views

An air of the surreal dominates the discourse in Pakistan’s February 8 elections. The campaign has been lacklustre, with the absence of a level playing field and expectations of a pre-determined outcome, favouring a weak PML-N coalition. This impression was strengthened with three quick judgments in succession by courts last week, imposing long incarcerations against former prime minister Imran Khan. This seemed a brazen message from the powerful military establishment to the latter’s die-hard fan club that he would not be allowed to play any political role in the foreseeable future.

The electorate comprises 128.5 million registered voters, out of a total population of 241.5 million. This includes almost 57 million young voters between the ages of 18 and 35, comprising 47 percent of the electorate. The strength of the national assembly (NA) is now 336, comprising 266 general seats. Sixty seats are reserved for women and 10 for non-Muslims. These are allotted to political parties based on proportional representation. The magic numbers for forming the government are 134 and 169, after the addition of reserved seats. Of the 266 general seats, Punjab has 141, Sindh 61, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) 45, Balochistan 16 and the Federal Capital area of Islamabad three seats. Punjab has more seats than the other three provinces combined. The party, which controls Punjab, controls Pakistan. Provincial assemblies (PA) will also be elected simultaneously. Punjab has 371 members (MPA), Sindh 168, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 145 and Balochistan 65 seats. A total of 5,113 candidates are contesting the NA elections while 12,638 candidates are in the fray for the PA elections.

After the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) was denied the ‘bat’ symbol, it will not be in a position to claim its proportion of reserved seats for women and minorities. At least 63 percent of Independent candidates are contesting the NA elections and 66 percent remain in the PA field.

After the army blessed thrice elected former prime minister Nawaz Sharif’s return from almost four years of exile in the UK and the judiciary followed suit, giving quick relief in cases against him, reducing also a life disqualification to five years, the PML-N seems poised to recover lost ground in its main bastion, Punjab. Despite this boost, Nawaz seemed rather listless in the election campaign, obsessing mainly on past injustices against him. He did not attack the military establishment. His dilemma has been to search for a counternarrative to offset Khan’s persisting popularity. He also has to decide who should inherit his mantle, whether charismatic daughter Maryam or docile brother, Shehbaz Sharif, who remains more acceptable to the army.

The People’s Party of Pakistan (PPP) retains its main political base in Sindh, depending on support from rural landlords. It has lesser control in urban areas of Karachi and Hyderabad. After performing creditably as foreign minister in the last coalition, Bilawal Bhutto Zardari has been trying hard to enhance his acceptability to the army as a young, articulate and balanced leader. Choosing to contest from Lahore, he has also tried to wrest back an erstwhile vote bank in Punjab. His father, Asif Zardari is a more experienced and wily political leader. These two have been playing good cop and bad cop, occasionally criticising past allies. The latter has tried hard to stitch support from motley feudal in Balochistan and South Punjab. This may stand him in good stead in the presidential election stakes, which must follow the senate elections in March 2024. The present president, Arif Alvi, who was elected with PTI support is holding on to his post. His term ran out in August 2023.

The PTI has its main stronghold in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. It has held government reins there since 2013. It made sizable inroads in Punjab after Khan was thrown out of power by a vote of no confidence in the NA in April 2022 by launching a narrative of “foreign conspiracy”, “unfair martyrdom” and “desertion by the military establishment”, as reasons for his ouster. After the Punjab bypoll in 2022, he seemed electorally invincible. In a series of public meetings, senior military officers were disparaged by name. Though later exposed as false, this narrative has been fanned by an army of besotted, young social media trollers, who have now become a headache for army censors! Despite several derogatory audio and video disclosures, Khan’s popularity has not been affected by attempts to besmirch his character. This is a new phenomenon, emerging as a political idea, especially with unemployed youth and women voters in urban areas, which reflects growing distaste for the reality of the army’s extra-constitutional control of power in Pakistan, instead of elected politicians or Parliament.

There are other smaller parties like the Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (JuI-F) of Maulana Fazlur Rehman and the Balochistan Awami Party (BAP), which have pockets of strength in southern KP and northern Balochistan. The Istehkam-e-Pakistan Party (IPP), a faction of the old PTI with sugar baron Jehangir Tareen as its leader, could win a few seats in Punjab, as may Pervez Khattak’s PTI (Parliamentarians) in KP.

The Karachi factor will come into play too. This time, of Karachi’s 21 seats, the Muhajir Quami Movement (MQM), which had pockets of strength in Greater Karachi in the past, is aiming for 12 to 14 seats to offset the PTI’s gains in 2018. Factions led by Khalid Maqbool Siddiqui, Farooq Sattar and Mustafa Kamal’s Pakistan Sarzameen Party (PSP) were herded together under the army’s none-too-gentle prodding. However, this “union” has yet to be “blessed” from London by exiled MQM “imam” Altaf Hussain. The Jamaat e Islami (JeI) could also try to build on its strong showing in the local body elections to win back a few of its traditionally held seats.

