views

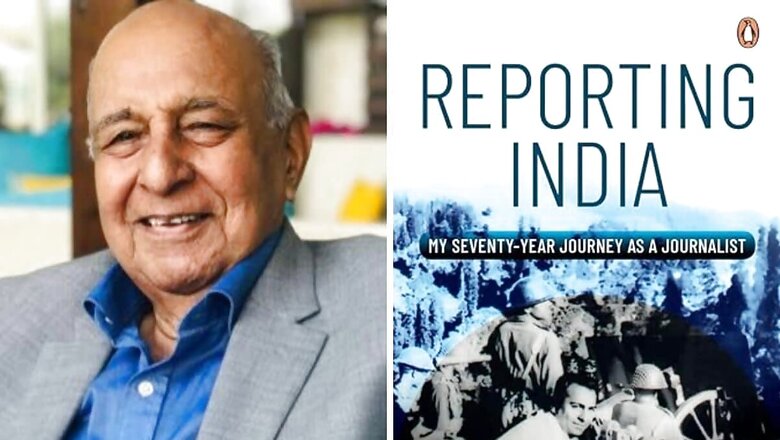

Veteran journalist Prem Prakash, with a unique distinction of covering the journey of India from first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru to serving Prime Minister Narendra Modi, has several books, including Reporting India and Afghanistan: The Quest for Peace, The Path of Wars, to his credit.

In an exclusive interview, he talks about his books, rich experience in journalism (as the Founding Chairman, Asian News International-ANI) and his upcoming book that chronicles India’s freedom struggle against the British empire through a fresh angle.

Q. In your book Afghanistan: The Quest for Peace, The Path of Wars, you delve into Afghanistan’s history, from Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s influence to the present day. What motivated you to explore and document this extensive historical journey?

A. As far as Maharaja Ranjit Singh is concerned, you must know, a lot of books have been written on Afghanistan, largely by Western writers. And they all say that it is impossible to subjugate Afghanistan. But they have all ignored, whether it is deliberately, or it is lack of knowledge, or it is lack of doing research work, whatever.

The fact is Maharaja Ranjit Singh subjugated Afghanistan, had his victory parade in Kabul, went over to Ghazni to say, where was this Mahmud of Ghazni who attacked our Somnath temple so many times? And he found to his horror that the gates of Somnath temple were there at the gates of his tomb. He removed those gates and also brought them back. So, I thought it is better that I tell the world to stop this nonsense that Afghans have not been subjugated. They were not only subjugated, but then Maharaja Ranjit Singh, in order to secure the empire of Punjab. Punjab was very big during his rule and that was known as empire. To secure the empire of Punjab, he annexed Peshawar valley, which means annexed Peshawar city, which belongs to Afghanistan.

He annexed the Khyber Pass, which again belonged to Afghanistan. He annexed all the Pakhtoon areas attached with it. So when you see today is the whole of that area, what is known as Durand line, it was known as Ranjit Singh line, originally belonged to Afghanistan. And he annexed all that and the two Anglo-Afghan wars later on were fought only because Afghans wanted those territories back. So you wait and see what will happen now between Pakistan and Afghanistan, because whatever government they have in Kabul, Afghans will not stop asking once again, hey, give us back our territories. So that was what prompted me to tell the world that there was a man in India, Ranjit Singh, who captured Afghanistan and did all this.

Q. You highlight the liberal and stable Afghanistan under King Zahir Shah. How has the country’s past influenced its present, particularly in terms of governance and societal norms?

A. Remember Afghanistan was originally a Hindu state. Now that’s a different story, that will take me a long time to explain to you how it became pan-Islamic or whatever. But the relationships, all that, Zahir Shah was a very forward-looking king. And Zahir Shah also realized that Afghanistan was largely a tribal area. Each tribal head is like the king of his own tribe. So he kept his relations very friendly with all tribal heads. And when he kept his relations with tribal heads so friendly, there was peace in Afghanistan. And during this period, education grew. The education grew.

