views

It is 7:30 in the morning and we are standing in the middle of a huge ground in Lelhari village of South Kashmir’s Pulwama. We have come to attend a militant funeral. And it has begun, like a crushed leather bag, taking shape, slowly, reminding you of a life that once was.

A dozen or so people are checking arrangements. Loudspeakers are being tested. Banners have been put up and at one of the corners of the field a tractor has been placed. On it is the body of a dead militant who was killed the previous day.

Meanwhile people come and start taking their places without any guidance. The discipline with which rows and rows of men and women, who sit separately, are added one after the other is both an astounding and a depressing sight.

A participant says that the village has hosted funerals of over 14 militants, all locals of Lelhari, in the past two months. “So we all know by now what to do.”

The emcee of the ceremony, a fierce looking man, keeps scolding youth chatting behind the stage, embarrassing them individually, “Abid, have you come to a party? Younus have you come here to greet your friends?” Abid, Younus and the rest disperse immediately.

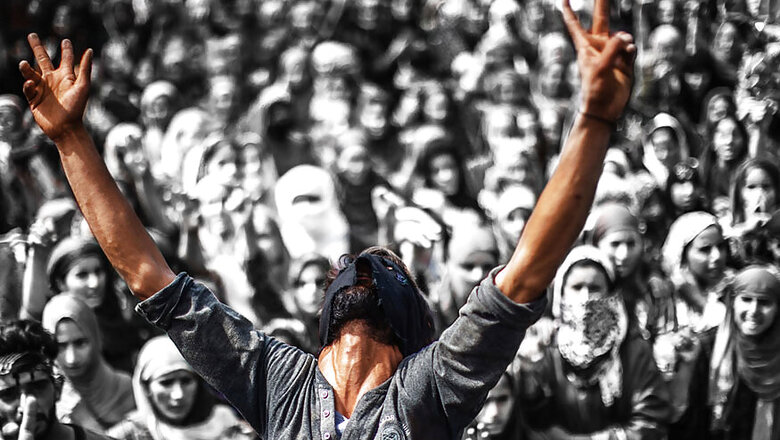

It is the women, who turn up in hundreds, that the organisers have a real difficulty in controlling. Women, like young boys with video camera phones and journalists, weren’t allowed at militant funerals. They struggled to create their own space and have now become essential to these events.

Women shouting slogans at the funeral of Ayyub Lelhari of Lashkar-e-Toiba. Ayyub,a district commander of LeT, was killed in an encounter with security forces on August 16, 2017.

The women, more than men, try getting near the stage, where Ayyub Lelhari’s body has been draped in a Pakistani flag, to get a better view and are repeatedly told to back-off. They go back and, independently of whatever is happening on the makeshift stage, you hear them shout their own slogans.

The flag in which a dead militant is wrapped is another story.

Just 14 days before Ayyub, funeral prayers were held here for another Lelhari boy, Arif Nabi Dar or Arif Lelhari. He was wrapped in a black, Tawheed flag, like several other militants are nowadays.

Flag battles, between Zakir Musa supporters who shout his name during funerals and wrap militants in black flags, and traditional Lashkar-e-Taiba and Hizbul Mujahideen cadres, whose loyalties are still with Pakistan, are regular now at militant funerals in Kashmir. Zakir Musa’s black flag supporters often get beaten up in process. But that doesn’t deter them from trying on.

“It is mostly an attempt to get noticed, that’s all. You had black-flag wavers in downtown Srinagar covered by TV channels and now you have militants wrapped in black flags given more airtime, which encourages them more,” says Shehriyar, an independent photojournalist who has covered militant funerals in Kashmir for last three years.

A lot of children turn up for the funeral as well. Two of them we spoke to, said they didn’t know Ayyub. Then why had they come? “I know Burhan. Ayyub was mujahid. Army killed him.” Before the conversation could move ahead, their mothers angrily asked them to return.

'In time, speaker after speaker, go on to lash themselves and their audience, breathe fire and call on the forefathers’ sacrifices. The crowd, as it swells dissolving private fears and embarrassment, responds with resounding chorus.'

Beside the body of Lelhari, one spots a poster of Burhan. It seems surprising that photo of a Hizbul Mujahideen commander should be placed at a funeral of a Lashkar militant, till a villager explains, “We don’t have time nor the means to publish new posters every time. We put up whatever we have.”

It is about 8:30 now. The sun has come out as have hundreds of people. A spokesperson for a Hurriyat group comes on stage and starts shouting slogans in praise of SAS Geelani. The crowd responds feebly, and only after much prodding from the speaker.

Funerals are an opportunity that several factions of separatists, in this case the SAS Geelani faction — the Hurriyat (G), use to promote and keep themselves relevant when passions are running very high.

Off late, and partly owing to Zakir Musa’s threat to them, Hurriyat leaders have begun facing hostility at funerals. But here, they are allowed their 20 minutes.

Following the Hurriyat leader is other speaker who steps up the tempo a bit, “Let’s introspect into why this person was compelled to take up the gun on our behalf. He died for all of us. We need to acknowledge the reasons. Let’s all promise to keep fighting…”

In time, speaker after speaker, go on to lash themselves and their audience, breathe fire and call on the forefathers’ sacrifices. The crowd, as it swells dissolving private fears and embarrassment, responds with resounding chorus.

