views

Our minds may be tabula rasa, but it is the expiration and the discovery that lead us to enlightenment and wisdom. The process is even more fascinating and elaborate when you live in India — “the cradle of civilisation”. The tradition perhaps continues to flow perennially, as if the waters of the Ganges, since the beginning of ages. Here, we have a plurality of ethnicity, thoughts, theories, ideas, and ideologies; they together constitute the very fabric of Indian culture. Hardly any other civilisation matches this accommodative stance which India has shown since the inception of history.

Again, these pluralities were further substantiated by voluminous literature, be it Vedas, Aranyans, Upanishads, Agamas, Tripitakas, Puranas, epics, etc; these rivers of thoughts have always quenched the intellectual thirst of Indians and humanity at large.

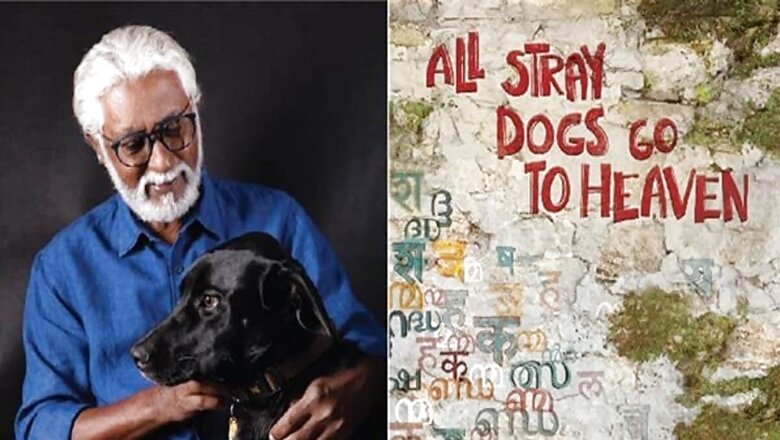

In this backdrop, Krishna Candeth’s debut novel, ‘All Stray Dogs Go to Heaven’, discusses in detail how exploration and pluralism lead to the intellectual foundations of a being. Told from multiple perspectives and weaving past and present dreams and reality, the book revolves around relatable themes and emotions.

Let’s ask Krishna himself about this fascinating journey of his. Excerpts of the interview:

Writing the debut novel at the ‘tender’ age of 70, what inspired you to fare in these seas?

It was more like plunging down a river — a little deeper every day, not knowing what lay in its depths. All writers dredge for stuff — in their own lives and the imagined lives of others — but it is how they use it in their work that is both mysterious and interesting.

I spent four years at the Film School, Columbia University, learning to write and direct films. Filmmaking is an arduous process — you’re expected to write the film, assemble a cast and technical crew, direct the film, publicise and exhibit it and raise the money in order to be able to do all that! The honest truth is that I was no good at raising money and at some point while working on a project, I decided to shelve it and write a novel instead. It wasn’t really a huge jump because I had carried bits and pieces of the novel with me for a long time.

This work shows the profoundness of your scholarship and experiences, which among these two, you think, have dominated your writing more?

Everything, they say, is grist to the artist’s mill. More so when you’re working on something, be it a poem, a screenplay or a novel. A gesture, an overheard conversation, an object recovered from a dream, something you read or observed — everything suddenly seems to point back to what you’re working on.

American artist Leo Cherne used to say that nothing is wasted in a man’s life. One doesn’t need a great deal of scholarship or experience to produce something that may move and affect others; one needs to be true to the parallel worlds of imagination and experience that each of us carry within ourselves, and learn to explore and mine that world to one’s advantage.

There are artists and writers who have led meticulously ordered lives, never moving away from the town or city where they were born, who have succeeded in creating a magnificent world that has sprung wholly from their imagination.

I found your description of scenes to have a Ruskin bond style, while your issues were somewhere closer to Jordan Peterson and like intellectuals. How far do you agree or disagree with this?

Here’s a confession. I have read neither Ruskin Bond nor Jordan Peterson. So no danger of influences there!

This book well depicts cultural pluralism in India, how far, as a nation and a civilisation, can we accommodate it along with our spirit of oneness?

