “If you want to talk, I’m here to listen, but I understand if you don’t feel comfortable opening up to me. I’ll check in with you later, but there’s no pressure to talk if you don’t want to.” “I can tell you’re suffering a lot right now. Would you like me to stay with you? I’m here if you want to talk, but I’m also happy to sit quietly with you if that’s what you need.” “You’ve struggled a lot. I love you so much, and I’m so glad you’re here. Let me know if I can do anything to support you.” “I know you want to be alone when you're upset. And that’s OK. I love you, and I’ll do what I can to support you through the hard moments. Take as much time and space as you need.”

Work to rebuild trust and safety. Your loved one is struggling to feel safe and secure, and while you can’t erase their trauma, you can help them to feel more comfortable and rebuild their trust. Let them know you’re committed to your relationship and to supporting them through the difficult times. Establish routines with your loved one, like regular walks or nightly tea and conversation, or cooking dinner together. Structure can help restore a feeling of stability and safety. Talk about the future with them. Make plans, and keep your promises. Minimize stress around them. If you live together, try to keep your home life calm and relaxing. Encourage and empower them by acknowledging their strengths and reminding them of all their successes. This will help to reestablish their self-trust and self-confidence.

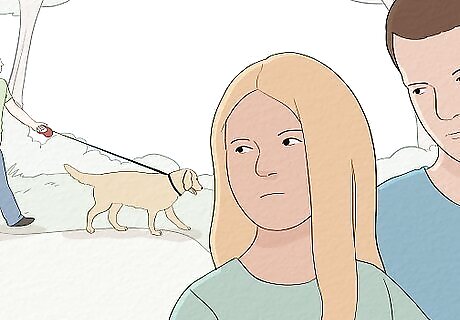

Stay alert to likely triggers. PTSD can be triggered by reminders of the traumatic event. For instance, if your loved one was in combat, seeing their veteran friends may be hard for them, or being in crowds may make them feel on high alert. Triggers may be internal (happening inside the body) or external (happening outside the body). Being aware of what might trigger your loved one can help you and them to manage their reactions. Some triggers may be avoided, but many just need to be managed and planned for. Ask your loved one what has helped them deal with a trigger in the past, and develop a game plan with them to respond to triggers when they arise in the future.

Keep doing “normal” things with them. One of the hardest parts of experiencing trauma is returning to “normal” life. Doing everyday activities with your loved one and talking about everyday things will help ground them and make them feel connected to “normal” life again. It may also offer a welcome distraction from their symptoms. Your loved one struggles with PTSD, but PTSD doesn’t define them. Invite them to parties or to dinner, ask them to watch a new TV show with you, talk about “normal” things, like the weather or your day. This will not only help ground them in reality or distract them from their symptoms; it may reassure them you don’t view them as “different.”

Be patient. Watching your loved one suffer is hard. Feeling they’re withdrawing from you is hard too. But try to be patient and remain calm. Give them the space and time to heal in what way works best for them. Voice your support, but in the meantime, keep doing your thing. When your loved one is struggling, you might feel pressure to help, or their anxiety may make you anxious or irritable yourself. Try to remain calm and take their PTSD symptoms in stride. You may feel helpless, or as if just sitting and waiting isn’t doing any good. But your loved one may be encouraged to know there’s no pressure for them to heal faster.

Practice good self-care. Supporting someone struggling with PTSD can drain you if you don’t take good care of yourself and *establish appropriate boundaries. Remember that you’re not responsible for your loved one’s recovery, and that in order to offer them the best support, you need to take frequent breaks and bring in outside help as needed, and don’t put your life on hold for them. Get good self care by getting plenty of exercise, eating well, and taking time to pursue your own interests. This will help you maintain independence and avoid slipping into a codependent relationship with your loved one. Supporting someone with PTSD can in turn affect your own mental health. If you feel drained, or even traumatized yourself by what your loved one has been through, try confiding in a therapist or a trusted friend or family member. Remember, your loved one’s well-being doesn’t take precedence over your own. Taking care of yourself may mean encouraging them to get additional support elsewhere. You can do a lot to support your loved one in their time of need, but they may also benefit from outside help, such as medication, therapy, or a support group.

Why Someone with PTSD Might Push You Away

They may push you away because their PTSD symptoms were triggered. PTSD lives in the body, meaning the symptoms can be very physical and visceral, but triggers may be internal (inside the body) or external (outside the body). Certain things may remind your loved one of the traumatic event they experienced, and your loved one may feel as if they are experiencing the event again. Common external triggers include news coverage about events related to their trauma; sights, sounds, or smells associated with their trauma; anniversaries or certain times of day; nature, such as certain types of weather; people and places related to their trauma; situations that feel claustrophobic, such as crowded spaces; relationship, school, work, or other pressures; funerals, hospitals, or medical treatment. Common internal triggers include physical discomfort like hunger, exhaustion, fatigue, sickness, or sexual frustration, or reminders of bodily trauma such as scars or pain; overwhelming emotions, like helplessness or feeling trapped; feelings for loved ones, including love, resentment, or anxiety.