The country developed. And it was, imagine, French schools during this period. Prosperity was there. So it’s all that. It was a pity that his own first cousin, Dawood, when he was away for treatment, overthrew him and captured. But even Dawood’s period was okay, because I went there for the first time in Dawood’s period also. So let’s see. The book discusses the role of the US and Pakistan in the creation of the Taliban. How do you perceive the geopolitical dynamics that contributed to the rise of the Taliban? You see, it is like this. When Dawood was ruling, remember, there was a Cold War in the 70s between the USA on the one side, the Soviet Union, thought to be the Soviet Union. Now it is Russia. The Soviet Union was on the other side. Now in this Cold War, America was very keen that Russians should not or Soviets should not move successfully into Afghanistan. When Dawood was overthrown, why was Dawood overthrown? India has managed to secure Afghanistan into non-aligned countries. Unfortunately, Iran was also among the non-aligned countries.

Iran at that time was ruled by Raza Shah Pahlavi. Now Raza was very, as good as a stooge of Americans. And Americans used him wanting to bring Afghanistan into their fold. Raza convinced Dawood to call for a meeting of the non-aligned foreign ministers. The Soviets did not approve of it. Remember, Soviets were almost not really fully running, but as good as running the country in the sense that thousands of students used to go to the Soviet Union from Afghanistan for studies. The Afghan army was fully financed by the Soviet Union. More financial aid used to flow in from the Soviet Union. Afghanistan itself had only income from dry fruits and things like that, nothing more. And the reason why Soviets were against it, they had seen at that time there was this gentleman in Yugoslavia, Marshall Tito, who was also a communist leader, but he had gone into the non-aligned movement. Again, he had broken away from the Soviet bloc. So when they saw that Dawood was doing that, they overthrew Dawood.

And obviously a communist government headed by Mohammad Tariqi was established in April of 1978 in Afghanistan. So that is the beginning of your question about, if I remember correctly, how the Taliban and all that happened. When this happened, Tariqi lasted about one year. There was inner trouble among the communist party there. And then Tariqi was killed and Mohammad Amin came. Americans then tried to win Mohammad Amin over. The Soviets were again aware of it. You see Afghanistan was now becoming a center of American and Soviet struggle between the spies of the two countries.

Indians were of course watching it. Mohammad Amin was assassinated and Soviets brought their own man there who then invited the Soviet army to come into Afghanistan and help him. Because things were getting out of control for the interference of Americans were becoming too much. Now this happened at the end of December of 1979 and I was there. I landed there again at the same time again. And well, there were Soviets everywhere. So the fighting began. When the fighting began, again the Americans were shocked. They found that the Afghans were not bothered. That another person had taken over. I heard that the communists were there. Afghans were carrying on their life as it is. So first they created Mujahideen. That didn’t help. Then they created, ultimately they created what was Taliban. Taliban were, you see at the war, when the war created thousands of, the whole country was by now disrupted, Afghanistan. People started going as refugees to Iran. People started going as refugees to Pakistan, largely to Pakistan.

Those who could afford, many came to India. Particularly Hindus and Sikhs came to India. Muslims also came. And so from these camps they picked up these youngsters and trained them thoroughly into extremism, which is not even there in Islam. You know, there’s this kind of extremism. It’s not there even in Islam. And they gave them the title Taliban because Taliban means student. They were students’ only, young fellows. This is the creation of the Taliban. They were inducted into the war. Now these Taliban, these young students from the camps had no longer any tribal affinity. These were not there. And so this became a different kind of war. The tribal affinities were gone virtually by now.

Q. Your narrative emphasises the search for peace in Afghanistan. What do you believe are the critical steps needed to pave the way for lasting stability and harmony in the region?

A. You see, for that I will quote to you the words of Ahmad Shah Massoud. Ahmad Shah Massoud was a leader from Panjshir in northern Afghanistan. He had control over Afghanistan for a while. And he was unfortunately assassinated by this. He was assassinated by the American men. And he had said in an interview with ANI that peace can come to Afghanistan when foreign powers stop interfering in its affairs. So if Americans, the Russians and all of them stop interfering and leave Afghanistan alone, maybe peace will return. India was giving as much help as whatever we could afford. Maybe we could have done more.

Q. With your extensive experience as a photographer, film cameraman, and columnist, how do you see the evolution of journalism and storytelling in India over the past several decades?

A. Well, journalism has grown. It’s not that it’s not grown. You see so many things apart from the newspapers. India is now flooded with private TV channels. It used to be the state-run network only at one point of time. Now it is flooded with TV channels. So journalism has grown manifold in India.