“Militant funerals are important social events for two reasons. First because the sort of things that are said here can’t be said anywhere else, in Masjids or in houses, for the fear of police informers. You can call for Jihad, ask people to take up guns, glorify militants, rouse people against India and no one will inform or object to your participation or your choice of words,” said a young journalist who was there to cover the funeral as well.

The other reason is that these functions are the only of their kind that let militants reach out to people. Militant funerals are the only social events in which militants or their supporters can directly address people, create more sympathisers and militants in turn.

'Women, like young boys with video camera phones and journalists, weren’t allowed at militant funerals. They struggled to create their own space and have by now become essential to these events.'

Police doesn’t turn up at the events to avoid further violent backlash.

The gun salute, militants firing in the air at funerals, is a particular crowd pleaser.

Though it doesn’t really please the Over Ground Workers (OGWs) of the militants. One of them we had spoken to a day ago, complained about these gun salutes, “they don’t know how hard we work to get these bullets and then they just waste them all away for public.”

That aside, militant funerals are also events where most of the potential recruits get their first inspiration from.

I met a family of a 14-year-old militant in a different part of the valley a few days later who had no idea why their child had abandoned his school and family to join militancy. His friends later said that the boy was a regular at militant funerals, and had attended funeral prayers of Burhan Wani and Dawood Sheikh. The same story, with some tweaks here and there, we heard from family members and friends of several other militants, we spoke to, who are right now on the run.

While the public speakers keep turning tighter the screws, the emcee interrupts time and again asking people to make way and clear the entry to the ground. Each time he says this, the crowd goes quiet in anticipation of militants.

Militant arrivals in funerals are usually preceded by public announcements in which people are told to make way, “Mehmaan aane waale hain.”

You can call for Jihad, ask people to take up guns, glorify militants, rouse people against India and no one will inform or object to your participation or your choice of words. - A YOUNG JOURNALISTS WHO HAS BEEN COVERING MILITANT FUNERAL.

No such announcement is made here and the militants never come. But that doesn’t prevent people from spotting hidden militants here and there and running after them.

Photojournalists like Shehriyar are often mobbed and have an especially hard time at funerals because of their long hair and high boots.

“Once at a funeral an old man asked me why didn’t I have the 7 kilo, the Ak 47, in my hands instead of this camera. I told him bullets can be heard in just 1 km away, but photographs travel thousands of kilometers,” Shehriyar says.

It’s about 9:15 am now, and there are not less than 7000 people in front of the stage. They’ve come despite severe restrictions, evading police pickets by climbing over hills and walking through farms to reach here.

The sun is blazing now and Lelhari’s body is beginning to bloat. The organisers, basically a group of youth from Lelhari, are aware of this but wait as they see hundreds of people who’ve come from far to participate in his funeral prayers.

Every visitor who comes pays his respects to the brother of Ayyub Lelhari. His brother, and the rest of his family, will now become first among the equals in Lelhari.

A local resident of Lelhari says, “Look what a funeral he’s got. Not even 10 people would’ve come to the funeral had I died. This is what a send-off is. He took our tehreek [movement] forward. Everyone will offer salaam to his brother with respect now.”

'Hundreds rush towards the graveyard where Ayyub Lelhari is to be laid to rest. But only a handful of people are let inside.'

The local boy says that Ayyub in his will had mentioned that he wanted either jailed Hurriyat leader Masarat Alam or his brother should read his funeral prayers.

Since Masarat Alam is still in jail, his brother eventually reads the funeral prayer, twice to accommodate thousands of people in two batches.

As soon as the prayers are done, thousands of people run towards the body, which has begun its trip to the grave where it will be laid with other dead militants.

There is a distinct difference in Kashmir in the manner in which militants are laid to rest. While bodies of dead militants in South are kept at one place, those in North are carried around the village for all to see.

Is there a peer pressure which makes the locals come and necessarily attend these funerals?

Look what a funeral he’s got. Not even 10 people would’ve come to the funeral had I died. - A LOCAL RESIDENT

“The way it works is, if you’re in North and body of a militant is passing in front of your house, you will have to come out. And down in the South if five of your friends return from a funeral they will taunt the other five who didn’t go and then all of them will eventually go to the next funeral. So yes, in a way there is some sort of social pressure as well in attending these funerals,” says an independent photojournalist from North Kashmir.

Hundreds rush towards the graveyard where Ayyub Lelhari is to be laid to rest. The women raise their tempo of slogans. The children climb fence after fence till the graveyard. But only a handful of people are let inside.

Up ahead, in the open field, people are still coming in tractors. Arguments trigger over why the funeral was finished in a hurry. Even after the ceremony is completed nobody’s in a hurry to turn back. Some have travelled over 100 kms to attend Ayyub Lelhari’s funeral. Gossips start about the probable police informers, discussions are held about the ‘haalaat’ and ‘Maslaa-e-Kashmir’. It’s still 10:30. We are in a remote village, far away from hustle and bustle of cities. And the day has just begun.

(A part of 12-part #KashmirBeyondCliches series)

Comments

0 comment