views

There’s something disconcerting about democracy: It often works at cross-purposes, acting as much to strengthen democratic forces as to empower their existential adversaries. One saw them with the Americans, who, for decades, worked in close coordination with the dictators of West Asia while at the same time colluding with their detractors in the name of democracy.

So much so that Hosni Mubarak, who ruled Egypt with an iron fist for three decades until 2011, when he was dethroned by the Arab Spring, a result of the grand American wet dream to turn West Asia into a paradise for democracy, once rebuked a top American diplomat, saying if he followed what he exhorted, Cairo would be ruled by Islamists.

Sadly, the Arab Spring saw a series of West Asian countries overtaken by Islamists through electoral processes!

This propensity to run with the hare and hunt with the hounds makes the democratic West, especially America, a difficult, if not dangerous, friend to have. As a popular saying in the diplomatic parlour goes, it’s perilous to be America’s enemy, but it’s even more perilous to be its ally or friend.

India, publicly termed “a natural ally” by several top American leaders of both Republican and Democratic credentials, has been particularly targeted in recent years, whether on the issue of Khalistan or the façade of sliding democratic, secular values in the country.

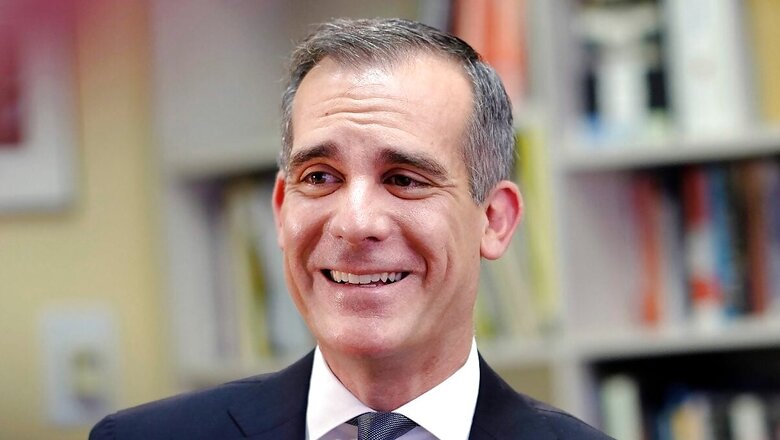

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Moscow visit has further upped the tempo of American scrutiny vis-à-vis India. The US ambassador to India, Eric Garcetti, has gone to the extent of saying that “strategic autonomy” cannot apply in times of conflict and that India and the US should uphold principles when other countries go against the rules-based order or violate sovereign borders.

“I know… and I respect that India likes its strategic autonomy. But in times of conflict, there is no such thing as strategic autonomy. We will, in crisis moments, need to know each other. I don’t care what title we put to it, but we will need to know that we are trusted friends, brothers and sisters, colleagues…,” Garcetti was reported as saying at an event organised by a defence think tank in New Delhi.

For those unversed with the complications of Indo-American power dynamics, Garcetti’s ‘undiplomatic’ comment may seem reasonable. For, “trusted friends, brothers and sisters, colleagues”, as he describes the India-US relationship to be, need to stand up for each other. But, then, has the US really stood up for India, especially in recent years? Has it curbed the thriving anti-India ecosystem in American colleges, academia, media, think tanks, and, of course, in a section of the administration, especially the state department? And, most importantly, has it done anything to counter the growing sentiment in the Indian corridors of power about the invisible Western hand working overtime before and during the 2024 Lok Sabha elections to subvert the electoral outcome against the current dispensation?

Garcetti should realise that the American stand vis-à-vis India, especially since Narendra Modi came to power, has been dubious, to say the least. It seems to be engaging with India as well as pushing it into the corner — almost simultaneously. It would shake hands with the Prime Minister of India and also collude, indirectly, of course, with the forces looking for ways, democratic or otherwise, to dislodge him. It would seek India to be a partner in an anti-China alliance but would continue to dodge the Indian demand for the transfer of critical technologies. It would want Delhi to disengage with Moscow and Tehran, but would continue to indulge Pakistani generals.

The US needs to know that it has crossed the ‘Lakshman rekha’ several times in recent years. It has allowed a Khalistani terrorist on its soil who, on a regular basis, threatens to bomb India’s Parliament. It corners New Delhi on not-so credible reports accusing India of extraterritorial killings on Western soil. It gleefully brandishes the so-called democracy, religious freedom, and human rights reports of American institutions, whose anti-India biases are hardly difficult to discern. And, above all, it has been seen to be acting as a facilitator of forces working overtime to enforce a regime change in India.

Now, that’s not the way a friend, far less an ally, should work. But then, as the saying goes, it’s more dangerous to be an American friend than to be an American adversary!

It is against this backdrop that Prime Minister Modi’s Moscow visit should be looked at and analysed. It just cannot be accidental that the Indian Prime Minister was in Moscow just when a significant NATO summit was taking place in Washington. In fact, as reported by the Washington Post, the “Moscow meeting came despite concerns conveyed to New Delhi by several senior administration officials earlier this month that the timing would complicate the ‘optics’ for Washington”.

The US-based newspaper explained how Deputy Secretary of State Kurt Campbell, among others, even spoke with Foreign Secretary Vinay Kwatra in early July “in hopes that the Modi-Putin encounter might be rescheduled to avoid coinciding with this week’s summit”. This year’s NATO summit, after all, was commemorating the 75th anniversary of the military alliance’s founding, and its members were seeking, as the Washington Post reported, “to signal strong support for Ukraine in the face of Russia’s aggression”.

Prime Minister Modi’s visit has given Putin a new lease of life globally. After all, this wasn’t the visit of a dictator from a pariah state like North Korea or a strongman from a democracy-deficit nation like China. India is a democratic powerhouse, with or without Western legitimacy. India is an economic giant, currently placed in the fifth spot in the global ranking and slated to take third place in 3–4 years. The Modi visit also signifies the fast crumbling of the anti-Russia alliance led by the US, more so at a time when Moscow is seen to be making a great economic turnaround despite Western sanctions and wars.

This, however, doesn’t mean that Prime Minister Modi visited Russia just to put the US in its place. Yes, the symbolism of the Moscow visit at the time of the NATO summit in Washington cannot be missed, but the fact is that India has, from Day 1, made it clear that Ukraine isn’t its war. It’s a war that the US-led NATO has imposed on the world with its anti-Russia obsession, even when there were enough indications suggesting that Vladimir Putin, to begin with, was willing to be a part of the US-led Western order. Two, geostrategically and militarily, Moscow remains a non-negotiable partner for New Delhi, given its geographical location next to China, an adversary without a doubt, and also India’s continued dependence on Russian arms.

There is no way India could have acted in any other way on Ukraine. But yes, had the Americans shown diplomatic heft and caution, maybe the timing of the Modi visit would have been more favourable to the West. But then, for that, the US administration has to realign its notion of diplomacy with what author-entrepreneur Bo Bennett once said: “Diplomacy is more than saying or doing the right things at the right time, it is avoiding saying or doing the wrong things at any time.” Now that’s a big task for a nation that prides itself on being a democracy, works overtime to export the idea of a free world to other countries, and yet doesn’t mind winning and dining with the worst of dictators, besides indulging in occasional regime change attempts across the world.

Uncle Sam, you cannot have the cake and eat it too — all the time.

Comments

0 comment