views

This year’s Union Budget for the first-time mentioned energy transition, not once but four times, displaying the government’s intent to follow through its ambitious pledges at COP26 in Glasgow last October, but specific allocations for the renewable energy sector were few.

Indeed, with the COVID-19 pandemic entering its third year, there were expectations for a consumption side impetus given the drastic fall in disposable incomes in the informal sector. This was an expectation particularly from the country’s sprawling Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs), which have borne the brunt of the contraction in demand.

Promoting Renewable Energy Growth

Having said that, the highlight of Budget 2022-23 for the renewable energy sector was the announcement of an additional allocation of Rs 19,500 crore towards indigenising high-efficiency solar module production. The government intends to disburse these funds through the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme, which it announced during last year’s Budget, with the Indian Renewable Energy Development Agency (IREDA) acting as the nodal implementing department. The PLI scheme is an attempt to boost domestic manufacture of a wide range of goods by providing supplemental funds to entrepreneurs who pledge investments toward localising production to substitute imports.

While the government acknowledges the dearth of local manufacturing in the renewable sector, the qualifying criteria of 1 GW manufacturing capacity has meant that only large investors could participate in the bidding process. Nevertheless, the PLI scheme is expected to give the much-needed support to develop and produce high quality solar photo-voltaic panels with the aim to make India an export hub.

Policies with Implications for Renewable Energy Sector

While several sectors found no specific budgetary allocations, it is encouraging to see first-time mentions, like Distributed Renewable Energy (DRE) systems in hard-to-reach border villages of the country with sparse populations where extending the power grid has been a challenge. The Vibrant Villages Programme envisions installing DRE systems – meaning producing energy, typically wind, solar and biomass or a hybrid of the three, closer to the site of consumption, with battery storage backing up for the variability of power production.

DRE systems can be designed to be more climate resilient. We have long argued for this model of energy production as a measure to expand energy access, while also limiting the sector’s carbon emissions, environmental costs and transmission and distribution losses associated with centralised production systems. Given the slim profit margins in DRE systems, an integrated and dynamic policy, specific budgetary allocations and multiple financing options would encourage the DRE sector to participate actively in making the grid infrastructure more resilient in rural areas.

Another highlight of the Budget is the announcement of a Battery Swapping Policy, coupled with the decision to accord energy storage systems “infrastructure” status. This is expected to address space constraints for charging infrastructure in urban areas, and to accelerate the adoption of electric vehicles. The private sector must take this cue to develop sustainable and innovative business models for battery/energy as a service. This opens the possibility to integrate battery infrastructure with renewables, contributing to the growth of the sector, while also mitigating pollution.

The central government’s flagship infrastructure modernisation programme — Gati Shakti — made a prominent mention of clean energy usage, but how this would be integrated into the project is yet unclear. Indeed, the transition to cleaner forms of energy for hard-to-abate sectors like road transport and shipping would signal a paradigm shift right down to the supply chains. The road transport and shipping sectors, and the renewable energy sector have much to gain from this. This is indeed true for the other infrastructure development areas that include railways, airports, and mass urban transport.

The railways have already committed to becoming a net-zero emitter (removing as much carbon from the atmosphere as it generates) by 2030. And several airports have also begun transitioning to solar power.

Missed Opportunities

Given the distress among India’s small business community, one of the ways to attempt accelerated adoption of renewable energy would have been to craft affordable Green Tariffs (GTs) for this sector. Draft rules in this regard have already been circulated among the ministries and are awaiting final approval from relevant authorities. GTs avoid upfront capital costs for MSMEs and other large consumers to install renewable energy infrastructure, while allowing them access to renewable energy. This would have also encouraged renewable energy producers to increase their generation capacities. Initial trends from a WRI-led survey of the MSME sector’s appetite for GTs across five states have revealed considerable interest. But a lack of liquidity, access to finance, limited knowledge of technology trends and their difficulty in identifying competent vendors to install renewable energy infrastructure have stymied the MSME sector’s accelerated adoption of renewables.

This Budget continued to reflect a policy trend of prioritising grid-scale solar. Vast untapped renewables like offshore wind and small wind turbines also provide significant opportunity for India’s clean energy transition and could have been mentioned in the Budget. Also conspicuous by its absence was the announcement of incentives or budgetary allocations to produce green hydrogen. These are despite the government’s own initiative to develop centres of excellence on offshore wind power and an ambitious Green Hydrogen policy.

Concerns That Must Be Addressed

Aside from these direct linkages to the renewables sector, some policies could have indirect consequences for the sector. For instance, the Ken-Betwa river linking project. Aside from the ecological concerns, its proposed renewable energy co-benefits are minimal — 27 MW from solar and 103 MW from hydro. Instead, India could prioritise tapping into the large reserve of roof-top spaces for solar projects across the country. Moreover, rooftop solar projects are not accompanied by conflicts over land rights, migration and rehabilitation needs. These issues have already flared up in Gujarat and Rajasthan where large grid-scale wind and solar projects have come into conflict with conservation and local communities. WRI with partner organisations is conducting research to develop principles and approaches that the renewable energy sector should take, considering ecological, social and human rights aspects while it expands. We believe the renewable energy sector has a terrific opportunity to establish itself as the Responsible Energy sector.

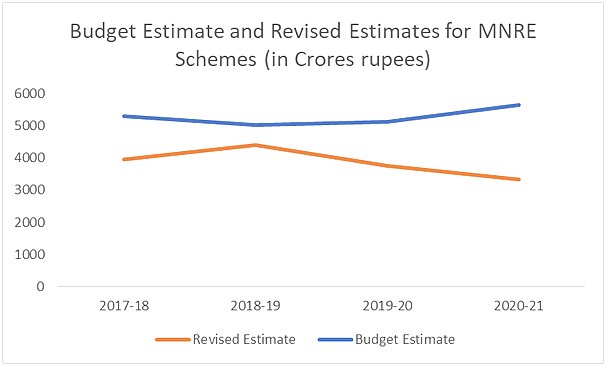

And finally, the government’s expenditures on the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) needs further analysis. A comparison of budgetary allocations and spends by the MNRE over four years reveals consistent under-utilisation of funds. For instance, Budget 2020-21 Budget Expenditure (BE) was Rs 5,646 crore for the Ministry, but the revised expenditure was a mere Rs 3,343 crore. The MNRE is the primary implementing agency for the government’s renewable energy and energy transition projects. We need to understand why there is significant underspending, at a time when renewable energy is expected to become the primary fuel to power India’s economy.

Tirthankar Mandal, Deepak Krishnan, Sandhya Sundararagavan and Kunal Shankar are part of the World Resources Institute, India’s Energy Programme. They work on energy governance, clean energy, energy transition, and communications, respectively. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Read all the Latest Opinions here

Comments

0 comment