Two Islamic fundamentalist parties are also in the fray, furthering the military establishment’s past plans of “mainstreaming” them, the Markaz-e-Muslim League (MML) backed once by Hafiz Saeed of Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) fame, and the Tehrik-e-Labaik (TLP) led by Saad Rizvi, son of late Khadim Rizvi, who had organised the Faizabad crossing agitation in 2017 at the army’s behest to destabilise the Nawaz Sharif-led government. Saad galvanised the TLP to emerge a credible third in all 14 seats in Lahore in 2018. He condemns the anti-army May 9 violence from last year but does not support the mass arrests that followed. This time, while he may not win much in Punjab, he could make inroads in Greater Karachi.

Electable feudals from southern Punjab usually “go with the wind”. This time, the perception in Pakistani political circles initially suggested that the PML-N was being favoured by the army. However, with many Independents now in the fray, bets may be hedged.

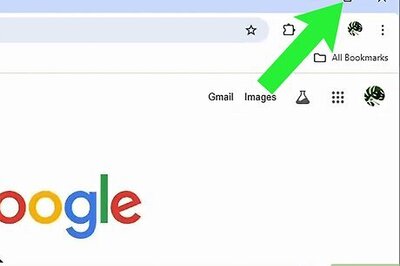

Voter turnout will be a crucial factor on February 8. Turnouts in the last two elections in 2018 and 2013 remained around 52 percent. In earlier elections, it was lower at 44 percent in 2008 and around mid-40s generally. One view is that given the strong signals from the army, the PTI voter will be discouraged that his vote will go to waste. A contrarian view suggests there is perceptible anger against such measures, which may add a sympathy wave in the PTI’s favour. This could be channelised effectively enough by PTI’s social media trollers, to correctly advertise the symbols allotted to its candidates left in the fray. Its supporters still hope for a landslide turnout in PTI’s favour on election day.

Army chief Gen Asim Munir will seek to ensure that the PTI does not win a majority. It may be recalled, in June 2019, he was removed as director-general of the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) after a mere eight months on the job, when he complained to then prime minister Imran Khan about corruption by his wife’s relatives and friends. Khan’s entire strategy in the build-up to the army chief’s succession in November 2022 focused on making it controversial, in the hope of getting his favourite, Lt Gen Faiz Hameed, Munir’s successor as D-G ISI to become the new chief.

As chief of army staff (COAS), Gen Munir inherited a divided senior army leadership. His retirement date as lieutenant general had to be extended by two days to keep him seniormost among contenders. Two of his peers, Lt Gen Azhar Abbas and Lt Gen Faiz Hameed took premature retirement. Gen Bajwa promoted and posted 12 new lieutenant generals just before he retired. Over the next 12 months, Gen Munir has had to bide his time, to slowly get his officers into plum positions. This included giving an extension to the current D-G ISI, Lt Gen Nadeem Anjum.

Sensing the persisting sympathy among youth for Khan, both Munir and Nadeem Anjum have addressed gatherings of university students recently, responding rather candidly to questions about civil-military conflict and the inability of civilian governments to complete their tenures. They have tried to explain this fragility as misgovernance, which did not give them a licence to continue in office. Whether these efforts will hold water remains to be seen.

The post-election scenario will be of interest, as to how the army cobbles together what is being referred to as by Pakistani journalists as another “hybrid pro-max” dispensation. If the PML-N wins between 90 to 110 seats only and the PPP about 40 from Sindh, a bloc of about 20 to 30 Independents, some with secret leanings towards the PTI could play an important role. If elected Independents affiliated with the PTI switch allegiance after being elected to any one of the registered political parties, they could pose a problem and claim representation also to a share of the reserved seats for women and minorities. They will be subject to immense pressures, both of lucre and the rod.

Whatever civilian dispensation is finally entrusted reins of power, its legitimacy will remain doubtful in an election that is seen as lacking credibility. Challenges faced by it will be complex, including a difficult economic situation and a rising wave of terrorism, especially in parts of KP and Balochistan. The army would like to continue interfering in economic management, after the role given to it in the Special Investment Facilitation Council (SIFC) by the last PDM coalition government. Instead of a broad-based political consensus, domestic polarisation between PML-N, PPP and PTI will intensify, not reduce. All this does not augur well for a stable Pakistan or a full tenure of the new government.

(The writer is a former special secretary, Cabinet Secretariat. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely that of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views)

Comments

0 comment