views

It is for good reason that euthanasia remains a favourite, if slightly worn-out, topic with high-school debaters: it's the debate that just keeps giving.

Even if you believe that euthanasia is a good thing in some cases, deciding what circumstances exactly are good enough is really hard, particularly if relatives are waiting in the wings to benefit from a possible inheritance, hospitals are looking to clear a bed, or the patient could miraculously recover or change their mind that they actually really want to continue living no matter how painful that will be.

It's been similarly difficult for the Supreme Court to come to a conclusion.

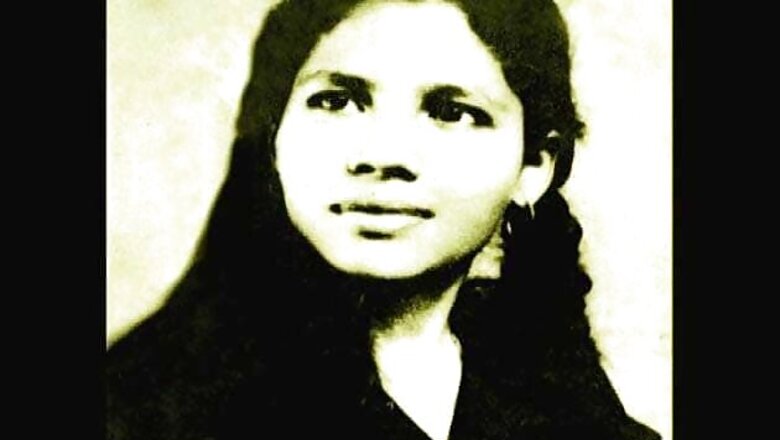

One might think that the euthanasia issue was settled in 2011 when Justice Markandey Katju decided in the highly publicised and emotive Aruna Shanbaug case that so-called passive euthanasia could be legal in certain cases, but active euthanasia couldn't.

Today, the Supreme Court basically decided that Katju had got his law wrong in 2011.

Simply put, passive euthanasia means doctors withdrawing artificial life support of patients in a persistent vegetative state (PVS) with no chance of recovery, while active could mean doctors administering a lethal injection, i.e., actively killing the patient.

The NGO, Common Cause, which describes itself on its website as having "a romance with public causes", has written to the law and health ministries, state ministries and hospitals since 2002 about the issue. Now, in the case currently before the Supreme Court, the NGO had filed a petition to restate that passive euthanasia should be permitted and to push for recognition of so-called "living wills". (A living will would be made in writing by those who would not want to be kept alive in circumstances such as PVS).

The basic argument of the NGO is that not allowing those in a persistent vegetative state (PVS) the freedom to choose to die, deprives them of their right to "to refuse cruel and unwanted medical treatment", such as artificially feeding, breathing for or otherwise keeping the patient alive with tubes, machines or a cocktail of drugs.

The counterargument advanced by the government in this case, is that doctors have a duty to save patients' lives, and euthanasia is expressly prohibited at the moment under the Indian Medical Council rules.

In short, the government is saying that "the basic desire of a person is to get treated and to live", according to the NGO, while the NGO's basic point is that if there is an express wish not to be treated, treatment shouldn't be forced on patients.

So far so good, philosophically. But the potential factual variations in such cases are so complex and nuanced that it has proven difficult for the courts to come up with any good rules that apply to all.

From a purely legal point of view, there is a conflict between two different Supreme Court judgments: one from 1996 (Gian Kaur vs State of Punjab), with the other being the Aruna Shanbaug decision.

In Gian Kaur, the Supreme Court, a little confusingly, decided two things:

1. the constitutional "right to life" does not include the "right to die", but

2. the "right to live with dignity" does include the "right to die with dignity".

But the Supreme Court there also failed to come up with any practical rules, deciding instead that the debate even in passive euthanasia cases was "inconclusive". The judges effectively passed the buck to lawmakers, requesting Parliament to come up with laws regulating euthanasia. That has not happened.

In the Shanbaug case in 2011, Katju was similarly hesitant to start pronouncing new practical rules on the legality of actively assisted suicide but relied on Gian Kaur in making passive euthanasia permissible.

However, today the Chief Justice of India P Sathasivam and two other judges decided that Katju had basically got the law wrong in 2011 by misinterpreting the Gian Kaur judgment.

So, since its a matter of constitutional interpretation and importance requiring the overturning of the 1996 constitution bench, Sathasivam decided that five Supreme Court judges will now have to hear the arguments on euthanasia to fix the vagueness left by the Gian Kaur and the Shanbaug decisions.

In other words, we're back at square one, and it won't be easy for the Supreme Court to navigate this moral morass for the nth time.

(Kian Ganz is Legally India's founder and publishing editor)

Comments

0 comment