It’s been well documented that the concept of a pluralistic culture has been prevalent in India since ancient times. It has always been a defining and enlightening feature of the civilisation we belong to. Ethnically and linguistically, diverse groups have always lived side by side in India and it is quite wonderful (and instructive) to remember that over time, the traits or customs of any one group were considered worthy of being added to, and in turn, enrich the dominant culture.

It is, of course, obligatory that this pluralistic society of ours survive and thrive, and we must think hard about how we go about making that possible. We can survive by being prejudiced and ruthless and egotistical but history has shown that way to be chaotic and ruinous. Conversely, one can learn to live together as one does in large cities, grow more tolerant, and, if nothing else, at least refine one’s prejudices in the process. What is imperative is that we continue to work privately and through groups and organisations to create and maintain a public consciousness of what a pluralistic society stands for and means, and how urgent it is that it survives.

In the years following Independence, it seemed the most normal thing to have Sikhs, Muslims, Parsis and Anglo-Indians in the cities I lived in and the schools I attended. We were a happy, diverse bunch of kids and not once, as far as I can remember, did religion ever mar our friendships or social relations. I suppose that was a different time — more idealistic, perhaps — and one had the sense that our parents, no matter what strata of society they belonged to, were all in it together, creating a post-independent society that they were only dimly aware of.

From Buddha to Nitya, you have shown that enlightenment comes from exploration. Please elaborate.

Yes, exploration, but of an inward nature. With Nitya, it begins when, as a young man, the theyyam tells him that he has “forgotten to live.” He doesn’t know what it means but in the course of the novel when he joins Chinma and his group, on their voyage towards some form of mental and emotional discovery, he begins to understand that he has forgotten to live because he doesn’t know or has forgotten how to love. He will remember to live again by the simple process of learning to open his heart.

The Buddha’s case is, of course, more complex and fascinating. We have this fixed and rather unfair image of him as a permanently enlightened person but it is useful to remember that he was once a young man with a dilemma. He was 29 years old (with a young son Rahula who was 13) when he walked away from the kingdom he was born to rule, and decided to dedicate himself to finding an end to the suffering that he rightly believed was the curse of our earthly existence.

Buddha was only 35 when he declared himself “illumined”, but what we tend to forget is that he would live on for another 45 years, gathering disciples and courting patrons who would support his teachings and the new way he was propagating how to live in the world.

One of the characters in the novel refers to him affectionately as Dr G. Buddha because he was “an uncommon doctor who took the most revolutionary reading of his own pulse, diagnosed his disease as a case of chronic suffering, and then wrote up, for himself and humanity, a series of prescriptions to alleviate that permanent condition.”

Surely the Buddha is the most advanced and marvellous case of inner exploration and understanding ever undertaken by a living human being that would revolutionise the world and benefit generations to come.

Lastly, how far are you personally inspired by the philosophy of Charvaka and find it a possible solution to our societal problems?

As philosophy students at the University, Nitya and Chinma are seduced by the teachings of the Charvakas, who were great nomadic philosophers of the 6th century BC. They were sceptics who rejected Hindu rituals, scoffed at concepts like karma and reincarnation, and proclaimed that the only true way to perceive the world was through the senses. Pleasure was, for them, the organising principle of life.

During the course of the novel, these early beliefs of the two friends begin to evolve and undergo a profound change. They realise that to continue to believe in the Charvaka philosophers is to lead selfish, egotistical and, ultimately, meaningless lives. For their lives to have any meaning at all, they had to be linked to the lives of others. Real responsibility began when you were responsible for other lives that were linked to your own.

It is a marvel that the vibrant school of Charvaka philosophy existed at all, and that too as early as the 6th century BC. But to think of it in any serious way as an answer to our present-day problems wouldn’t be very productive! If anything, the principle that connects us all today is one of vulnerability, and being exposed at various levels to the same set of emergencies, whether it be higher costs of living, immigration, continued discrimination or climate change.

The way to confront these various problems is certainly not by wholly dedicating ourselves to a life of pleasure as the Charvakas did!

Read all the Latest Opinions here

Comments

0 comment