Isolation may be a form of self-preservation for your loved one. The trauma they experienced threatened their safety, and perhaps even their life. When triggered, someone with PTSD may enter fight-or-flight mode, and as a result, they may withdraw from others. Even when they aren’t triggered, a person with PTSD may be generally withdrawn from a desire not to exacerbate their symptoms. When triggered, many people with PTSD experience anxiety and paranoia, and struggle not to be on high alert. Even if they “know” they are safe, it can feel easier to withdraw from other people or places. Being triggered can be exhausting. But if you knew your loved one prior to their trauma, you may notice they are generally more withdrawn than they used to be. This could be because they feel generally more anxious and less safe in the world.

They may not feel in control of their emotions. People with PTSD can struggle with extreme emotions, including grief and shame, which often masquerade as rage. If your loved one withdraws from you, it could be that they aren’t yet comfortable exposing certain emotions to you. Perhaps they think you won’t understand, they’re not sure if they can trust you fully, or they worry their anger will cause them to act in ways they’ll later regret. Many people who suffer a traumatic event struggle to reintegrate into the “real world.” Your loved one likely feels not just unsafe, but alone. And feeling alone may make them think they should be alone. They may struggle with anger—misguided anger at themselves for “letting” their trauma happen, or anger at anyone who may have caused the trauma. They may withdraw if they feel their anger could cause them to become violent or to say hurtful things. Anger is also a common response to love. While your loved one needs your support and acceptance, low self-esteem may make them feel unworthy of your love, or it may stir vulnerable feelings in them that they would rather not deal with.

Getting Outside Help

Therapy can help people with PTSD overcome their trauma. If your loved one doesn’t already see a therapist or psychiatrist, it may be beneficial to their healing. Many people who have undergone trauma are understandably reluctant to talk about it, but talking about trauma with a trained therapist and, if necessary, taking medication can help your loved one learn to manage their symptoms. Though talking about trauma is hard, it can also lessen the trauma’s power over time. In therapy, your loved one may learn to become more comfortable with their trauma, even to the point of getting “bored” of it. Therapy isn’t only beneficial to your loved one; it may also help diffuse any pressure you feel to be their caretaker. Your loved one may rely on you a great deal, but if they are only relying on you, that’s a problem.

It may benefit them to connect with people who can relate. Your loved one may be struggling with something they don’t feel they can talk to you about. Try not to take it personally if this is the case, and encourage them to reach out to others who may be able to relate for support—such as friends who may have undergone similar experiences, or group therapy. For instance, if they’re a combat veteran and you’re not, they may not feel they can fully open up to you. Encourage them to reach out to people they knew in combat, if they don’t already. Be aware that while talking about their trauma can help your loved one feel more understood, it can also trigger some PTSD symptoms temporarily.

What is PTSD?

PTSD is a mental health condition triggered by a frightening event. It stands for post-traumatic stress disorder, and those who suffer from it may have experienced the traumatic event themselves, or only witnessed it. People with PTSD may struggle with nightmares and flashbacks about the event, extreme anxiety or depression, and uncontrollable thoughts about what happened. Common sources of PTSD include combat exposure, childhood physical abuse, sexual violence, physical assault, being threatened with a weapon, or an accident. To meet the criteria for PTSD, symptoms must last longer than a month and interfere with the person’s daily activities. Symptoms usually begin within 3 months, but they may not appear for years.

PTSD is caused by trauma, but not all trauma causes PTSD. Mental health professionals distinguish between little-t trauma and big-T trauma, with big-T trauma referring to an intensely frightening or life-threatening experience and little-t trauma referring to an experience that is emotionally disruptive, but not necessarily life-threatening or intense. Little-t trauma usually doesn't lead to PTSD, but it can, especially if the trauma occurs frequently and accumulates. Someone who suffered sexual assault, experienced military combat, or was in a serious car accident might have big-T trauma. Not everyone who experiences big-T trauma will go on to develop PTSD, and PTSD doesn't always last forever. Some people experience temporary mental health issues and eventually heal from it. Examples of little-t trauma include a divorce, getting fired, or moving to a new place. These events aren't life-threatening, but they can be unexpected and leave you feeling extremely ungrounded. While single little-t traumatic events may not lead to PTSD (though they can), if a person experiences little-t trauma over a long period of time, such as a child growing up in an emotionally abusive home or being bullied in school, they may experience symptoms of PTSD.

Comments

0 comment