Q. Having covered major events in India’s history, which story or incident had the most profound impact on you personally, and why?

A. Well, well, well. It’s a sad question to me because the 1962 war had its most serious impact on me in the sense that I was covering the defeat of a country. And remember, also I want to tell you that I was among the only two Indian journalists when most of the Indian journalists fled from the North Bank of Assam. When Jawaharlal Nehru declared his sympathy for the North Bank had been lost. We had lost in Sela.

The Chinese were marching down. They almost came to the foothills of what is known today as Arunachal Pradesh. They almost came to the foothills of that area. And we were the only two Indian journalists and we saw all that. So that left a lot of impact on me. What a sad thing that has happened to India. That’s why ever since then, I never want to see that the Indian army or Indian defense forces should be made weak in any manner. Of course, no prime minister has had the courage ever since to weaken the army. But then there have been instances, I can tell you in between. Let’s not forget about that, where modernization has been ignored. That is what had happened earlier to the Indian army, which was the world’s most powerful army during World War II. Remember in North Africa, it was the Indian army which turned back the tide of World War II when it fought Rommel. Rommel was Hitler’s blue-eyed general. His forces were turned back by the 4th Indian Division. And it was this very 4th Indian Division which was beaten at Sela. In what is known as Northeast Frontier Agency, NEFA, today is Arunachal.

There can be many others like there was no need to send an army into the Golden Temple. There was no need. This could have been solved. After all, Bhindranwale was the creation of the Punjabi Mafia which had surrounded Mrs Indira Gandhi at that time. Bhindranwale could have been dealt with by the police. Also the manner in which we had treated General Shah Baig who was a Prime General of India, inaugurated by the British during World War-II and who had done so much for us to liberate Bangladesh. He had been dismissed by General Rana for something.

Q. Your book spans significant political shifts, including the Emergency and the rise of leaders like Narendra Modi. How has the landscape of Indian politics changed, and what challenges and opportunities do you foresee in the future?

A. The Emergency was a black spot in Indian democracy history. But anyway, Mrs. Indira Gandhi at heart was a democrat. I still believe that although I had my difference of opinion with LK Advani on that. He felt differently. I said that if she had not been that, why could she have gone for the election within two years of Emergency? An election in which she lost. The Janata Party couldn’t rule properly. You didn’t get a proper government. So, to that, to see that various Prime Ministers have been there since then and of course, we have now come to the point of Modi. Now, I have not covered Modi directly myself because, again, I’m no longer in the field. The whole team is in the field, but I’m not in the field.

Q. Both your books cover a wide range of historical and contemporary events. How do you approach the storytelling process, and what message or insight do you hope readers will take away from your works?

A. How do you approach the storytelling process and what message or insight do you hope readers will take away from your works? It’s not really storytelling. Remember, I’ve been one of those few journalists and I would still say that real journalism calls for a person to go in the field. I’m one of those few people who have always been in the field. So, I was able to tell things as an eyewitness. That’s how I can read everything in my book, my 70 years’ journey and whatever events happened during those 70 years including the liberation of Bangladesh, which was a huge story which I covered. Those are all eyewitness accounts.

Q. As a pioneer in the field of Indian journalism, you’ve witnessed the transformation of the media landscape. How do you see the role of journalists evolving in the digital age, and what advice would you give to aspiring journalists navigating the challenges of today’s media environment?

A. I have no right to comment on how the journalists work today. But there is a role for an editor and there is a role for a journalist. The role for the editor is opinion. For example, today I am in a position where I can give my opinion. When I was a journalist in the field, I had to be away from any opinion. I have to report the facts as they are.

Now, what I find most annoying today, whether you watch the TV channels in the evening, they are all giving their opinion. Yes. It’s not letting you know of simple straightforward facts. They are not giving you proper straight news but they are giving their opinion. And maybe that is what the people want also. It’s a masala. So, I would say that journalists should stick to reporting the facts. Leave it to the editors and others who are commentators to give their own opinions and things like that and analysis. Like the editors in the newspaper used to do. Edit page, you give comments and so on. But other pages will only carry factual stories. So, that means the conventional sense of journalism will stay here. It’s not going to wither away anytime soon.

Ashutosh Kumar Thakur is a Bengaluru-based management professional, literary critic, and curator. Views expressed in the above interview are solely those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

Comments

0 comment